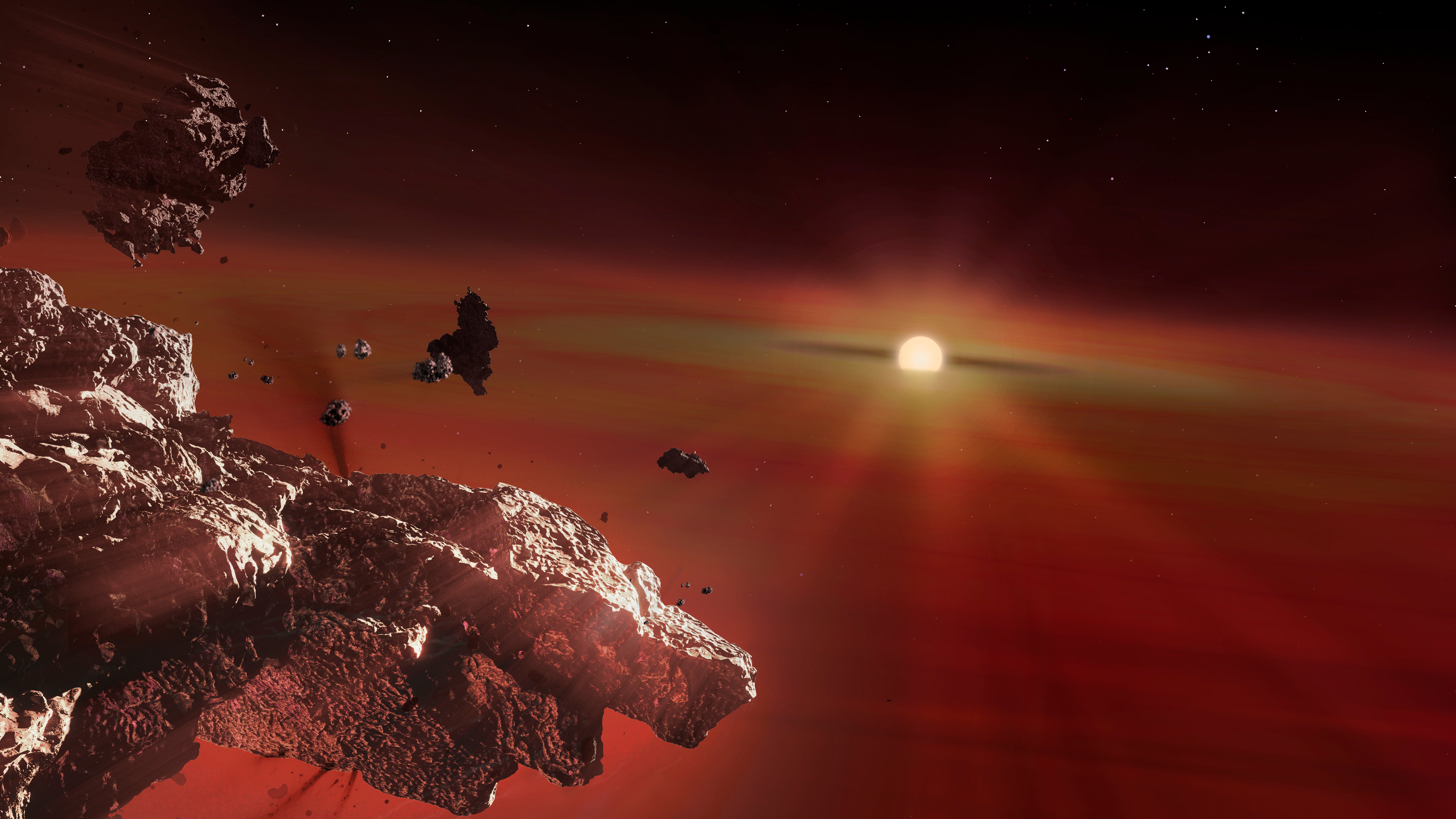

Remains of destroyed Earth-like planets found in dying stars

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Leftovers from Earth-like worlds have been found in dying stars, scientists say.

Those planets would once have looked like our own: rocky, and covered in a crust with a chemical composition remarkably similar to our own.

But they have since been destroyed, and left as remnants in the atmosphere of nearby white dwarfs.

Four stars were found to be hosting the remains in all, including one that contains one of the oldest planetary systems ever seen.

The findings are reported in Nature Astronomy by a team of astronomers who used the European Space Agency’s Gaia telescope.

The researchers were searching through data on more than 1,000 white dwarf stars, when they found a particularly unusual signal from one of the stars.

Further analysis saw them analyse the light from that star, and found that the signal seemed to include lithium. They then looked at more white dwarfs, and found three more that had the element – one of which also had potassium in its atmosphere too.

They discovered that the amount of lithium, potassium and other elements in the form of sodium and calcium matched the ratio of those elements that are found in the crust of rocky planets like our own Earth – if Earth had been vaporised and blended up into a star over the course of two million years.

“In the past, we’ve seen all sorts of things like mantle and core material, but we’ve not had a definitive detection of planetary crust. Lithium and potassium are good indicators of crust material, they are not present in high concentrations in the mantle or core,” said Mark Hollands from the University of Warwick’s Department of Physics.

“Now we know what chemical signature to look for to detect these elements, we have the opportunity to look at a huge number of white dwarfs and find more of these. Then we can look at the distribution of that signature and see how often we detect these planetary crusts and how that compares to our predictions.”

The white dwarfs are remarkable not only as the graveyards of past worlds. They are also very old: the four of them are thought to have used up their fuel as long as 10 billion years ago, and could be some of the galaxy’s oldest white dwarfs.

“In one case, we are looking at planet formation around a star that was formed in the Galactic halo, 11-12.5 billion years ago, hence it must be one of the oldest planetary systems known so far,” said Dr Pier-Emmanuel Tremblay from the University of Warwick, a co-author on the study.

“Another of these systems formed around a short-lived star that was initially more than four times the mass of the Sun, a record-breaking discovery delivering important constraints on how fast planets can form around their host stars.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments