Red Redemption 2 plot review: What worked and what didn't in the game's vast story

Now the dust has settled in the streets of Saint Denis, we look back at some of the key points in the game's narrative

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.N.B. This article discusses Red Dead Redemption 2’s plot. As such, there are MAJOR SPOILERS, and if you have yet to complete all of the game’s chapters we strongly recommend you click away now.

Spanning 2,000 pages of script and 500,000 lines of dialogue, Red Dead Redemption II represents a future for the dwindling Great American Novel. Like the very best pieces of literature, RDR2 is greater than the sum of its parts, its impact impossible to trace to a specific plot strand. By the end of the game, the twists of the story dissipate and you are left simply with a feeling; a deep, profound feeling, the shape and character of which you can’t quite explain.

With the game having now been out for over a month, let’s begin unpacking its vast story and the many risks Rockstar Games took along the way:

Arthur’s tuberculosis

For me, it hit after a run-of-the-mill trip to the barbers. I mounted my horse only to keel over and crash to the ground moments later. Having Arthur fall ill off-mission was a stroke of genius, a moment as unexpected and unsettling as the Murfree Brood sneaking up on your makeshift campsite in the woods.

Playing a video game with your playable character terminally ill was a very weird experience. We’re used to missions where you’re either stripped of all your weapons or you’re intoxicated or infected, but they tend to be fleeting. Such a large part of RDR2 was spent sick, though, and Arthur contracting TB proved the turning point in the game. Unfortunately, I think it demotivated me somewhat – gave me less desire to upholster a campsite chair or craft fancy garments when they were to clothe an increasingly gaunt, dying man – but on the whole, I think the tuberculosis arc worked.

Arthur’s death and the transition to John Marston

This was actually a rare case where learning a spoiler only made the experience more moving. I foolishly Googled “RDR2 TB cure”, hoping there was a side-mission I could trigger that would stop Arthur spluttering all over Pearson’s stew. Alas, of course, I learned he was doomed. I imagine most gamers assumed Arthur would recover (especially given the cruel hints of a possible remedy from the Native American tribe), with the gut punch that he would die from the illness only coming very late on. Instead, I spent session after session after session watching this man slowly die before me, knowing his friendship/relationship with Charlotte had no future and that he would never live to see that bizarre mail order wildlife art exhibition he’d been working on.

Arthur’s death gave the game weight and allowed it to bounce back with a more hopeful ending. I loved the guy, but killing him off was the right way to go (even if forcing him to watch his beloved horse croak not long before he did yanked the heartstrings a little too hard).

The transition over to John Marston's POV I was less convinced by. John’s character felt underdeveloped when it came, and I say that as someone who played the first game (I imagine a few people who hadn’t must have been thinking “why the hell am I this guy now?) The whole notion of John’s escape with his family was seeded a little too late, for me, and I felt closer to Charles, or even Lenny just from that one rager in Valentine, than I did to John.

John’s epilogue

Though I didn’t warm to John the way I did to Arthur (the guy just didn’t seem to have a personality), I was completely on board with the house-building epilogue. I’m sure it bored more trigger happy gamers senseless, but for someone who found camp life the most compelling aspect of the game, it was goddamn beautiful watching John, Charles and Uncle build a home. I only wish it had been parcelled out more slowly (fun though that montage was). I would happily have foregone a good 50 per cent of the Pronghorn Ranch section if it meant more time building Beecher’s Hope. This was the pay-off for the game after all, the semblance of the American Dream that Arthur died securing for John.

It also felt like a bit of a missed opportunity not adding a long list of ranch improvements after the credits rolled. I appreciate that they didn’t want to turn this into The Sims: Hey There Mister!, but there would have been a simple beauty to adding new buildings to the ranch, new types of cattle, produce etc., which could have worked much as they did with Pearson’s camp requests.

Part of me also wanted a little more Arthur in the epilogue. A simple burial in a sunny spot on the ranch perhaps, or more discussion of his life between John, Charles and Uncle. Players will track down the remaining legendary animals, cigarette cards etc. just for the sake of getting to 100 per cent completion, but these items could have been tied into the narrative, John feeling a responsibility to settle Arthur’s unfinished business.

This is nitpicking, though, and John’s ranch was a beautiful way to end a story about a group of people so adrift in life precisely because they didn’t have a home.

The pacing

Red Dead Redemption II had two very distinct halves, which can broadly be described as before and after sh*t hits the fan. I remember being surprised how relatively peril-free the game felt during the Horseshoe Overlook and Clemens Point eras, only to miss their simplicity when the Van der Linde gang started to disintegrate thereafter.

There’s usually a slow improvement in circumstance in video game narratives, that runs in parallel with your character’s increasingly improved abilities. Rockstar cleverly exploited this, preying on the pride you felt toward the steadily growing camp as it yanked the rug from under you with the community's collapse. I think I still had one upgrade to source for Pearson when he up and fled Beaver Hollow.

This all served to tie the player to the plot: this was your hard work that Dutch was undoing. Had RDR2 ended with Arthur’s death, I probably would have felt cheated, but the epilogue worked nicely in bringing the game full circle and back to the bucolic atmosphere of Horseshoe Overlook.

The increasingly poor choices of Dutch van der Linde

RDR2 wouldn’t be half the game it is if Micah had been the sole antagonist. He was in fact pretty stock – a rat hiding in plain sight – whereas Dutch’s arc was more subtle. If the game was in part about the American Dream being a lie, Dutch was the snake oil salesman pushing it. I liked how he preyed upon the group’s hope, my only gripe being that I think some members of the gang would have twigged that he didn’t have their best interests at heart sooner. Shooting Micah certainly wasn’t enough to redeem Dutch for me, though it seemed to be for John.

The camp focus

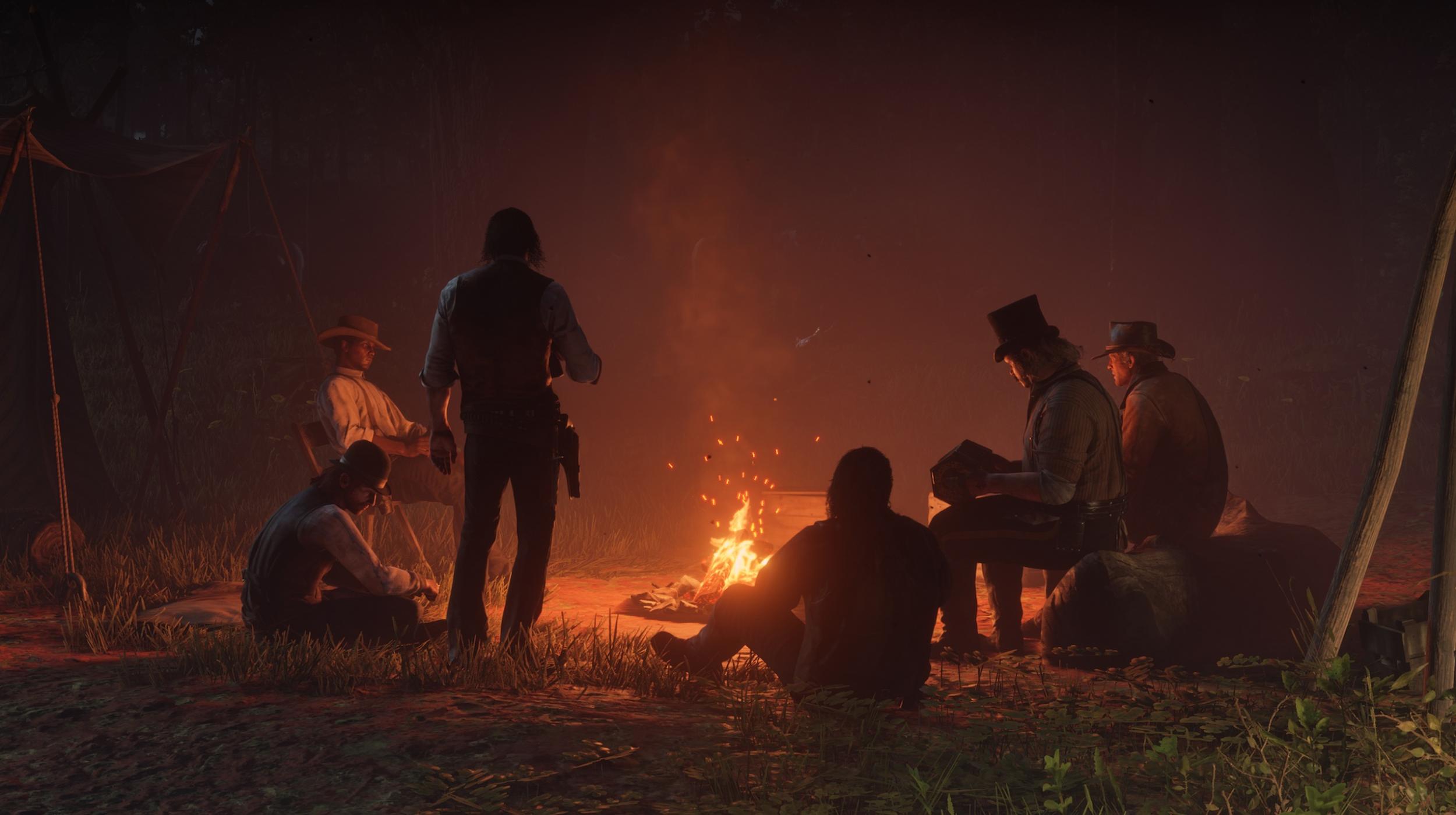

The game encouraging you to buy into the sense of community back at camp was a revelation. Returning to save points has previously been a chore, and in Grand Theft Auto games you’ve never wanted to spend longer than 10 seconds in one of its safehouses. Here though, I actually looked forward to returning to camp, it genuinely felt cleansing somehow. Whether it was the gang getting increasingly hammered around the campfire or the occasional spats between different gang members, these moments are what made the game feel alive.

This was one of the game’s biggest gambles, and a huge amount of time (not least from the cast) must have gone into making the camp feel ever-changing – it was certainly worth it.

Guarma

It’s always a thrill when you go completely off map in an open world game, and Arthur’s brief sojourn to Guarma served its purpose in making you miss Strawberry and Valentine and Rhodes and all their comparative comforts. The “entering Mexico” moment in RDR1 was always going to be impossible to top or recreate, but the “returning to America” one post-Guarma came pretty close, and I never felt as immersed in the game as when a bedraggled Arthur was carried back to Shady Belle by his horse as D’Angelo’s “Unshaken” played.

Guarma itself, though, I soon forgot about. I did enjoy the gang’s marooned-on-a-desert-island period, but it felt slightly lacking somehow. It just wasn’t quite as compelling as other stretches of the game, and I wanted a little more from it given that we never made it to Mexico in this title.

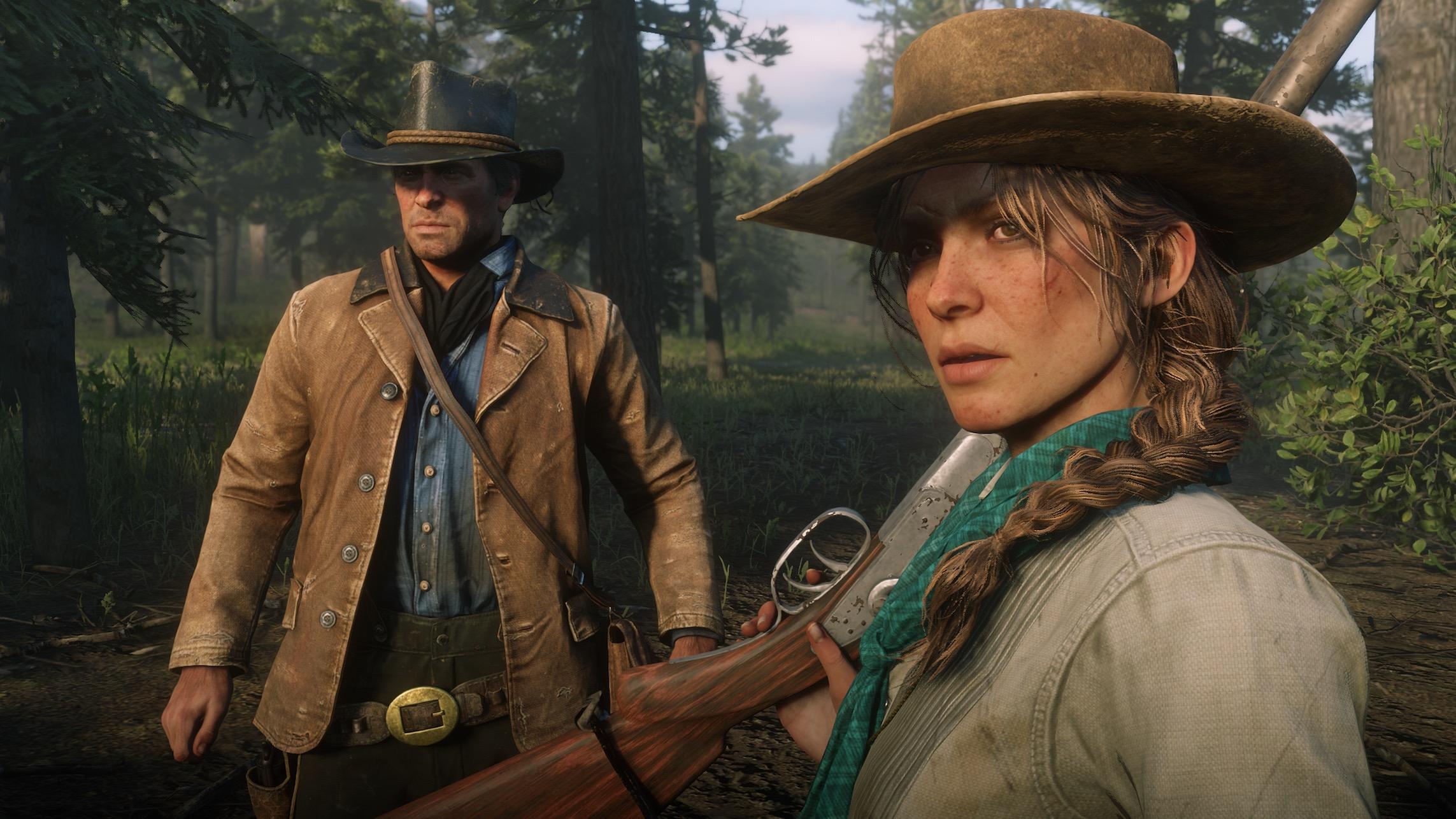

The overpowering of Sadie Adler

I can safely say that I had more feeling toward RDR2’s characters than those of any other game. Tilly, Karen, Hosea – the lot of them: all thoroughly enjoyable characters. Sadie, however, started to irk me by the end, becoming essentially an indestructible superhero in the epilogue. The whole “I don’t need to rely on men” angle was just pushed a few too many times, to the point where it jolted you out of the game slightly, and you imagined the writers fretting about whether the game was feminist enough. I understand the desire to have women feature in the game more outside of domestic scenarios, but this could perhaps have been done more subtly and effectively with an expansion on the suffrage sub-plot. Sadie might also have felt more three-dimensional if we were able to play as her (though I wouldn’t be surprised if we still get to, be it in a future title or downloadable content).

New Austin and beyond

The recreation of a large section of RDR1’s map is probably the most polarising aspect of the game. Tacked onto the end, I had yet to even explore Armadillo and Tumbleweed when the credits rolled. It seems to bug a lot of people that whole towns were added to the game but not really used, and that they’ feel a little empty compared to those on the main map, but I think it was the perfect way to end the game.

We’re greedy when it comes to games in a way that we’re not with films and TV shows. Even though we’ve had hours and hours of enjoyment out of them, you can’t help but want a little more after the main story is completed. For me, New Austin and beyond provided exactly that. We were now in the boots of John Marston, and here before us lied an entire state, and one that we knew would play host to the next events in the RDR timeline. After the emotionally draining main story, the addition of this new land seemed to say “and yet still there’s more world out there, and other humans capable of as much joy and despair.”

Perhaps the addition of a couple of side missions out in the desert would have made the final third of the map feel more cohesive with the rest, but in fairness we did get the Tumbleweed sheriff’s bounties and extra legendary animals, not to mention the cholera bout in Armadillo which was a great touch and very atmospheric.

Creating an ending to a game that has to provide closure while still saying “and now try playing online” is not easy, but I think this free-roaming coda did a pretty good job.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments