Cricket legend Ebony Rainford-Brent: ‘Anyone can suffer from imposter syndrome – it’s part of who we are’

Scouted at 12, part of the World Cup-winning England team and the first woman to commentate on men’s cricket, Ebony Rainford-Brent ‘s life has been marked by incredible success – yet she has experienced imposter syndrome from an early age. Here she shares her story, from her beginnings in cricket and the prejudice she had to overcome, to identifying the thinking that was holding her back, and finding ways to manage it

An esteemed England cricketer, captivating broadcaster and sporting boundary-breaker, Ebony Rainford-Brent has more than made her mark on the sports world. As the first black woman to represent England at cricket, she shattered barriers and paved the way for greater inclusivity in the game. From her first game at primary school to her insightful analysis as an international cricket commentator, she’s become a role model for aspiring players and fans alike.

Her sporting career is packed with personal highlights, but her proudest moment came when she was a member of the England team that won the 2009 Cricket World Cup, then within three months went on to triumph at the final of the Women’s World Twenty20, win the NatWest One Day series and retain the Women’s Ashes. “We were hailed as one of the most successful England women’s cricket teams and cricket teams of all time,” says Ebony. “Being around people who were so laser-focused to achieve that goal taught me so much about life and blew my mind in terms of expectations.”

After retiring from cricket in 2012, Ebony’s infectious enthusiasm for and desire to improve the sport led her to executive posts on several sporting boards, as well as gracing the airwaves as a pundit for the BBC’s Test Match Special and Sky Sports – importantly, becoming one of the first women to commentate on men’s international cricket matches. With such a wealth of experience, talent, and incredible achievements, it’s hard to imagine that Ebony might ever have doubted her abilities, but from a young age she experiences imposter syndrome, and it’s something that still affects her today.

A natural talent

Growing up in Herne Hill, south London and raised by her mum, in her words – as “a typical inner city girl” – Ebony was surrounded by her football-loving brothers and friends. No one she knew played cricket, so the sport wasn’t on her radar at all. That is, until she played her first game at primary school aged nine via the charity Cricket For Change – and it was love at first whack. “I felt such freedom and once I got into competing, I was on the path quite quickly,” Ebony recalls.

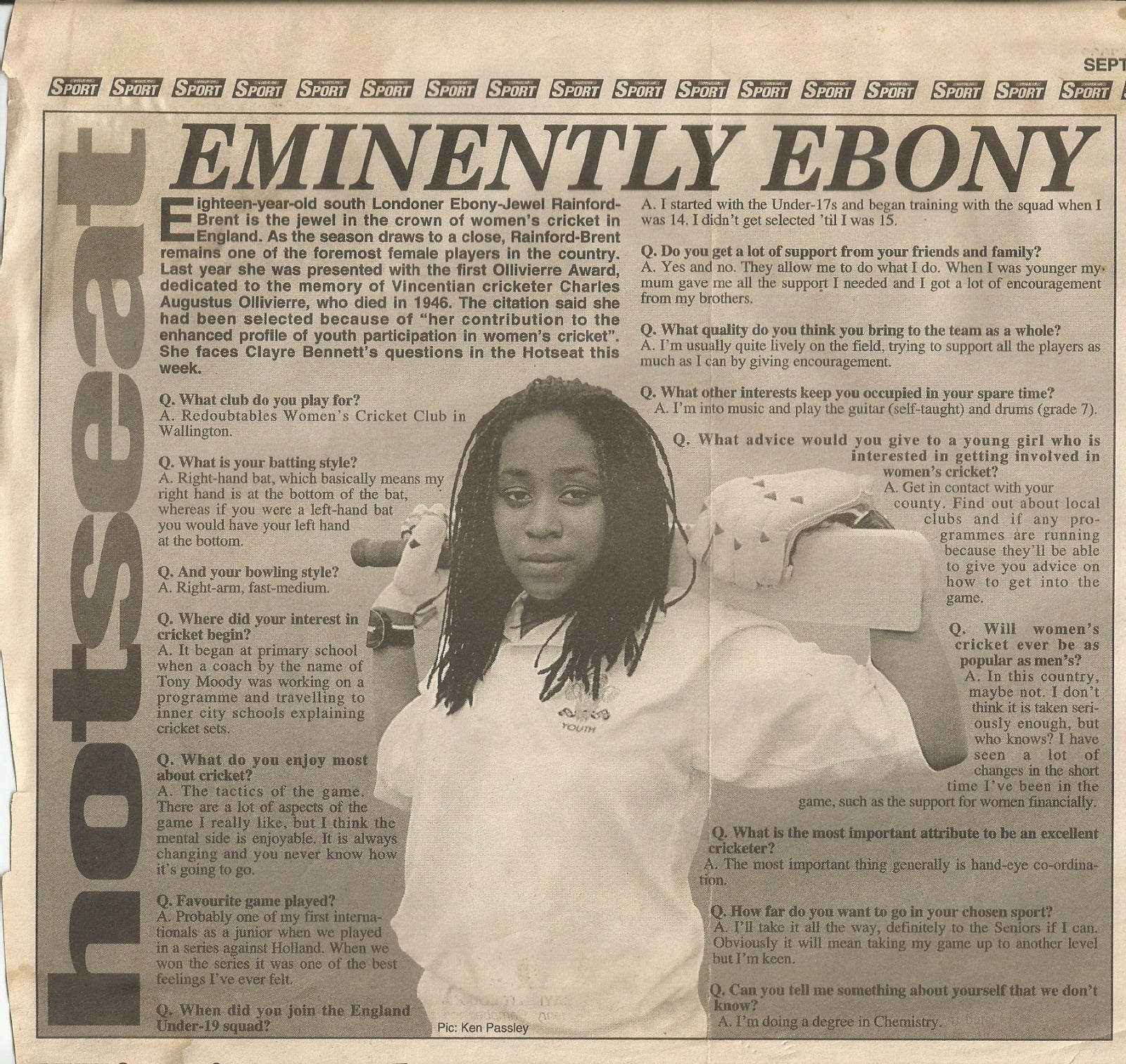

She was scouted to play for Surrey county aged twelve, and remembers her first trial with poignancy. “There’s this photo where all the girls are in pristine white, and I’m in the middle wearing a big baggy red jumper, purple shorts, standing barefoot, with my body language all awkward and off to the side,” she recalls. “I was going into a world where I didn’t feel like I belonged – in so many different ways.”

While most other families drove to games, Ebony and her mum would get two or three buses. She knew she stood out – people sometimes made cruel comments about her background and colour of her skin – and the doubts that she deserved any of her accolades were hard to ignore. When a letter announcing her acceptance into the Junior England team came through the door, Ebony stared at it in disbelief. “It was addressed to me, but I couldn’t believe that could be true,” she says. “‘There’s no other Ebony Jewel Rainford Brent living here!” my mum said at the time – she really had to convince me.”

As she progressed through from the under-11s to the Surrey Women’s senior team and even becoming captain, those feelings of inadequacy and fraudulence prevailed. If someone congratulated her or commented on her performance on the pitch, Ebony would deflect it with a self-deprecating joke and push the focus of conversation onto someone else. “I took in all the negatives and none of the positives,” she says. “I believed the narrative in my head which said that it wasn’t a sport for me, and that I wasn’t good enough to be doing what I was doing.”

While Ebony notes that lots of men experience imposter syndrome, she believes it’s definitely more common and far-reaching among women, especially young women. “For hundreds of years, society has told women what they can and can’t do, and laid on expectations of what they should and shouldn’t be,” she says. “When it comes to cricket boards, I’m often the only woman in the room, and I’m looking around thinking, ‘Do I belong here? How do I communicate? Should I speak their language or can I speak my own?’”

While Ebony is pleased to see more workplaces improving their culture and enabling more women to progress in the professional sphere, she’s realistic about the added pressure and expectations women face after hundreds of years of historical biases. Instead of trying to ‘fix’ imposter syndrome though, Ebony herself has found that the best path forward is to accept it as a normal part of being human. “It can happen to everyone – a person who’s super confident and sure in one area can feel it when they try something new,” she says.

When she has done corporate public speaking and opened up about her imposter syndrome, she’s been amazed to hear so much of the audience share their own experiences too. Some might be able to overcome it entirely, while others can be content with improving responses over time. “Even if we just exist with imposter syndrome, that’s okay,” she says. “Instead of purging ourselves of it, we need to understand imposter syndrome – it’s just part of who we are and how we operate.”

Opening up

To better understand her own imposter syndrome, Ebony uses journaling. Every morning, she asks herself two key questions – what she’s thinking, and whether this should be accepted as a truth. She becomes a judge and jury – separating the judging imposter syndrome, from evidence that counters it. “Questions like: ‘Have I done the work I should have done?’ help to change my thinking around imposter syndrome,” she explains. “The thoughts might still be there, but I question the negative biases, and don’t fall into it accepting them point blank.”

This system of reflection through writing enables her to work through emotions and step outside of them. “Be silent with yourself and reflect, before sounding it out with one or two good people you can trust, whether that’s a family member, mentor or coach,” she explains. “Bounce it off others and they will reflect it to show up your biases which should help you see that you’re doing the work, you deserve your success, and you do belong.”

That said, Ebony has also learnt from being too trusting and vulnerable in sharing with others. “At times, I’ve felt insecure and scared to open up, then have done so to someone who wasn’t necessarily in my corner, wasn’t empathetic or who brushed me off, which made me feel worse,” she says. “Find someone who you trust who believes in you and your capabilities – test the waters, open up a little and begin to build that relationship.”

To help her get out of her own head and speak her imposter feelings out loud, Ebony leans on her mum and an external coach, who she has been seeing every fortnight for two years. “It helps to have someone who doesn’t know my background, and provides total honesty and objectivity,” she says. Without these strategies, Ebony doesn’t think she would have been able to manage the imposter syndrome throughout her career. The combination of journaling and talking authentically about her feelings has helped shift her mindset. “Doing so will help break the cycle of being in our heads, or going into a negative spiral,” she says. “It’s simply a way of asking better questions and reflecting to change our own perspectives of ourselves.”

Even with all the right tools, Ebony’s relationship with imposter syndrome fluctuates. Her early days of commentating were fraught with doubt and worry, which was only compounded by the social media reactions after each TV appearance. “Before I only had to contend with my own judgement of myself, but with Twitter and all those people saying what they thought about me in public, I started questioning whether I was good enough,” she says. “Suddenly I was getting comments like “You’re a woman, get back in the kitchen” or “You’re only there because you’re a token seat”. Before games, Ebony would have vivid nightmares that someone was going to drag her off air.

To cope, she learnt to dissociate her worth from social media narratives. Other commentators reminded her to back herself and ask those important questions. “Things like ‘Have you done your research?’ ‘Do you know the players?’ ‘Have you said what you wanted to say?’” she says. “They told me if I had done all those things, I shouldn’t be worrying about what the world says.” They’re rules she still leans on today – Ebony will be presenting at the Ashes 2023 soon and has resolved not to look at Twitter for the first week of the tournament. “I’m going to get myself into the flow without worrying about what others think,” she says.

Whether she’s tackling new sporting challenges as non-executive director of the England and Wales Cricket Board (ECB) or helping others as the chair The African-Caribbean Engagement Programme, Ebony accepts that imposter syndrome will continue to crop up, but she’s unfazed.

In fact, moving past the idea of confidence is something Ebony sees as key in tackling these feelings. “If we only do things when we feel confident, we often don’t take action that will help us,” she says. Instead, she encourages young women to feel courage. “Confidence is overrated - I’d like young women to work towards a mindset where they don’t always have to feel empowered and at the top of their game to feel they can do something. When you’re feeling hesitant, flex that muscle to say “Okay, I’m not feeling confident right now, but I’m going to put myself forward or give that a try anyway. You’ll be amazed by what you achieve.”

Galaxy® is committed to help one million people, including women, their families and communities thrive by 2030 via its ‘Your Pleasure Has Promise’ manifesto and vital initiatives including the Women for Change programme in collaboration with CARE and their How to Thrive series in partnership with Young Women’s Trust. Click here to find out more