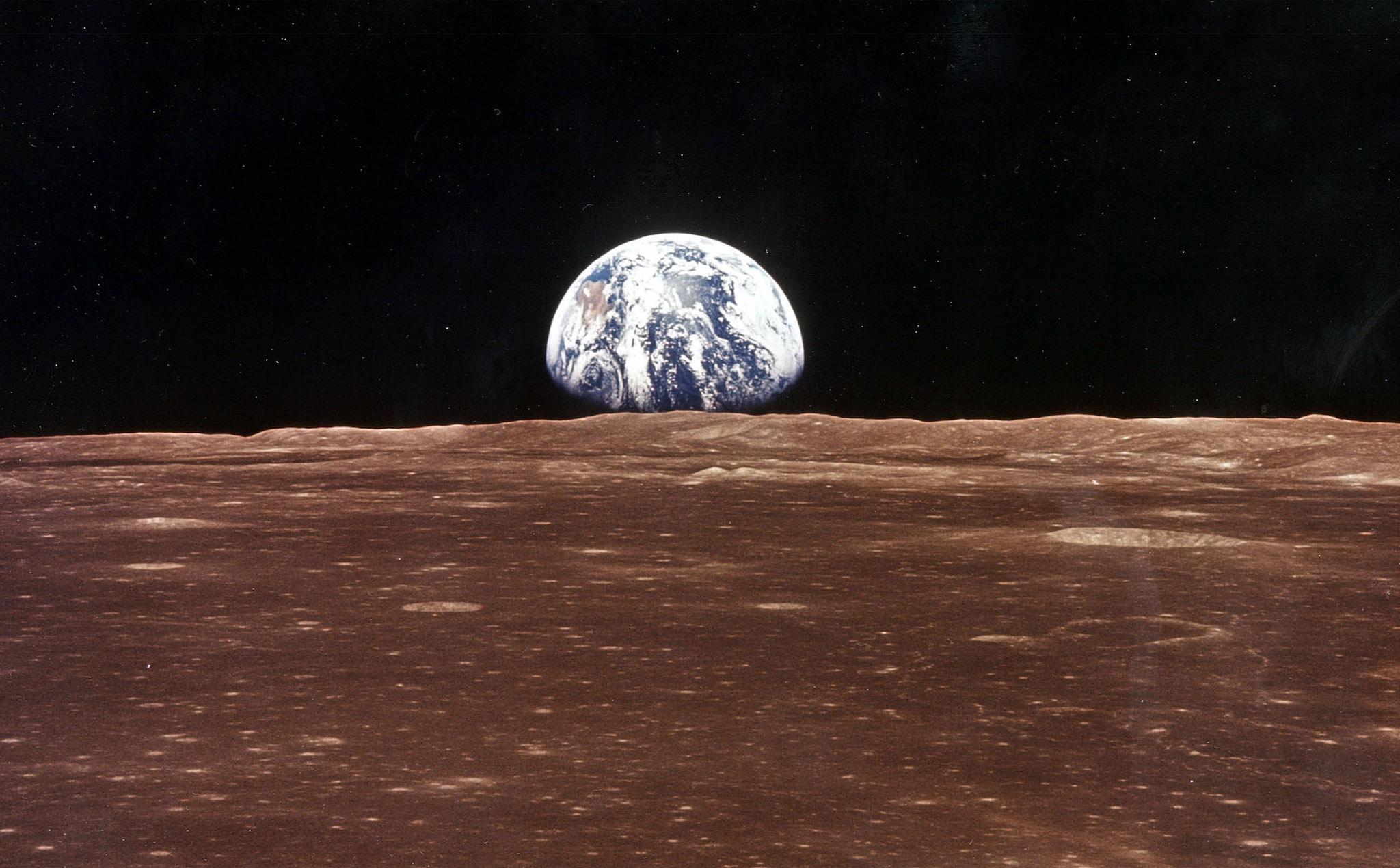

The Moon is more metal than we thought, scientists say

Findings from Nasa orbiter could challenge our understanding of the Moon's formation

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The Moon is more metal than we thought, scientists have said.

The discovery could challenge our understanding of how it was formed, the researchers claim, after discovering new information from data sent back by a Nasa craft sent to visit the Moon.

For a long time, scientists have debated how the Moon was formed. The most popular story suggests that it was created after an object the size of Mars hit the Earth, sending what is now the Moon off into orbit.

But the subsurface of the Moon is more rich in metals than previously thought, suggesting that may not be true.

The researchers made the discovery after taking radar imagery of the ifne dust at the bottom of craters on the Moon. They did so using an instrument on board the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, which is in orbit around the Moon so that it can study its surface.

They found that the dust appeared to suggest that the subsurface of the Moon is richer in metals than previously believed.

It appears that the fine dust might actually be materials which have been thrown up from below the Moon's surface, after it was hit by meteors. The deeper craters appeared to have more metal in than the ones that were more shallow, allowing researchers to infer that might be the case underneath the surface, too.

Scientists have already struggled to account for the fact that the Moon has a higher concentration of iron oxides than the Earth does. The new study suggests that difference could be even greater than previously thought, deepening the mystery of how the discrepancy – and the Moon itself – came about.

It may be possible than the collision that formed the Moon was more dramatic and devestating than previous thought, and so sent pieces from deeper within the Earth than expected; it may also have happened when the Earth was younger and covered in a magma ocean.

"By improving our understanding of how much metal the Moon's subsurface actually has, scientists can constrain the ambiguities about how it has formed, how it is evolving and how it is contributing to maintaining habitability on Earth," said Essam Heggy, research scientist of electrical and computer engineering at the USC Viterbi School of Engineering, who led the study.

"Our solar system alone has over 200 moons - understanding the crucial role these moons play in the formation and evolution of the planets they orbit can give us deeper insights into how and where life conditions outside Earth might form and what it might look like."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments