Was Alan Sugar the UK's Steve Jobs? How the Amstrad CPC 464 changed computing

Thirty years ago this week Amstrad went up against Apple and launched the back-to-basics home computer

For Lord Alan Sugar, 11 April 1984 was a glorious day. After months of hard work, he took his place in the sumptuous surroundings of Westminster School and, with dozens of journalists sitting before him, lifted the lid on what would, perhaps, be his most famous creation: the Amstrad CPC 464.

As with like inventor Clive Sinclair and his ZX Spectrum before him, he was looking to make his mark in the fledgling home computer industry. He wanted to draw upon everything he had learned from the moment that he had formed Amstrad in 1968 and transfer that into a market that was showing itself to be hugely profitable.

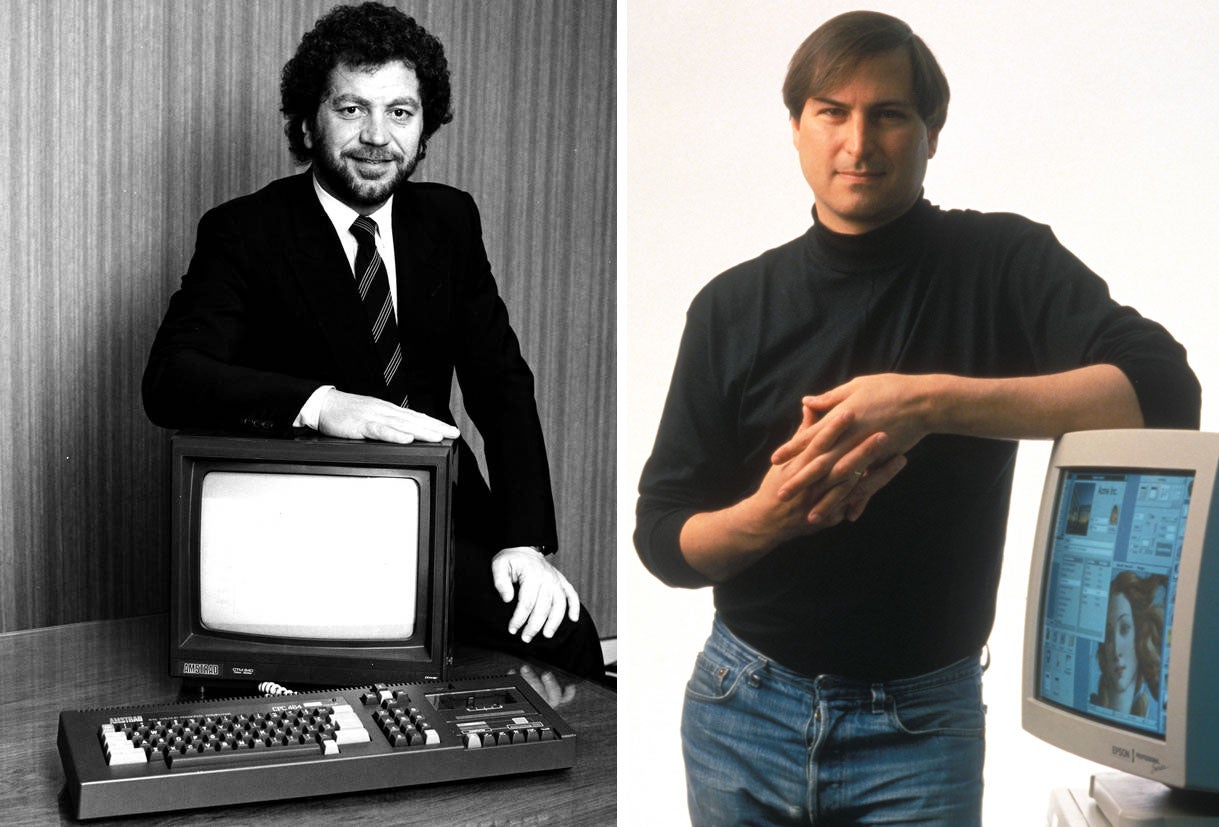

But while Sinclair was his major rival for punters' cash in Britain, there is an argument that he also shared much common ground with Steve Jobs. Although those who worked with him would beg to differ – "It doesn't compute with me at all," says Roland Perry, Amstrad's former group technical consultant, of the comparison – the underlying principle of both men was to make computers as simple as possible.

Both had dragged up their companies by the bootstraps – Jobs in a Californian garage with co-founder Steve Wozniak; Sugar selling car aerials on the streets of London's East End from a van he bought for £50 – and both were keen to be involved in all aspects of their businesses.

"People used to ask whether I'd see Alan Sugar that much. I was like, nah, not very often – only about every 15 minutes," laughs Perry. Both also fell prey to making early misjudgements. With Jobs, it was the approach to former Pepsi president John Scully which led to his subsequent firing. With Lord Sugar, it was his naivety in hiring "two long-haired hippies", which could so easily have derailed his entire foray into computers.

Writing in his autobiography, What You See Is What You Get, Lord Sugar tells of two men who insisted that they could write an operating system for the CPC in just one month but, of course, they couldn't. Stress levels rose, a coder was discovered drunk at home and unable to work and the result was reams of unusable, unintelligible code.

It's a rather ironic tale given that a large part of Jobs' success was due to his hippie leanings (his new-age thinking had him labelled "a goddamn hippie with BO" by his co-workers at Atari). But whereas Jobs took LSD and followed a fruitarian diet, Lord Sugar was impeccably suited, and the respectable-looking tycoon looked out for business opportunities. This kind of thing was a real eye-opener.

"We'd learned very quickly that this computer business wasn't just a case of chucking a bunch of chips into a box and putting a plastic cabinet around it," he wrote. "We were entering a new world."

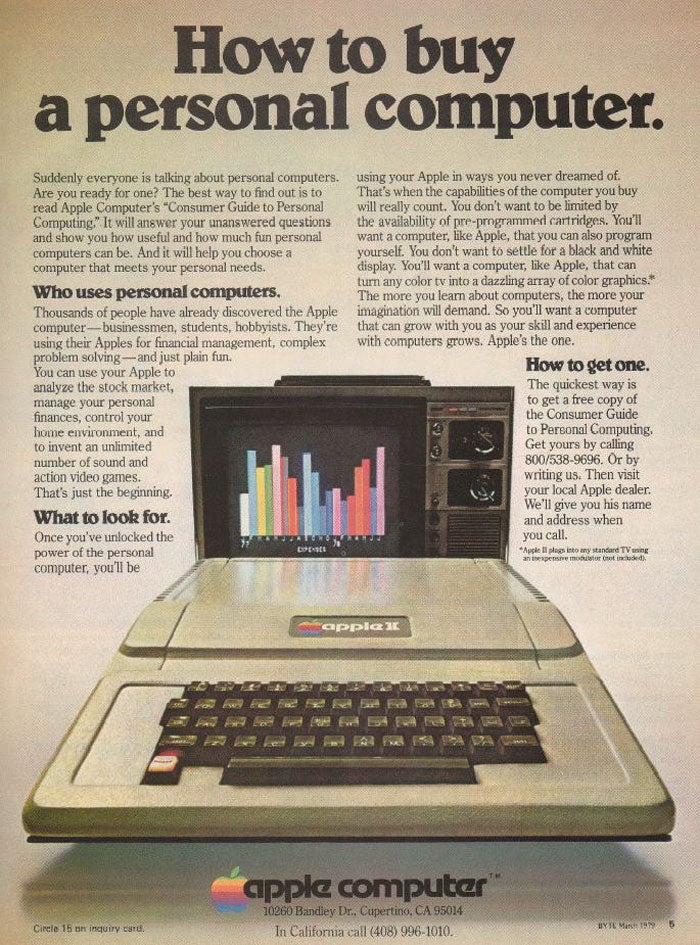

And what a new world that was. UK playgrounds were sliced in two by a silicon curtain: fans of Sinclair machines on one side, admirers of the Commodore 64 on the other. Acorn, Apple, Atari, Dragon, Mattel, NEC and Oric were also trying – and in some cases succeeding – to make their mark. They were the days before mass-market dominance of the PC and it led to lots of eclectic machines and emerging powers.

Lord Sugar came into this cold: his biggest success was with Amstrad's hi-fi systems. Amstrad's hi-fis had no interconnecting wires, just a mains cable and sold in droves. Showing that consumers loved simplicity. Lord Sugar wanted the same for the CPC.

"The audience was the lorry driver and his mate," says Perry. "Alan Sugar had an image of people trudging down the high street in the rain looking for a Christmas present. He assumed they would think, 'Amstrad's hi-fi was OK so I'll buy this computer'."

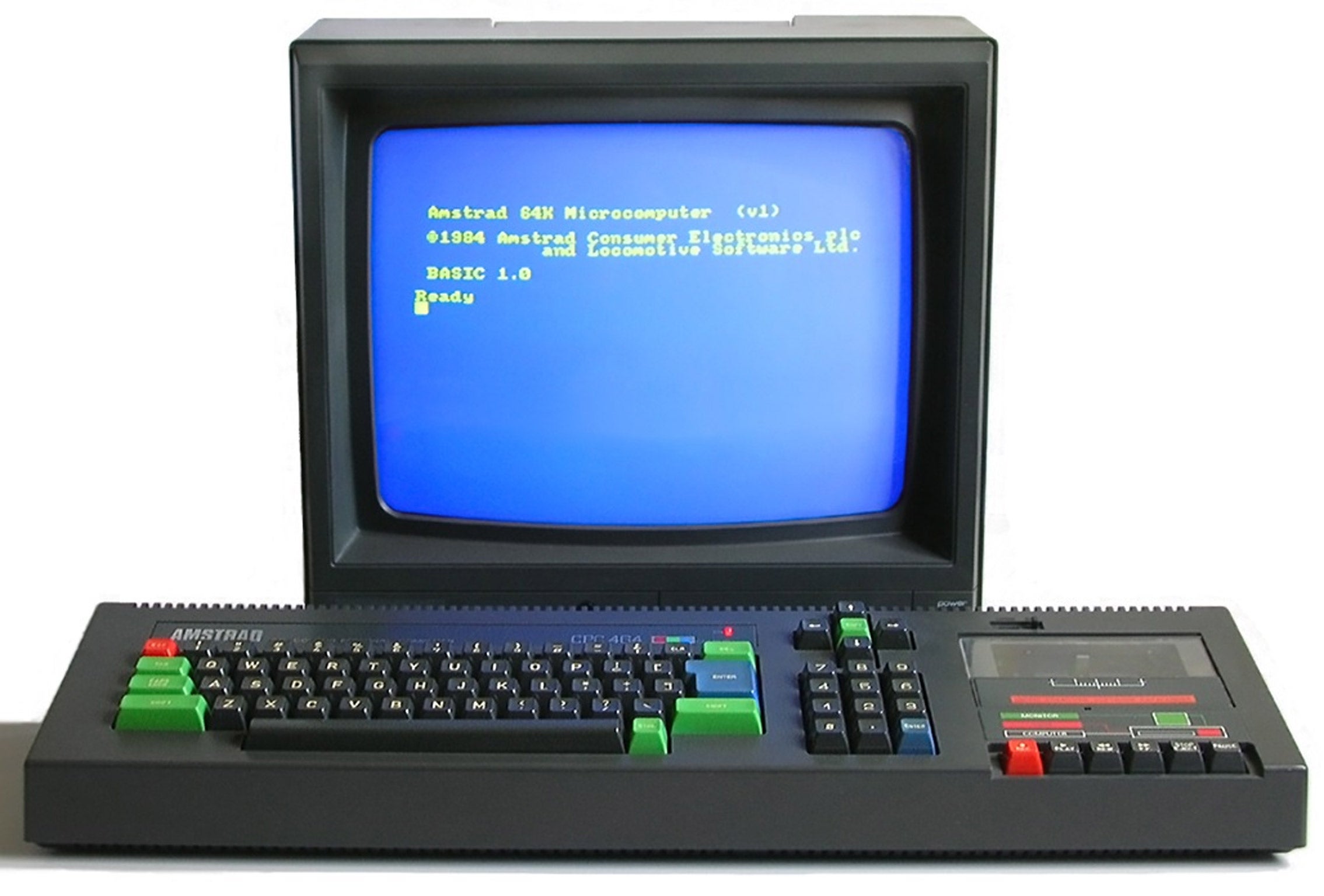

To keep things as simple as possible, the CPC 464 had just two items: a keyboard and monitor. The components, including the tape deck, fitted inside the keyboard and the power supply sat within the monitor. A couple of wires connected the two and they were powered by just one plug. One flick of a switch and the computer was ready to use.

"Alan Sugar didn't want people rolling around on the floor figuring out where to insert things," says Perry, who had been brought on board after Lord Sugar shouted "You're Fired" at his hippies. "It had to be assembled quickly to maintain the enthusiasm."

In this regard, Lord Sugar was again similar to Jobs. The Apple II had been praised by Byte magazine for the ease in which it could be picked off the shelf, taken home, plugged in and used. But then Amstrad was inspired in some way by Apple: its staff would be offered Apple II clones on their frequent sourcing trips to the Far East but Amstrad didn't want to merely rebadge them – it wanted to make its own. "The Apple II gave rise to the idea that Amstrad could include a home computer in its portfolio," explains Perry.

Amstrad sought to keep the price of the machine as low as possible – certainly lower than the $2,638 (£1,575) wanted for the Apple II 48K machine. The CPC 464, with a green screen monitor, cost £199; colour cost £299 (the monitor-less Commodore 64 was £195.95 and the Spectrum cost £175). And it more than matched spec-wise. The 464 had a Z80 processor like the ZX Spectrum and 64k of RAM, like the Commodore 64. It had a palette of 27 colours and ports for peripherals such as a printer.

Journalists were impressed. Following the launch, the setting of which Perry describes as "like something out of Hogwarts, like a chapel", they gushed religiously about the rectangular, plastic, budget buy. "After the People's Car," headlined the London Evening Standard, referring to the VW Beetle, "the People's Computer".

They subsequently sold well. Amstrad quickly added two extra machines: the 664 and the 6128, both with disk drives. By 1990, they had become France's best-selling computer range with 50 per cent of the market and 650,000 sales. Worldwide, they had shifted three million. "We had a computer designed specifically for people in certain countries with France, Germany and Spain being particularly important to us," says Perry.

Amstrad also insisted on amassing a software library, called Amsoft, prior to launch. In the same way that apps became important for Jobs, so software was crucial to Lord Sugar's thinking. One of the launch titles was Roland in the Caves, a subterranean platformer. "Alan had this whizzo idea of naming the creature in it after me," laughs Perry, omitting to also mention that the CPC's codename, Arnold, was an anagram of his first name. "There was this whole series of Roland games."

Many developers nurtured their careers on the CPC. "We spent every waking hour learning to program it and churning out games," says Philip Oliver, founder of Blitz Games Studios and, more recently, Radiant Worlds. "We took a year out of university and made Super Robin Hood on the CPC, selling it to Codemasters for £10,000. It got to number one. Our early success was spawned by the CPC."

Amstrad encouraged people to write software for the CPC. Its manual included the BASIC programming tool as well as simple set-up instructions. "We expected people to go away and write their own programs," says Perry. "We saw ourselves as providing the platform that others could expand on."

Magazines devoted to the CPC continued this trend. "The CPC was like the computer for the everyman," says Rod Lawton, who edited Amstrad Action magazine for four years in the early 1990s. "It could do games, it could do business, it could do education and you could even learn a bit of computer programming. It was the computer for the man in the street."

Although sales of the C64 and Spectrum were far higher - 17 million and five million respectively - without the CPC, Amstrad would not have made its best-selling and affordable PCW and PC ranges. But the CPC remains popular today: enthusiasts continue to produce games for the computer. One small team is working on a CPC version of Street Fighter II. “Programming the CPC today is like some kind of exercise that ultimately improves your skills as a professional,” says Augusto Ruiz. “It's also fun.” Cheap too – CPCs can be picked up on eBay for around £70 and the operating system can be emulated legally and free on Macs and PCs.

But was he really the British Steve Jobs? "Steve Jobs was a visionary who wanted everyone else to understand the amazing possibilities he saw," says Lawton. "I think Alan Sugar is a pragmatic entrepreneur who has a gift for making exciting technology unexpectedly affordable."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks