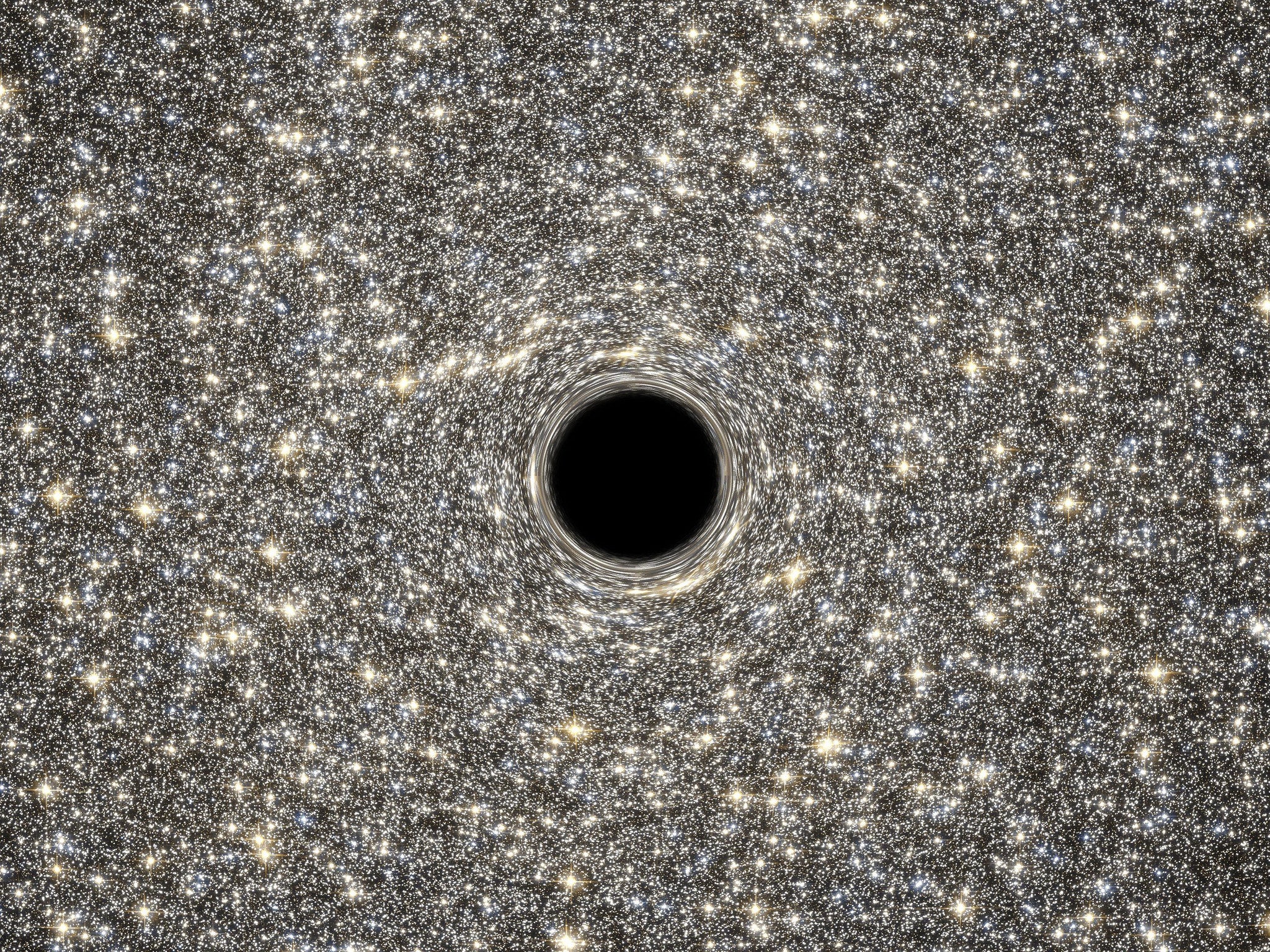

Scientists discover black hole racing through space - but can’t explain why

It is possible that another, as-yet undetected black hole is pulling the one inside galaxy J0437+2456 along

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Astronomers have detected a supermassive black hole moving through space, but do not yet know what is propelling it through the cosmos.

Black holes usually remain fairly static. “We don’t expect the majority of supermassive black holes to be moving; they’re usually content to just sit around,” Dominic Pesce, an astronomer at the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian, said.

“They’re just so heavy that it’s tough to get them going. Consider how much more difficult it is to kick a bowling ball into motion than it is to kick a soccer ball — realizing that in this case, the ‘bowling ball’ is several million times the mass of our Sun. That’s going to require a pretty mighty kick.”

This rare occurrence was found by comparing the speed and direction of supermassive black holes with their home galaxies. Scientists would expect the velocities of the black holes to match those of the galaxies, with any change in direction or speed being evidence of disruption.

Scientists examined 10 distant galaxies and their black holes, specifically looking at those with water in their accretion disks, which are spiral structures that spin towards the hole. As the water orbits the hole it produces a bean of radio light known as a maser.

Read more:

Masers can help measure velocity very precisely when combined with data from radio antennas, using very long baseline interferometry or “VLBI”. This is when radio telescopes measure a black hole from multiple locations and calculate the difference in how long it takes the signal to arrive - essentially giving the network a scope as large as the maximum separation between the smaller telescopes.

Nine of the black holes were not in motion but one - in the galaxy J0437+2456, located 230 million light-years away from Earth and approximately three million times larger that our Sun - was found to be moving at a speed of 110,000 miles per hour.

The cause of this movement remains a mystery, but scientists have two hypotheses. “We may be observing the aftermath of two supermassive black holes merging,” says Jim Condon, a radio astronomer at the National Radio Astronomy Observatory.

“The result of such a merger can cause the newborn black hole to recoil, and we may be watching it in the act of recoiling or as it settles down again.”

The second possibility is that the black hole is part of a binary system, where the one inside J0437+2456 is being moved by another black hole that has yet to be found by radio observation - perhaps due to the fact it does not have a maser emission.

The scientists’ results have been published in The Astrophysical Journal.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments