8 men and women once sealed themselves inside fake Mars colony for 2 years — here's what it's like today

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A decade before Elon Musk founded his fast-rising rocket company, SpaceX, or spoke publicly about colonizing Mars, a different billionaire captivated the world with Biosphere 2.

Ed Bass, an oil tycoon, spent about £183 million to build and operate that facility as a proof-of-concept for a permanent, self-sustaining habitat on Mars. Four men and four women sealed themselves inside the airtight space in September 1991 and emerged two years later.

The experimental space-age facility served as the stage for a spectacular and controversial story of human endurance.

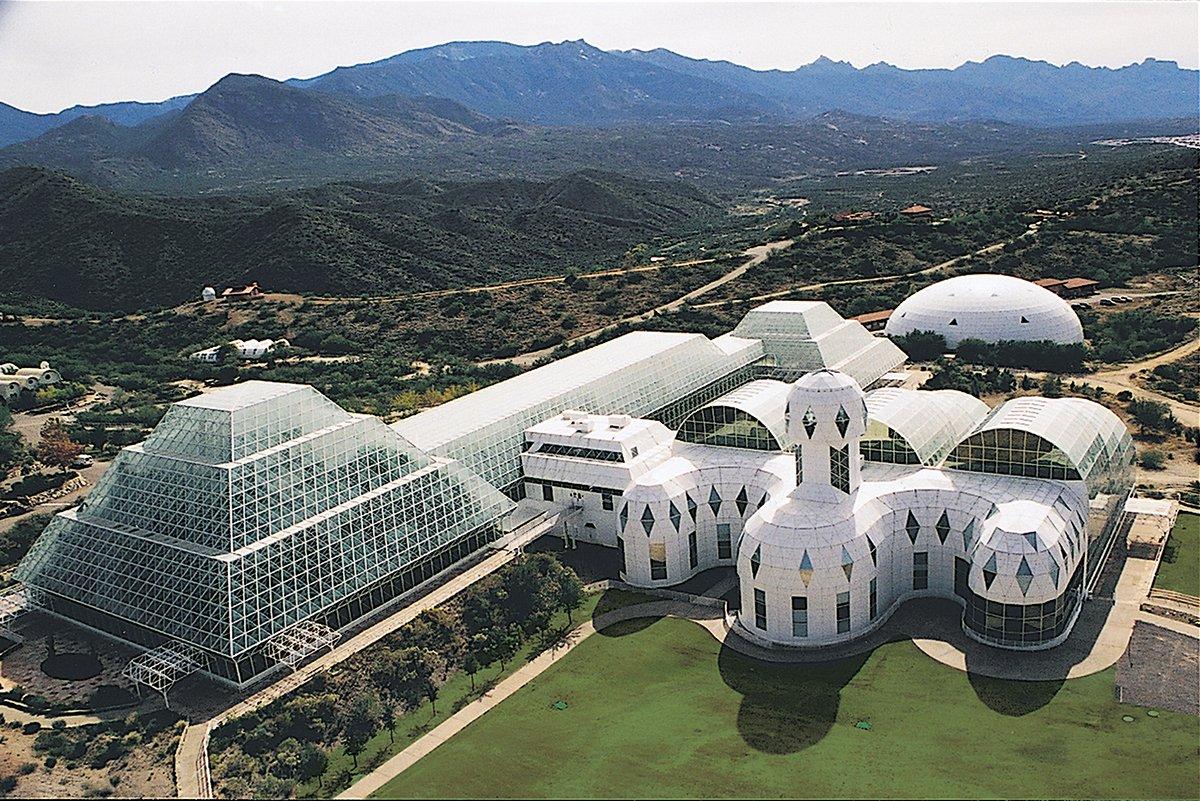

Built into a hillside of the Arizona desert during the early 1990s, the complex remains a functional marvel of engineering.

Here's what it's like inside the 3.14-acre bubble today.

Biosphere 2 is nestled in the foothills of the Santa Catalina Mountains in Oracle, Arizona. The area is part of the Sonoran Desert — an arid, unforgiving, and eerily Mars-like region that stretches from western Mexico into the US Southwest.

The architect Peter Pearce created Biosphere 2's space-age frame out of 77,000 steel struts and 6,600 silicon-lined glass panes to trap air inside. It can even withstand orange-size hail, which pummels Arizona about once every century.

The first crew (there were two) walked through a modified submarine bulkhead on September 26, 1991, and sealed the airlock behind them. They wouldn't leave for two years. That entryway is where tours begin today.

The tour guide of this particular visit was John Adams, the facility's deputy director. Adams, who has worked there since the mid-1990s, is an expert on its complex systems, science, and history.

"It really showed us how little we truly understand Earth systems and how infinitely complex they are," Adams said of the first Biosphere 2 closure experiment. "There were a lot of people who said, 'You bottle this up, you close it up, it's just going to turn into a big ball of slime.'"

It didn't, and the eight crew members emerged alive — though they wound up needing some outside assistance.

When the first crew of "biospherians" settled inside the complex, it trapped 7.2 million cubic feet of air — yet leaked only the equivalent of a thumb-size hole.

Though the facility was once a privately funded experiment in human survival, the University of Arizona bought it in 2011. It's now a scientific research facility, conference centre, and tourist attraction.

Biosphere 2 has seen about 3 million tourists and 500,000 students since 1991. The site also contains a village where visiting researchers can stay. It's quiet out there in the desert, save for the wailing of coyotes at dusk.

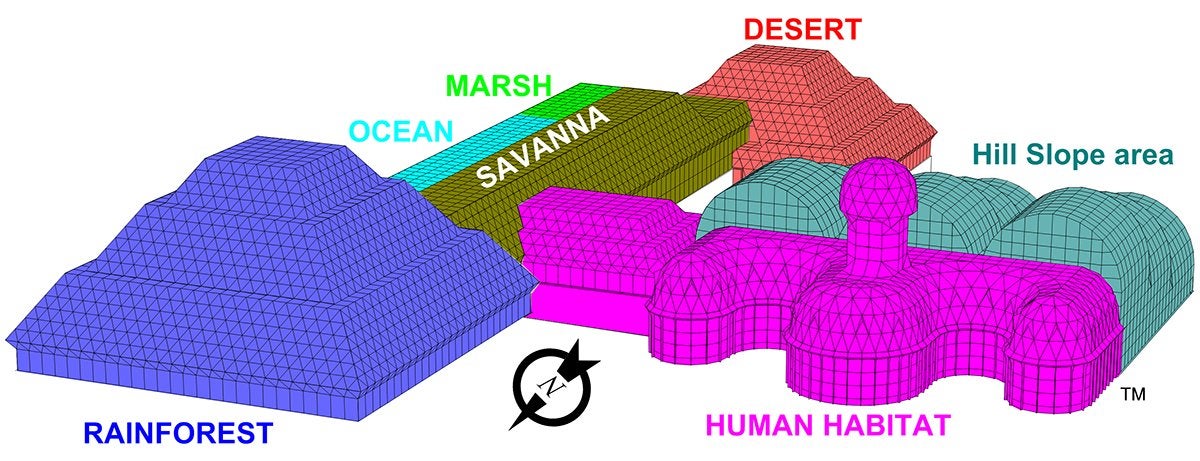

Inside Biosphere 2, five "wilderness" zones — rainforest, ocean, savanna, marsh, and desert — emulated Earth's ecosystems. They helped scrub carbon dioxide from the air and generated oxygen. The crew lived in a connected habitat and farmed crops in an agriculture zone that's now called the hill slope.

In that intensive agriculture zone, shown here in 1993, crew members spent most of their 12-hour days toiling in the fields and animal pens to harvest enough calories.

The kitchen was hallowed ground. Biospherians ate only what they could grow — mostly sweet potatoes and beans. It took four months to harvest enough ingredients to cook a pizza. Animals had to be raised and slaughtered to get meat. Coffee was a twice-monthly luxury.

Biospherians kept detailed records of seeds, plants, food, and animals. About 20% of species inside — mostly insects that were out-competed by cockroaches and crazy ants — went extinct during the first two-year experiment. Today, a small fraction of the original species survives.

Crops no longer grow in the hill slope. Instead, the University of Arizona has renovated it into a multimillion-dollar experiment called the Landscape Evolution Observatory.

LEO uses 90-foot-long bins of crushed volcanic rock to study how microbes transform inhospitable grit into environments where plants can take root.

The goal is to understand how climate change will transform formerly arid regions as they're doused with rain from new weather patterns. Hundreds of sensors and sampling tubes embedded in the bins give scientists a 3D view of the evolving soil. The work may one day come in handy for Martian farmers.

The most iconic areas of Biosphere 2, however, are its wilderness biomes. The air still smells of wet soil and plants, and though it's no longer sealed, it is noticeably more humid in here.

The "ocean" holds about 660,000 gallons of saltwater and undulates with the help of a large wave generator.

The ocean, one of the largest contained saltwater research facilities in the world, is being renovated to study coral bleaching, a scary consequence of climate change.

Next to the ocean is the rainforest biome.

It's a thick, steamy jungle choked with tropical vines and trees.

Visitors aren't typically allowed into the rainforest area beyond a viewing point, but Adams escorted us around.

Biospherians treasured the bananas it grew for them. The sweet fruit was so versatile and prized in meal-making — and snacking — that it had to be locked in a room while it ripened.

Many of the crew members sought out the rainforest's diverse ecosystems and soothing waterfalls for an escape. Today, it's an active research facility used to study tropical drought due to climate change, as well as the cornucopia of compounds emitted by plants.

After a trek through the rainforest, Adams walked us through the savanna, which connects the ocean, rainforest, marsh, and desert biomes.

Plants of all shapes and sizes fill the savanna. During the first experiment, it also harbored a troop of four galagos, or nocturnal bush babies, that served as primate companions to the biospherians.

The desert biome at the end of the savanna encapsulates the environment that's right outside.

Biospherians spent a lot of time weeding the region, since winter condensation on the roof dripped into the soil, growing plants that should have been dormant.

The complex's steel struts not only support the facility's glass panes, Adams explained, but also serve as a way to scale the walls for harvesting, measurement, cleaning, repairs and more. For fun, some biospherians even climbed to the ceiling and dove into Biosphere 2's ocean.

Today, a few biospherian living quarters are roped-off museum exhibits showcasing some belongings of the crew members of second mission's crew. (Because of financial and legal issues, it lasted only seven months, in 1994.)

A small science museum set up in Biosphere 2's former control room shows off a prototype for establishing a self-sustaining base on the moon or Mars.

That concept, called the Prototype Lunar Greenhouse, consists of sealed tubes intended to supply 100% of the oxygen and 50% of the food a person needs in space.

The tubes are designed to pop out and assemble within 10 minutes.

A central module could deploy a dozen greenhouse tubes to keep a small crew alive for two years. This technology could buy crucial time for astronauts to establish a permanent settlement on the moon or Mars. But NASA's funding for the project recently ran dry.

Around the corner from the museum is a staircase leading to the habitat's towering library.

The library offered biospherians a refuge from the cameras of a never-ending stream of tourists and press. This area, which still has the original and distinctive purple carpeting, is now off-limits to visitors.

Underneath Biosphere 2 is secret underworld of vital human machinery: the Technosphere.

The Technosphere is a maze of pipes, tubes, conduits, pumps, sprinklers, transformers, air handlers, and other parts required to keep air, water, and electricity flowing through the complex.

As biospherians would discover, concrete that lined the facility's base was soaking up carbon dioxide. Soil microbes were gobbling up oxygen, turning it into carbon dioxide, and trapping it the concrete — away from plants that could turn it back into oxygen.

This led oxygen levels to drop to the equivalent of the peak of a 15,000-foot mountain. To fix the problem, biospherians tried to collect every scrap of organic matter, dry it out in the Technosphere, and halt its decay.

But the design flaw proved too great. Mission managers eventually wheeled 14 metric tons of liquid oxygen through an airlock to make up for the lost gas.

That procedure was performed in one of two domed buildings called "lungs," which helped control Biosphere 2's air pressure and prevent outside air from leaking in. Without them, air that warmed during the day would have expanded and blown out panes of glass, ruining the experiment.

The lungs are remarkable feats of engineering. A giant suspended weight creates a slight pressure that ensures air is pushed out of any leaks in Biosphere 2, not sucked in. A fan above the weight moves it upward during the day as temperatures (and air pressures) rise to prevent glass-pane blowouts.

To show how the lungs work, Adams opened a nearby airlock. The lung's weight immediately descended, forcing a blast of air through the unsealed door.

With my tour complete, I exited through the gift shop. On display was a book by Jane Poynter, one of the original crew members.

The book is one of the most detailed and candid accounts of Biosphere 2's genesis, construction, goals, and problems.

It's also an insider's account of a plethora of human and scientific controversies that haunt the project's reputation to this day — including a remarkable story involving sabotage, federal agents, and Steve Bannon, the former White House chief strategist.

Poynter eventually married Taber MacCallum, a fellow biospherian. "It was an incredibly audacious and, in so many ways, incredibly successful attempt at building a prototype space base," Poynter said of Biosphere 2.

Together, they started a high-altitude-balloon company called World View.

Some scientists today view the experiment with skepticism and describe its founding staff as "cultish," a description Poynter vehemently rejects. Barring a few design flaws, she said, Biosphere 2 showed that people could survive for years without much — if any — outside help.

Getting to Mars is the easy part — the success or failure of a colony will depend on its resiliency and life-support systems. Elon Musk is targeting a first SpaceX crewed mission in 2024, but it remains to be seen how anyone would survive.

"First we need to understand Earth's systems — we need to understand how we're going thrive here on Earth," Adams said. "We have not figured this out yet."

Read more:

• Fifteen sentences your interviewer does not want to hear

• I flew 16 hours nonstop on one of the world's busiest international routes in economy class — here's what it was like

• 16 skills that are hard to learn but will pay off forever

Read the original article on Business Insider UK. © 2018. Follow Business Insider UK on Twitter.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments