The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Samsung Galaxy Fold: How the strange new bendy phone was born

'We have been solving those challenges one by one'

First, it was just a rumour. Then, it was shown off in the dark, all shadows and mystery. Now, we've seen it – though very few people have still ever touched it.

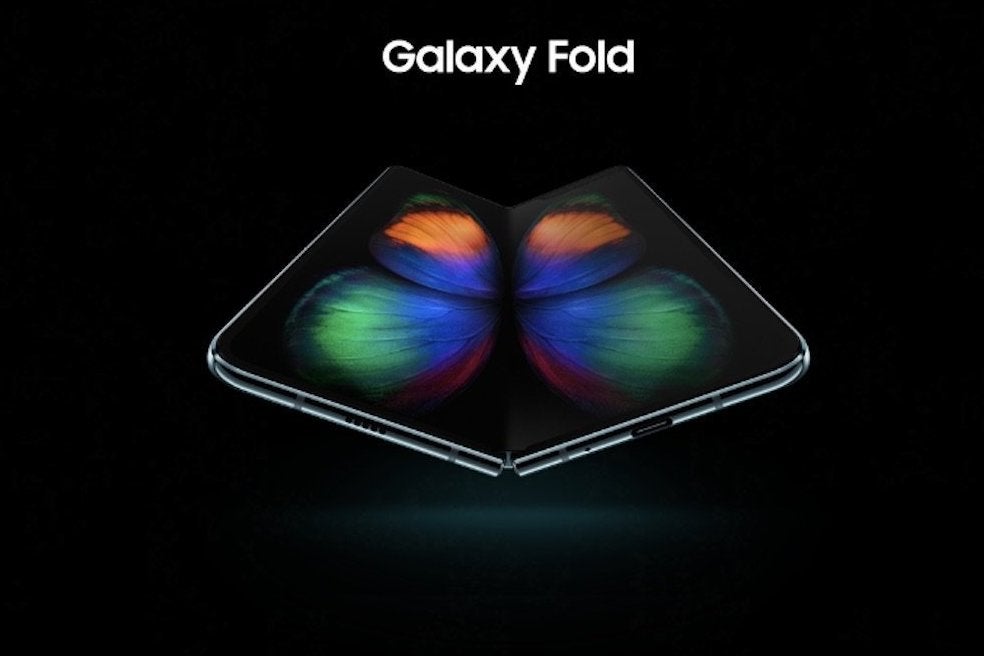

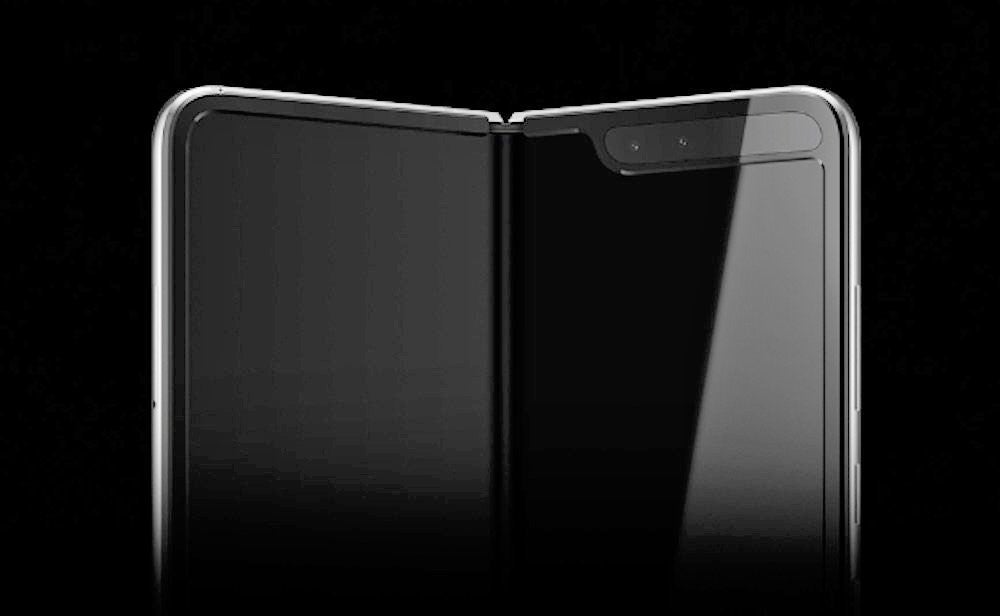

Samsung's bendy phone – which folds in the middle, allowing it to be thin and long like a folded sheet of paper, or open up into a big tablet-size device – was the first among a category that seems already to be expanding into the new big thing in handsets. Named the Galaxy Fold, Samsung's new model costs £2,000 and is a big bet for the company.

It is a category around which there is a thrilling combination of intrigue, excitement and concern. But it is the first time in years there has been such an innovation in the smartphone market, where the products have been largely just getting thinner and faster for years.

Instead, it is a truly new category. Whether or not it takes off, it is seizing on technology that has never been seen before in a phone – features like bendy screens and special hinges that have hardly been seen in consumer products at all.

But if that innovation was ever going to make sense, the software underpinning it had to be just as innovative – and perhaps more smart. ES Chung, as Samsung's executive vice president and head of software and AI, has led the building of the software that works as glue to hold this ambitious and strange project together.

That has involved creating entirely new features – not just software tweaks, but entire new kinds of infrastructure to power the complex system of two display.

"For example, we have a feature we call app continuity," says Chung. It means that "you can just open" the screen which works as a full-fledged display.

"If you want to go big screen you can just open it, and the app you're running on the front cover continues to work in a bigger screen," he says. "So it's a very seamless transition from closed to open form factor."

That is the same version of the app: whatever you're doing on the small screen will still be happening on the big screen, just now in an expanded form.

If that's not enough, however, the large inside screen is flexible in more ways than one. The bigger display will allow you to open up to three applications at the same time.

"Say you are doing some gaming – so you have your gaming app in our main screen, and at the same time you want to chat with your buddies while playing the game." The Fold's display can support all that – plus another, if you want, such as a YouTube stream or some music.

Even if the phone can handle that much multitasking, many of its users won't. But Chung points out that there are plenty of more productive uses, too: you might want to have your email open in one display, messages in another and music in the third for instance, and people can do all of that in a "very smooth way".

All of that happens on a screen that is much more square than you might expect – at first glance, it looks square, though Chung explains that it is actually four to three, in line with a traditional PC display. That allows for plenty of space for multitasking and documents, he notes, though it will also support videos in whatever aspect ratio it wants.

The first question that anyone tends to ask when confronted with a foldable phone is: why? The second one is often: why now?

But Chung explains that it is not quite as immediate as it might appear. The foldable phone has been in the works almost since the beginning of the modern smartphone era, ushered in with the Galaxy S series and the iPhone.

"We have been doing this research for around eight years: it didn't happen overnight," he says. "We saw the need for this kind of form factor, but then there are a lot of technical challenges.

"So we have been solving those challenges one by one," he says, noting that as well as the more obvious hardware questions posed by a foldable phone, there are plenty of software ones too.

"We really wanted to bring our very nice software experience," he says. "We worked very closely with Google on that because we didn't want to create a proprietary solution only for Samsung devices."

That meant digging down into the guts of Android, ensuring that features like app continuity and three multitasking windows that all work together could be supported by an operating system that was built for simple smartphones, not bendy modern mobiles.

It was important to make sure that foundation in place because it would be disastrous if developers came to the phone and found that the new environment – two screens, one bendy – broke whatever app you had worked so hard on, and which users wanted. "So we really worked closely with Google so maintained a framework of support to keep your app still running," he says – "as an app developer you don't have to worry that you are running on a Fold".

As well as the developers of the infrastructure with Google, Samsung also says it worked hard with the developers who build on that infrastructure: companies like Facebook and Instagram, who will be creating the tools for this new device. "We know this is not a one player game," says Chung, noting that it was important to address the entire ecosystem of content providers and app developers.

All of that can sound painfully complex: it can be difficult enough to keep up with how a one-display phone works, in an era of constant software updates and alterations, let alone one with two displays and a whole array of displays. But Chung insists that the foundations and basics of the phone will be familiar, even if its form is very strange.

"The front screen is just like any regular Android phone," he notes – and then opening up the phone means doing that same thing, but now bigger.

"You don't have to do anything special as a user: you just open it, and then we will make sure that the same app will continue on the main screen, with more space."

Once you're in that big screen, the phone can be used as a tablet, or with a few simple gestures the multitasking and other features can be introduced. That should avoid the fear of a big learning curve and added complexity as you try and use the phone, he says.

Behind the scenes, of course, more complex processes are going on. But it is based on largely the same principles: you are running an app on the phone's small screen, and then when the display is opened it will detect that event, telling the phone to switch displays and show the app in its big screen mode. It is genuinely the same app, meaning that you should be exactly where you were when you were using it in small screen mode.

"Everything happens behind the scenes," he says, meaning as a user "you don't have to worry about that". Switching should be "pretty instant", and there should be "no kind of interruption" as you do so, since everything has been built to work together.

Now that the phone is on its way out to the public, Chung suggests that its future will largely be decided by the people using it. The Fold has been built to allow it to embrace the various ways people are going to use it – ways that Samsung is aware it might not yet have thought of.

All of that work done with Google and other content providers and developers should make it easier to build apps that take advantage of the extra space, he says.

All the same, Samsung doesn't want to "burden the developer", by forcing them to create two versions of every piece of software. Instead, "the system should do all the work for the developers", allowing them "not to worry about it". They can just focus on developing the application – which will then be able to pop out or not, depending on where it and its user are.

That is a philosophical as well as a technical commitment: the point of the changing apps is that, when they're opened up on the folding screen, they're just the same app but bigger. Even today, when having two displays means having two different devices, apps are largely thought of as continuous, and an app on a tablet is an extension of the one on the phone. The same principle applies to the Fold, says Chung, with apps not showing in two different versions so much as in two different sizes.

Chung is speaking during MWC in Barcelona, where the entire phone industry descends for a week in March to announce their latest phones; while we talk, people are elsewhere admiring folding phones from other companies like Huawei. A year ago, bendy handsets seemed impossible, but now they're impossible to avoid.

He says this sudden flourishing is helpful for Samsung and everyone else involved in the market, since the more companies showing them off the better acquainted people will be with them.

The same thing happened with big phones – then known as phablets – that were pioneered with devices like the Note.

Just like with the foldable phones, those handsets were beset by doubt. Initial versions of those phones had problems with their screens, and questions over how exactly they would be used; nobody really knew what they were, whether they were a phone or a tablet, and it eventually became clear the answer was actually sort of both. There were fears they would cannibalise each other, as the phablet made both a phone and a tablet redundant.

Now the same questions are now being raised over the Fold. Chung hopes the answers will be the same, too – that the phones will find their own place in the market and create something new, not kill something old.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks