Challenger disaster: How a TV critic described the explosion 30 years ago

'We may not be able to believe that something truly terrible has happened anymore unless we see it six or seven times'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.As the space shuttle Challenger roared away from Earth on 28 January 1986, only CNN was covering it live for a national audience.

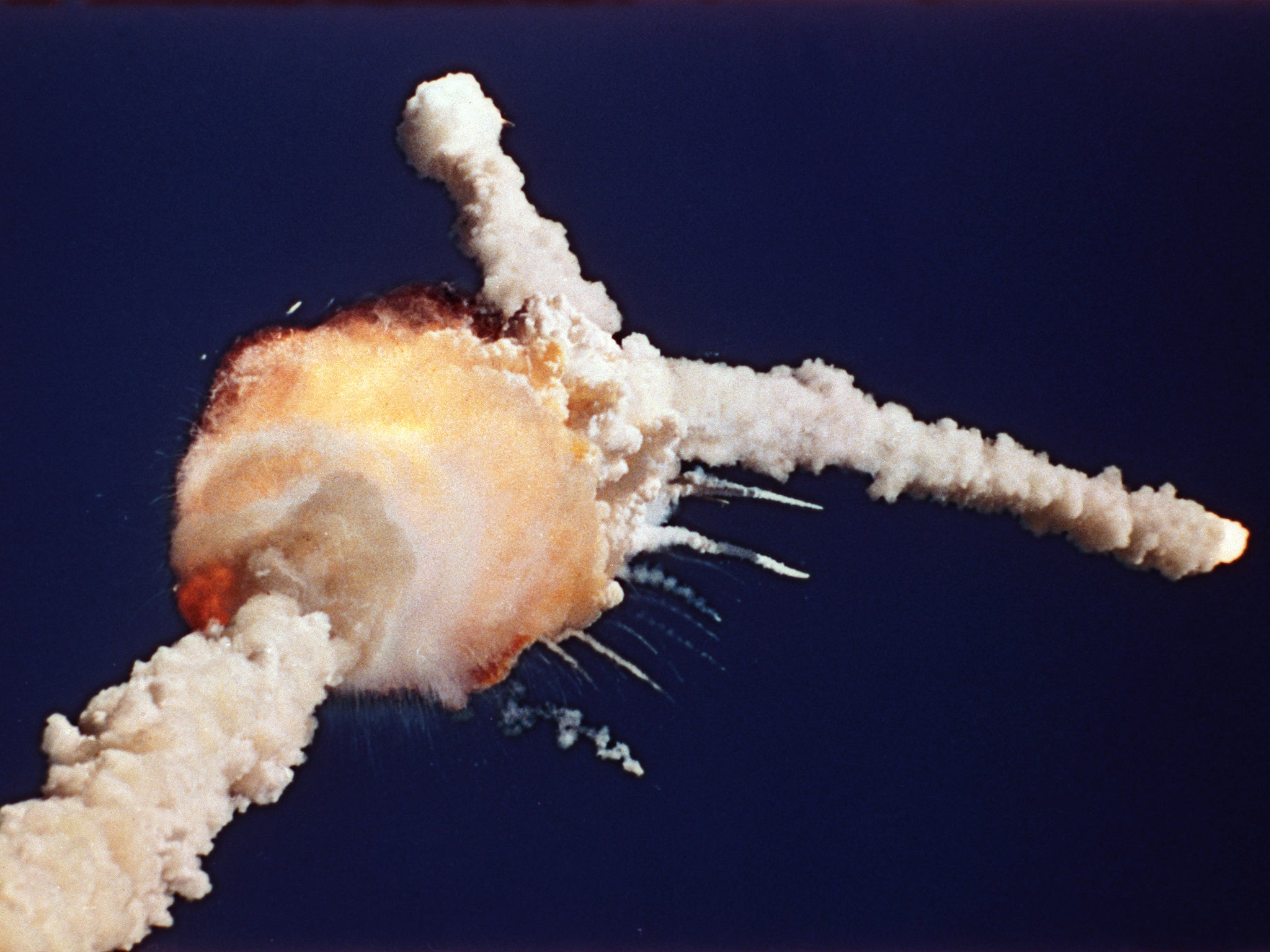

For 73 seconds, viewers saw only the orbiter and its rocket boosters, the orange tail beneath, the blue sky above. Then came the upward cascade of smoke and fire, the comets of debris. The narration from NASA droned on for a few more moments (“One minute 15 seconds, velocity 2,900 feet per second…”) — but soon came the muffled cries of alarm, then the low thunder of the explosion.

In the next day’s newspaper, Washington Post TV critic Tom Shales wrote about the experience of watching the doomed launch — over and over — as the networks began their rolling coverage.

Check out his first line: It perfectly prophesied the 21st century’s obsession with replay and looping of major disasters, and our new rituals of public grief on social media.

Horror of the fire in the sky: Cruel visions, over and over, bring the nightmare home

By Tom Shales

Washington Post Staff Writer

Jan. 29, 1986

We may not be able to believe that something truly terrible has happened anymore unless we see it six or seven times on television. Yesterday, something truly terrible happened, the explosion soon after liftoff of the space shuttle Challenger, and the three networks, each sustaining marathon coverage during most of the day, played, replayed and re-replayed videotaped footage, sometimes in slow-motion, sometimes frame by agonizing frame, of this truly terrible occurrence.

Maybe on the 10th or 20th replay, you think as you watch, it won’t happen. Maybe this time the shuttle will continue its upward climb and not disappear in a cloudy ball of fire. As NBC News anchor Tom Brokaw said late in the day, looking back at the hour when the story first broke, “We were all suspended for a time between a state of belief and disbelief.” Finally, belief takes over.

For several hours, the networks dropped all commercials, concentrating exclusively on coverage, as they did in 1963 when President Kennedy was assassinated. Network anchors, during prolonged crises like this, aren’t there just to impart or repeat information; they become, in a sense, national hand holders, figures of supportive strength. None was stronger yesterday nor more supportive than Dan Rather of CBS News, who logged 5 1⁄2 continuous hours on the air, starting at 11:45 a.m. when he went on live from a “flash studio,” reserved for bulletin news, off the CBS news room in New York.

Without makeup, without even his contact lenses at first, Rather seemed initially disoriented and harried, which was the way a viewer felt upon learning that a launch of the space shuttle, now such casual features of the American landscape that the networks no longer carry them live (only the Cable News Network aired the launch live yesterday), had gone horribly awry.

All three network anchors rose to the occasion and performed admirably over long stretches of time, mobilizing vast communications technologies to communicate a great breakdown in technology. Brokaw, who had been attending a White House briefing on the State of the Union message when the news from Cape Canaveral came in, rushed back to NBC’s Washington studios and was on the air at 12:11 p.m. ABC’s Peter Jennings somewhat awkwardly joined, then later replaced, morning anchor Steve Bell at 12:04.

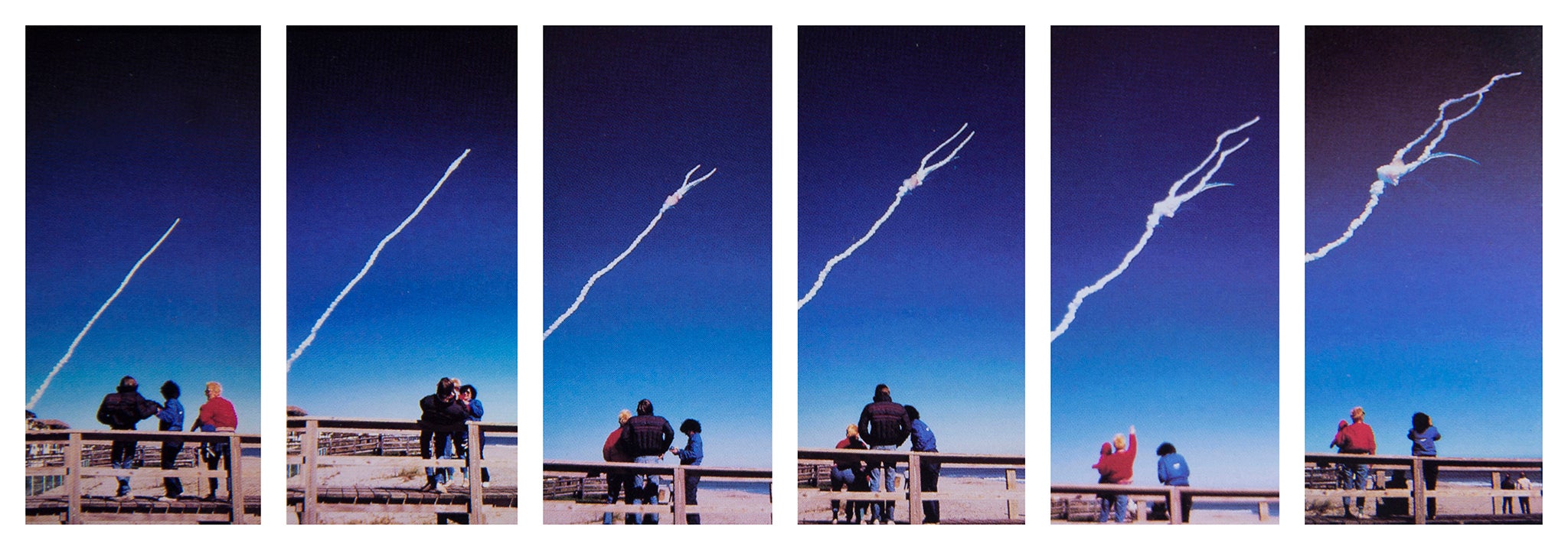

The footage of the explosion was played by each network too many times to count. But there was other footage, just as cruel, including shots of observers watching at Cape Canaveral as the mission ended in nightmare. Among them were the parents of Christa McAuliffe of Concord, N.H., the brave civilian who was to become the first “teacher in space.” We watched as members of her family learned what we already knew. We were all joined in being stunned together.

McAuliffe was the crew member of whom the general public was most likely to be aware, although the crew seemed a remarkable cross section: another woman astronaut, a black astronaut, a Hawaiian astronaut and a civilian businessman, among the others. The thing that seemed to make the story most painful as the day went on was the presence of the teacher.

By virtue of having been selected for the mission, McAuliffe became Everyteacher, a symbol of a profession whose business, after all, is the future. You may have felt as you watched that this was not only Ms. McAuliffe on board. She was Miss Murdock who taught you multiplication tables in the third grade. She was Mrs. Petersen, who taught you not to split infinitives. She was Mr. Alft, who thrilled you with a meaning of the Bill of Rights. No wonder we sat there absolutely devastated by the news that television was obliged to bring us.

It is part of the new video reality that when almost anyone celebrated dies, we see soon afterward crisp taped footage of that person alive and vibrant, which is how McAuliffe and astronaut Judy Resnik and the others on board looked yesterday when the footage was played on the air in memoriam. A camera had been stationed in Concord to record the reaction of high school students there as they watched the launch and as, heartbreakingly, their giddy high spirits turned to surpassing sorrow. They sat there in party hats looking anguished and betrayed. On a day like this, America is a small town, a community of grief, and it rallies around television to give it not only news but hope. Network news anchors and correspondents, among the most frequently criticized of all public professionals, performed superbly yesterday.

In the scramble to cover the tragedy, each network showed some evidence of resourcefulness on the air. NBC News brought in a child psychologist to advise parents on how they might help children adjust to the traumatic news of the day. ABC had former astronaut Gene Cernan live from Houston to narrate slow-motion replays of the explosion and explain as much as possible what might have caused it. CBS had test pilot Leo Krupp brought in for the same chore.

“The CBS Morning News” was already in Miami Beach for a week of special broadcasts from that city. After yesterday’s broadcast, which ended before the launch, anchors Forrest Sawyer and Maria Shriver and five vans full of equipment were transported to the cape for today’s follow-up coverage, with all previously planned segments of the program scrubbed for now. All three networks planned late prime-time reports on the explosion last night, and ABC News expanded “Nightline” to an hour.

Not every word or gesture was well-considered during the coverage. ABC News correspondent Lynn Sherr, at the jet propulsion lab in Pasadena, Calif., for coverage of the Voyager 2 Uranus probe, appeared incongruously jolly and smiley on the air. A sour wrong note. Jennings kept talking during live coverage of reaction from former space traveler Sen. Jake Garn (R-Utah), telling viewers “we don’t need to hear him” to know what he was saying; but then Jennings stopped talking and we did hear him. Brokaw may have been out in left field when he speculated that critics of President Reagan’s Strategic Defense Initiative project would use the shuttle calamity as evidence of “just how wrong things can go in space.” Rather, alerting viewers to the upcoming statement from the White House, said “President Nixon” would be making it, then quickly corrected himself.

Earlier, though, Rather more than once achieved the kind of common-man eloquence that makes him not only a valued source of information at a time like this, but a valued companion, someone of authority and yet camaraderie. At one point, he quoted what he said was an old sailor’s expression: “Thy sea is so great, and my boat so small.” He later read a poem by a former astronaut over footage of the Challenger crew on tape, preparing for the voyage that would end in a holocaust.

The profile of the crisis seemed somehow classic, reminiscent of the convulsive day in 1981 when Reagan was the victim of an assassination attempt. First came the initial shock of the news. Then the event was replayed over and over until it penetrated the national consciousness, rising in impact with each replay until, inevitably, it reached a point of diminishing returns. Then word came from the White House that the president’s State of the Union address, contrary to official pronouncements of only moments earlier, would be postponed, so profound seemed the effect of the tragedy on the viewing nation. Perhaps the fact that all three networks stayed on the air with the story instead of returning to regular programming had an added impact on the White House decision. “The president,” said Larry Speakes, “like everyone else, watched this on television.”

By midafternoon, disc jockeys, at least one in Los Angeles, were dedicating songs to the memory of those who died in the crash. Some local stations, on their evening newscasts, were including stories about how Americans watched the crisis on TV. Very quickly, television reorders American life and creates American lore.

Senator and former astronaut John Glenn, interviewed in Washington, said, “This is a day we’ve managed to avoid for a quarter of a century . . . we hoped we could push this day back forever.” Second-day coverage today, the aftermath phase of the disaster, may see a good many news people chasing astronaut families — particularly the family, friends and students of Christa McAuliffe — for tearful sound bites to be played and replayed on newscasts to come. But yesterday, during yet another long vigil before the set, the networks acted admirably and with distinction. President Reagan said, “Today is a day for mourning and remembering,” but it was also, of course, a day for watching, and for not wanting to believe what one saw.

© Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments