Scientists discover new way to connect human brains to computers - through veins

Novel method offers less invasive approach than other tested brain-computer interfaces, like the one proposed by Elon Musk’s Neuralink startup

A team of scientists have managed to connect a human brain to a Windows 10 computer by threading a wire through a blood vessel.

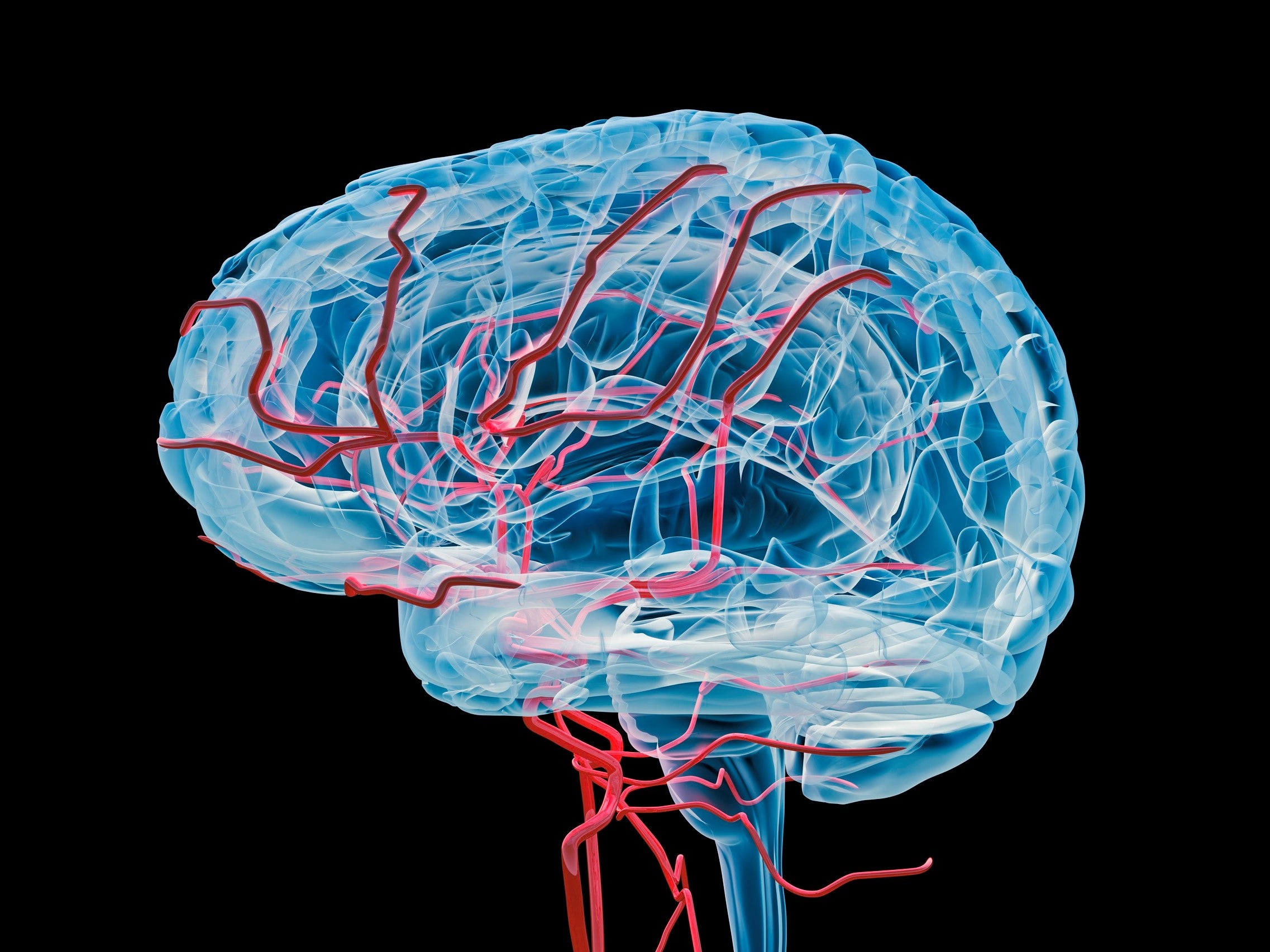

Researchers from the University of Melbourne achieved the feat by inserting electrodes through the jugular vein in the neck and pushing them up to the brain’s primary motor cortex.

Once there, the electrodes were nestled into the wall of the blood vessel where they could detect brain signals and feed them back to a computer.

The approach, which was first theorised in 2016, was successfully tested on two people with the degenerative disease amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS).

The participants were able to control the mouse of a computer connected to their brain by using their thoughts. The results of the study were published in an article in the Journal of NeuroInterventional Surgery last week.

“The participants undertook machine-learning-assisted training to use wirelessly transmitted electrocorticography signal associated with attempted movements to control multiple mouse-click actions, including zoom and left-click,” the study states.

“Used in combination with an eye-tracker for cursor navigation, participants achieved Windows 10 operating system control to conduct instrumental activities of daily living tasks.”

The first participant was able to use the brain-computer interface technology unsupervised at home after 86 days, while the second participant achieved home use after just 71 days of supervision.

The novel method is a less invasive approach than other tested brain-computer interfaces, such as the one proposed by Elon Musk’s Neuralink startup.

In a presentation of the technology earlier this year, Mr Musk showed off a chip that could be implanted by removing a piece of skull.

The University of Melbourne researchers hope to commercialise their method through the company Synchron.

“The motor system, right now, is what’s going to deliver therapy for people who are paralysed,” Associate Professor Thomas Oxley, lead author of the study and CEO of Synchron, told Wired.

“But when we start to engage with other areas of the brain, you begin to see how the technology is going to open up brain processing power.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks