Voyager spacecraft find entirely new ‘unique physics’ outside the solar system

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The Voyager probes have detected an entirely new kind of electron burst outside the solar system.

It is the first time this "unique physics" have been detected by a spacecraft, and could allow for new breakthroughs in our understanding of the "interstellar medium", or the space between the stars.

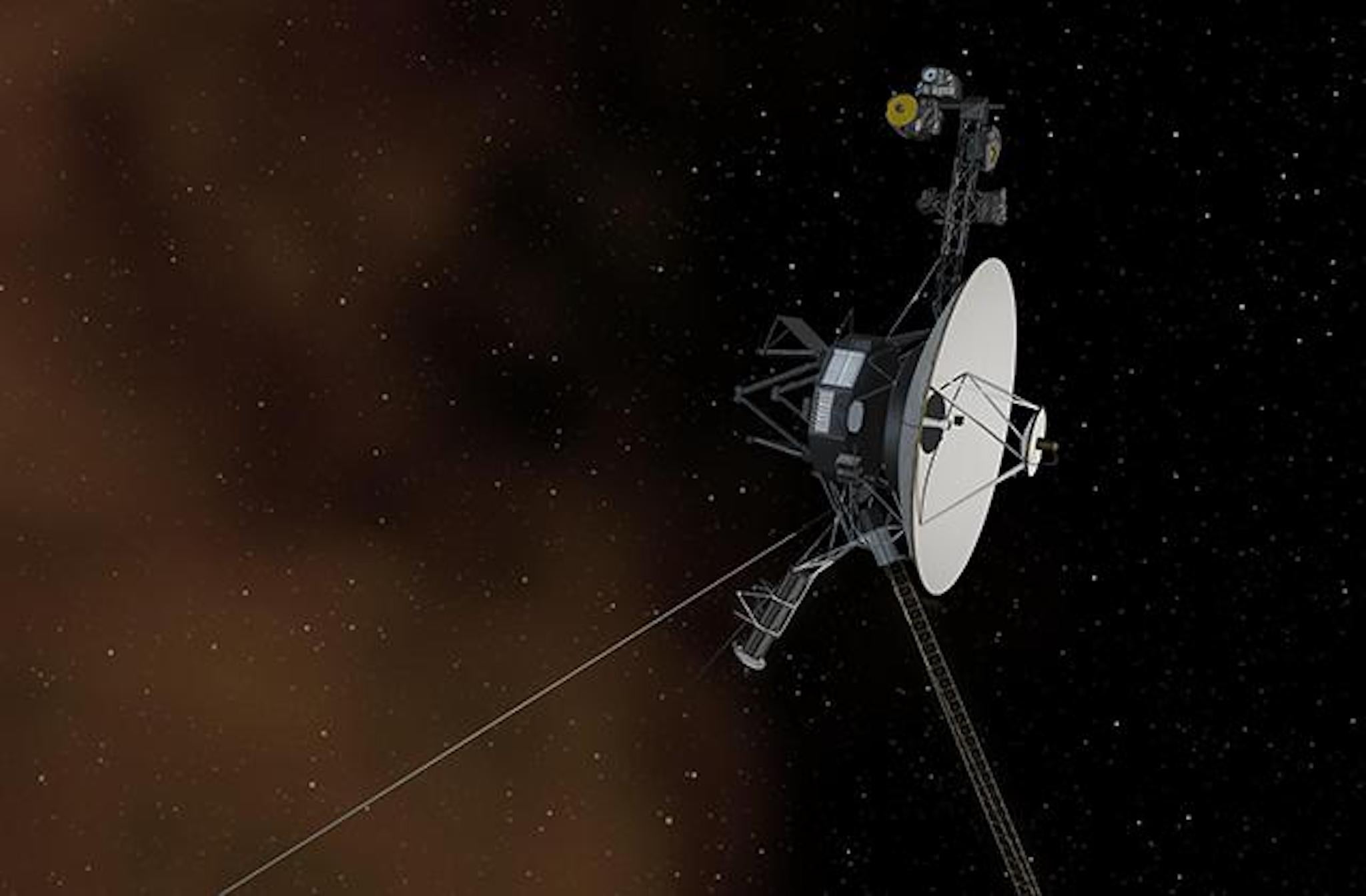

The two Voyager spacecraft were launched by Nasa more than 40 years ago, with the aim of flying to the far reaches of our solar system. They have now gone even further than that, reaching interstellar space, and exploring the gaps between the stars, giving us the first glimpses of what it might be like in that mysterious zone.

The latest discovery from the spacecraft – using data taken from both Voyager 1 and 2 – saw them pick up bursts of electrons like none ever detected before. They found that cosmic ray electrons are being accelerated by shock waves that originate in major eruptions on the sun, and are then flung out into space.

The electron bursts travel ahead of the shock waves that throw them out into space. The electrons travel at nearly the speed of light, accelerating along magnetic field lines.

Soon after, the lower-energy electrons arrive, sometimes taking days to do so. Then the shock waves themselves are detected by the spacecraft, sometimes as much as a month later.

The shock waves themselves come from coronal mass ejections, which are clumps of hot gas and energy that are thrown out of the Sun at roughly a million miles an hour. The Voyager spacecraft are now so far away what even at that speed they take a year to be detected.

"What we see here specifically is a certain mechanism whereby when the shock wave first contacts the interstellar magnetic field lines passing through the spacecraft, it reflects and accelerates some of the cosmic ray electrons," says Don Gurnett, professor emeritus in physics and astronomy at Iowa and the study's corresponding author.

"We have identified through the cosmic ray instruments these are electrons that were reflected and accelerated by interstellar shocks propagating outward from energetic solar events at the sun. That is a new mechanism."

Scientists now hope they can use this discovery to better understand both the shock waves and the radiation itself.

That in turn could help inform considerations when sending astronauts on long missions to the Moon or Mars, since they will be exposed to far more cosmic rays than we would on Earth.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments