Nasa finds ‘surprising’ signals of subsurface lakes in Mars areas too cold for liquid water

‘We’re not certain whether these signals are liquid water or not, but they appear to be much more widespread’

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Nasa scientists have found “surprising” signals suggesting the presence of lakes below the surface of Mars, despite being in areas that should be too cold for water to remain liquid.

According to the researchers, including Jeffrey Plaut from Nasa’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), and a team from the Italian Space Agency, radar signals reflected off the Red Planet’s south pole in a 2018 study appeared to reveal a liquid subsurface lake in the Martian region.

Further research, including a new study published by the same scientists in the journalGeophysical Research Letters, also describes finding dozens of similar radar reflections around the south pole, suggesting the presence of subsurface lakes in frigid areas of the Red Planet that should be too cold for liquid water.

“We’re not certain whether these signals are liquid water or not, but they appear to be much more widespread than what the original [2018] paper found,” Plaut said in a statement.

“Either liquid water is common beneath Mars’ south pole or these signals are indicative of something else,” he added.

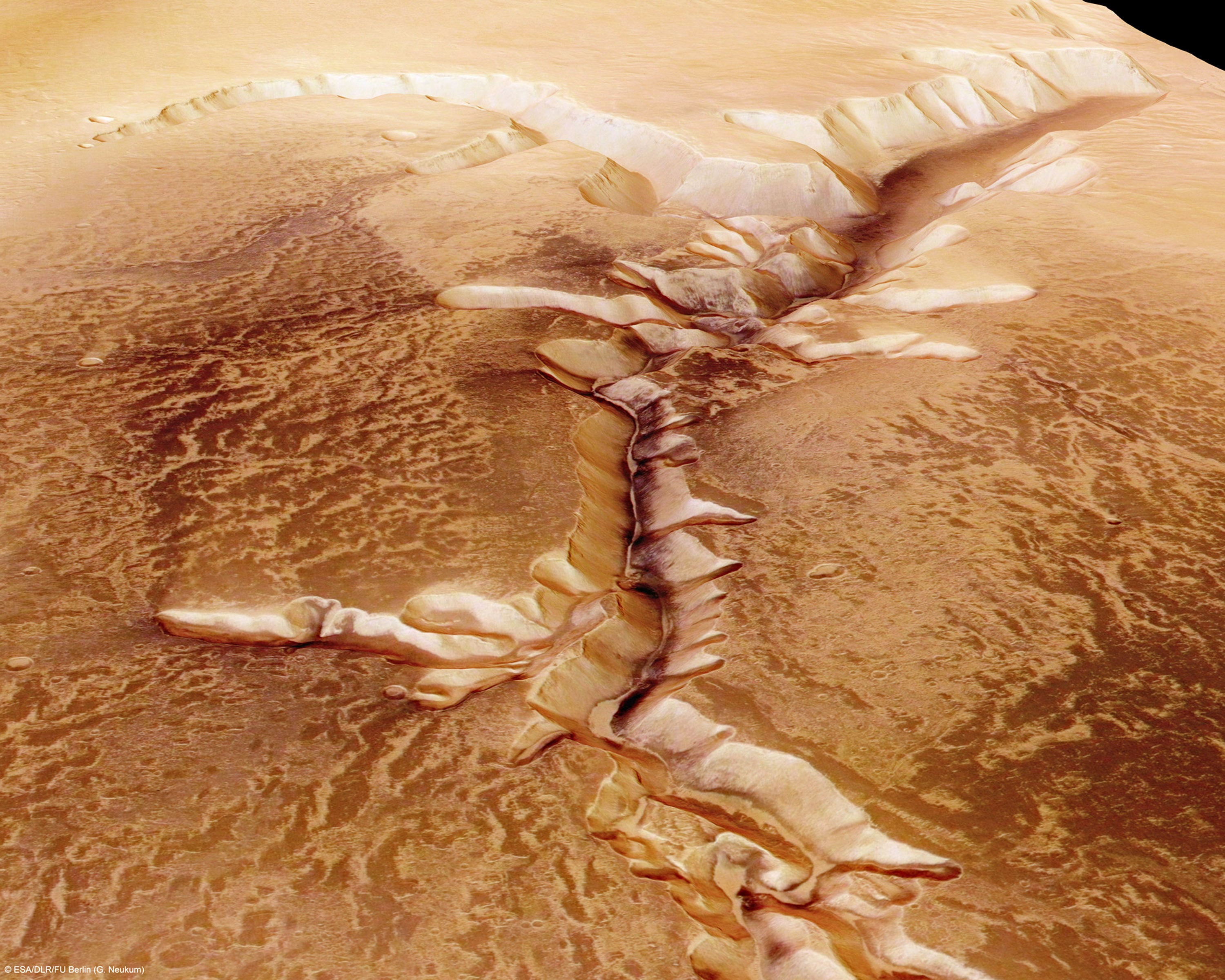

This region of Mars, known as the South Polar Layered Deposits, is named for the alternating layers of water ice, dry ice (frozen carbon dioxide), and dust that have settled there over millions of years.

By beaming radio waves at the surface and studying the reflections, the scientists say these icy layers can be mapped in detail.

While radio waves usually lose energy when they pass through material, and have a weaker signal when they bounce back from a surface, the researchers say the waves from this region’s subsurface were brighter than those at the surface.

They said that this could point to the presence of liquid water, which strongly reflects radio waves, but added that this conclusion cannot be made for sure.

These puzzling radar reflections came back from areas that include those less than a mile below the surface, with freezing temperatures of -63C.

They believe recent volcanic activity under the surface could be one explanation for the potential presence of liquid water under the Martian south pole.

“One possible way to get this amount of heat is through volcanism. However, we haven’t really seen any strong evidence for recent volcanism at the south pole, so it seems unlikely that volcanic activity would allow subsurface liquid water to be present throughout this region,” study co-author Aditya Khuller from Arizona State University said in a statement.

While the study could not conclude whether there are subsurface lakes in the region, the scientists believe the findings offer a detailed map of the Martian south pole with clues to the Red Planet’s climate history.

“Our mapping gets us a few steps closer to understanding both the extent and the cause of these puzzling radar reflections,” Plaut added.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments