Philae comet lander could be about to die during most dangerous part of Rosetta mission

The Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko comet is at the point closest to the sun that it will be, known as the perihelion

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The Philae lander’s mission could come to an end as scientists have warned that the comet it is attached to is undergoing the most dangerous part of its mission through space.

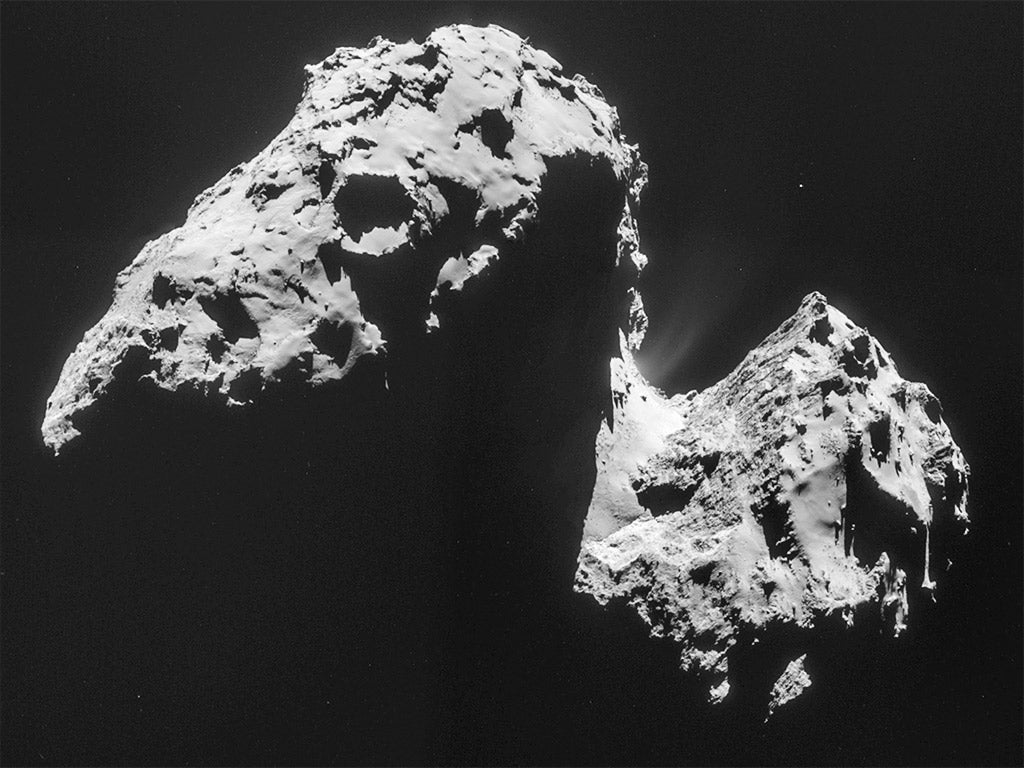

Gerasimenko reached perihelion, its closest point to the sun, today. A host of jets of gas and dust have been thrown out of the comet, which could throw Philae off into space, or it could break up entirely.

An expert said that there was a roughly 20 per cent chance that the comet would break-up, but that it was unlikely to happen during the mission.

Philae dropped onto the comet on November 12, when it started examining its new home. It hasn’t been heard from since July 9, and scientists are now anxious to see what will happen to it during the difficult period.

"Obviously the activity is dangerous for Philae,” said Philae operations engineer Barbara Cozzoni. "First, the dust can prevent Philae collecting energy. And Philae is not anchored, so it might change the attitude of Philae — but we don't think it's going to send it into space."

The Rosetta orbiter, which flies around the comet to support the Philae lander during its mission, has been moved away from the comet to ensure its safety. It is now sitting 327-kilometers from the comet.

Measurements by the Rosetta orbiter suggest that up to 300 kilograms of water vapour - equivalent to two filled bath tubs - are spewing out of the comet every second. This is 1,000 times more water than was observed a year ago when the spacecraft first approached the comet.

The comet is also thought to be shedding up to 1,000 kilograms of dust per second, threatening to cloud Rosetta's sensitive instruments and obscure its star tracking navigation equipment.

Scientists revealed that yesterday Rosetta's Osiris scientific camera took dramatic images of a second powerful outburst from 67P's larger lobe.

The first occurred on July 29 when bright jet of gas and dust was seen erupting from the comet's neck region at between 10 and 30 metres per second.

Activity is expected to increase even further over the next few weeks as the sun's "thermal pulse" works its way through the comet.

Osiris principal investigator Dr Holger Sierks said there was a strong likelihood of the comet breaking in half, but not just yet.

A fracture 500 metres long and up to 2.4 metres wide has been observed crossing the comet's neck.

Asked about the possibility of Rosetta witnessing the comet splitting in two, Dr Sierks said: "Let me phrase it this way: I think there are good chances it will break up, but not in this orbit. The probability of it breaking up is in the region of 20%. But the chances it will break up while we are there are very minute."

Currently the fracture is in shadow and Rosetta too far away to photograph it.

"We will see it again in spring next year, and then we'll compare before and after to see how the crack has changed," Dr Sierks added.

Additional reporting by Press Association

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments