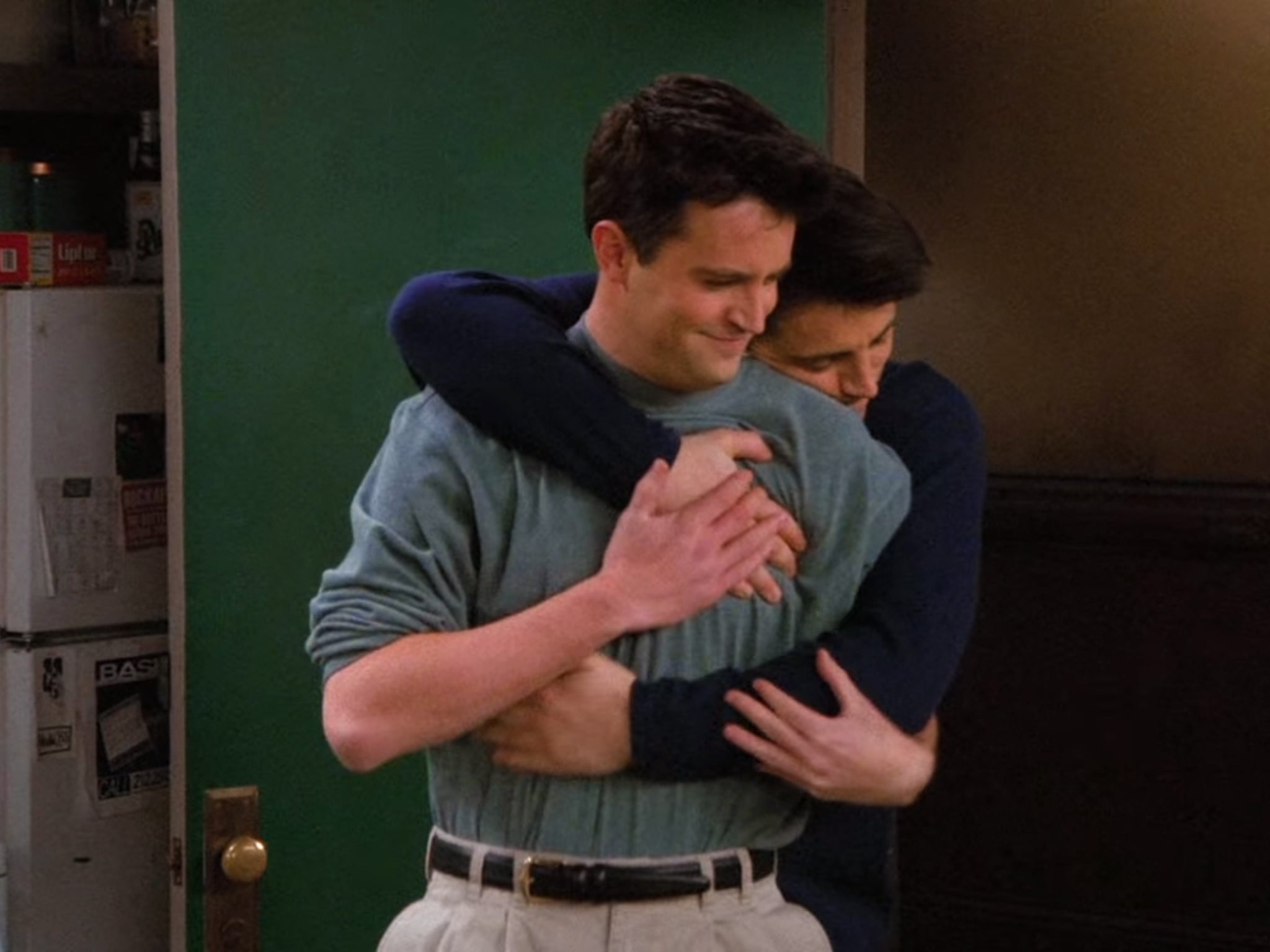

Could friendship apps be the key to combatting millennial loneliness?

As the loneliness epidemic rages on, Olivia Petter examines how making friends online has become a solution for many

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Lily was 26 when she realised every one of her close friends was in a serious relationship. “They were all at a different stage of life to me,” she recalls, two years later. “Even though I never felt like a third wheel, I wanted to branch out and meet new people.” To do this, Lily did what many people her age do when they want something: she went online. “I downloaded Bumble BFF. It took me a while to click with someone, but eventually I met Ria – we had similar interests, approaches to relationships, and mental health journeys. She was also single, which made a difference. Now, she’s one of my closest friends.”

Rewind five years or so, and a story like Lily’s would sound shocking. Bizarre, even. Sure, we’d adapted to meeting romantic partners online, although even that carried a social stigma. But friends? Aren’t you supposed to find them in real life? And shouldn’t you have enough already?

Not exactly. In 2021, one Australian report dubbed millennials and Gen Z the loneliest generations, with one in two Gen Z-ers (54 per cent) and millennials (51 per cent) reporting that they regularly feel lonely – figures that were much higher compared to those of other generations. Meanwhile, in 2019, YouGov found that 30 per cent of millennials “always” or “often” felt lonely, while nearly one in four couldn’t name a single friend.

These stats may come as a surprise to some, particularly those who assume that, having grown up in the age of social media, millennials and Gen Z-ers would have more friends than the generations that came before them. We’re surrounded by constant communication, whether it’s on WhatsApp and iMessage or Instagram and Twitter. Other people are only ever a few taps and swipes away. But evidently, that doesn’t always translate to offline connections.

Enter friendship apps. Since its launch in 2016, Bumble BFF has seen continued growth, with almost 15 per cent of all Bumble users also using its BFF feature, an increase of 10 per cent from the previous year. The service works like its dating counterpart: users can create profiles detailing their various interests, and swipe on other profiles in the hope of expanding their social circle.

Today there are many others like it, including Tinder Social, Wink, Hey! Vina, and Meetup, which connects people with shared interests. Though it launched in 2002 with a purpose to build communities in post-9/11 New York City, Meetup has since become a global success, renowned for fostering friendships around the world. “It may be a perfect storm of reasons why there is a great demand for friendships today,” says David Siegel, Meetup’s CEO. “With many companies still having employees work from home, opportunities to meet people through an office setting have disappeared.”

There’s an unnecessary embarrassment about the desire to make new friends, which shouldn’t be the case

Of course, the pandemic has had a colossal impact on friendships, regardless of your age. More people than ever before are working remotely. Some have moved out of cities. Others have felt compelled to completely transform their lives. All of this will take a toll on your friendship circle. A recent poll by LifeSearch found that almost one in three UK adults had fallen out with friends due to the pressures of the pandemic, losing an average of four friends since Covid began. Meanwhile, in March, Google published a list of our most searched-for subjects over the past 12 months – “How can I meet new friends?” was being searched at an all-time high. And according to BBH Global, the fastest-growing “how to make” search in the UK in 2022 was “how to make friends as an adult”.

“The nature of friendships has changed,” says psychologist Madeleine Mason Roantree. “Not only in the wake of smartphones, but also as a result of how connections transitioned online during lockdown. Collectively, we have learnt we can still maintain a sense of friendship without meeting in person.” That can be helpful, of course, for those who live far apart from one another. But it can also have the opposite effect of giving friends the illusion of intimacy without physical contact, which may only exacerbate feelings of loneliness and social isolation.

“I’ve found making friends much more challenging since the pandemic,” says Jo Threlfall, 30. “I noticed when I started seeing people again that I’ve become more of an introvert-extrovert hybrid and get quite exhausted after too much socialising.” When Threlfall moved cities and found herself feeling adrift without a core social circle, she joined Bumble BFF. “I’ve met two people there and we see each other when we can for walks or coffee,” she says.

Ellie, 24, has also had great success using friendship apps following a move. “I moved to Belfast from London with my partner, and struggled to make friends as I felt like a bit of an outsider,” she recalls, noting that she then joined the now-defunct Girl Crew app to meet people. “Funnily enough, a lot of us were in a similar situation; none of us were Belfast locals but we were struggling to make friends.” Soon they were regularly going out in groups for dinners and cocktail tastings.

“I’ve also found there’s an unnecessary embarrassment about the desire to make new friends, which shouldn’t be the case,” she adds. “I’ve got over that, and will now happily approach people who seem my vibe and [whom] I want to befriend. But an app [can] facilitate this conversation and make the process a lot more accessible for those who are more nervous about these kinds of interactions.”

Given their popularity, friendship apps are launching all the time. Take Pally, which is aimed at millennials. Instead of featuring photos in the style of a dating app, it applies social psychology to match its users. “I’ve moved around a lot, living in five cities in five years,” says Pally’s founder Harry Hubble, 24. “I realised how hard it is to make new friends after education. You have to go to countless events, communities, clubs, and filter through everyone you meet to try and find the people who are really compatible with you. Even as an extrovert, this gets very draining very quickly.”

Hubble believes the risk of using a friendship app is much the same as using a dating app – that you’ll end up “scrolling and swiping mindlessly for hours, rather than building true social connection”. The key is to find ways of looking beyond profiles and getting the technology to facilitate this, he says. “Our key differentiator is that we consider the whole person when introducing them to new people,” he explains. “Their identity, values, personality, lifestyle and interests.” The app also matches people into groups as opposed to matching individuals, as the former makes users feel safer.

So much about friendship is chance – it means that we don’t always end up hanging out with people who are really, truly compatible with us

Given the way the world has changed, perhaps it’s no surprise that friendship apps are becoming increasingly popular. Dating apps have now become largely mainstream, so it makes sense that the same technology would eventually be applied to friendships. However, as any seasoned dating-app user will know, meeting people online isn’t always as easy as it might seem. Sure, you can easily match with someone and start talking to them. But who’s to say they won’t ghost, breadcrumb, or zombie you later on?

“The same classic internet-related worries persist on friendship apps, but they’re almost irrelevant,” says Kate Leaver, the author of The Friendship Cure. “After all, there are different things at stake when it comes to friendships and romantic relationships. For example, you’re probably less likely to engage in [the] push-pull, game-playing dynamic that has come to define the modern dating landscape. When you’re looking for friends, the whole process can be a bit more straightforward.

“The comforting thing about a friendship app is that you can reasonably expect people who’ve downloaded it to at the very least be open to having a new friend. Like with dating, it also allows you to be more selective. So much about friendship is chance, and that can be a beautiful thing, but it also means that we don’t always end up hanging out with people who are really, truly compatible with us.”

As loneliness continues to become a national concern, and friendships naturally drift away post-pandemic, it’s important to actively look for solutions in helping people form connections. It might seem counterintuitive to do it on a screen, given that it’s the same prism through which so many of us became isolated in the first place. But, evidently, it’s working for many people. As for the stigma we attach to meeting people online? “It isn’t an issue,” says Leaver. “When you consider how important it is to have friends, how little does it really matter how you made them?”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments