The ENIAC machine: Rhodri Marsden's Interesting Objects No.100

The first electronic general-purpose computer's main job was to make ballistics calculations

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The front-page headline in The New York Times this weekend in 1946 turned out to be rather an understatement: "Electronic Computer Flashes Answers, May Speed Engineering". It referred to ENIAC, the first electronic general-purpose computer, whose 18,000 vacuum tubes and towering operational panels had just been unveiled in Philadelphia. Built for $500,000 (£4.2m today), ENIAC's main job was to make ballistics calculations (or as the newspaper obliquely put it, "a very difficult wartime problem") which had hitherto been done by an army of mathematicians. At ENIACs unveiling, one of the machine's developers, Herman Goldstine, spoke of the "mountainous computational burden" they had carried.

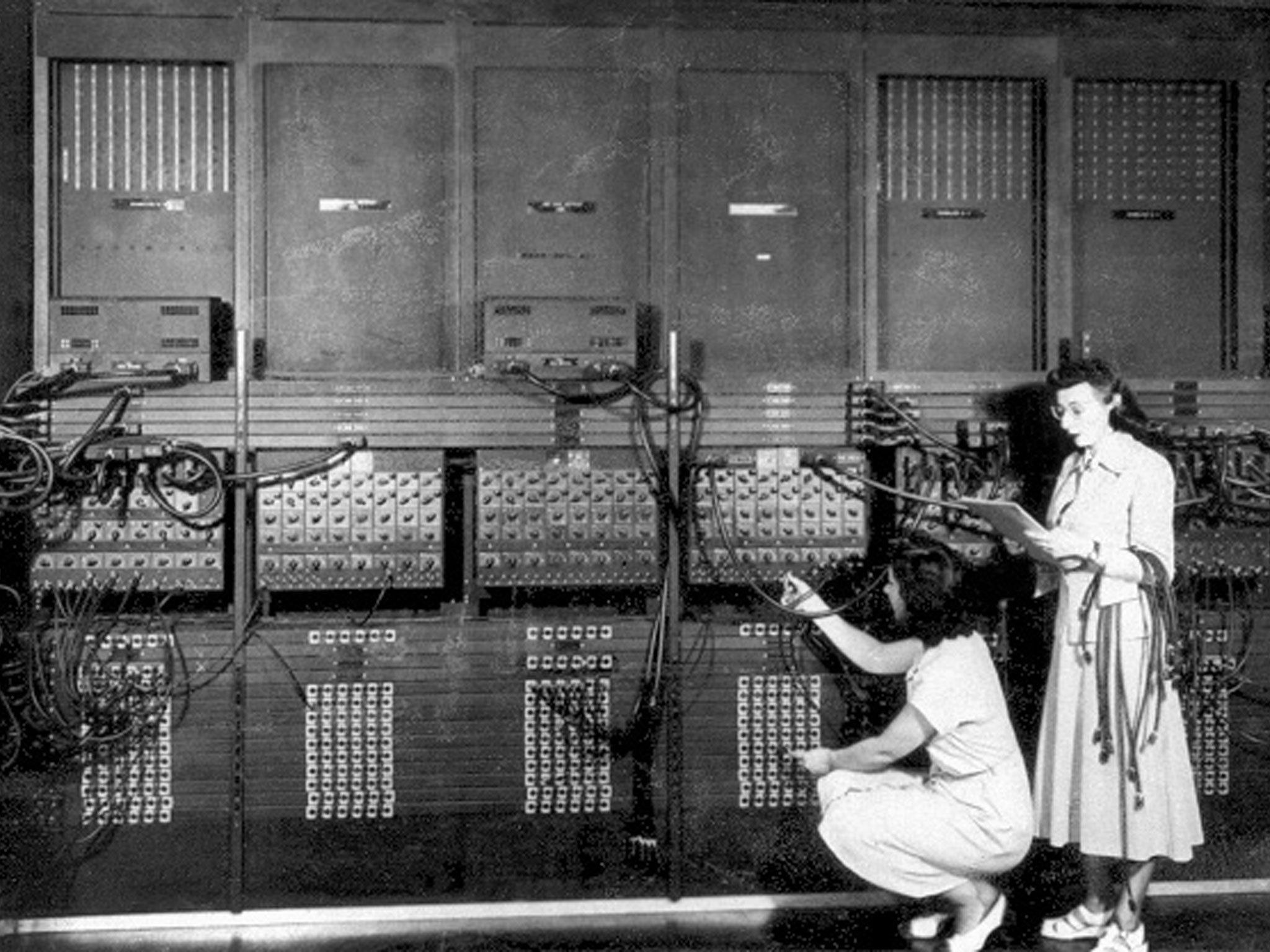

Six of those mathematicians can occasionally be seen in the photographs taken on ENIAC's launch day, but none of them was mentioned by name. While the computer hardware was built by men, the machine was programmed entirely by women, namely Kay McNulty, Betty Jennings, Betty Snyder, Marlyn Wescoff, Fran Bilas and Ruth Lichterman. As if their task wasn't hard enough (no computer language, no operating system) they weren't actually allowed to see the highly classified, 30-tonne machine; they were given logistical diagrams of its 40 panels and told to get on with it.

"It was fabulous," recalled Jennings many years later. "ENIAC calculated the trajectory faster than it took the bullet to travel." The women, known as "Computers", had done a magnificent job, but their work wasn't properly recognised until quite recently. A 2013 documentary was made to honour them by lawyer and programmer Kathy Kleiman, who recalled asking a computer historian who the women in the ENIAC photos were. He guessed that they might be "models to make the machines look good". They were actually the world's first professional computer programmers.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments