The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

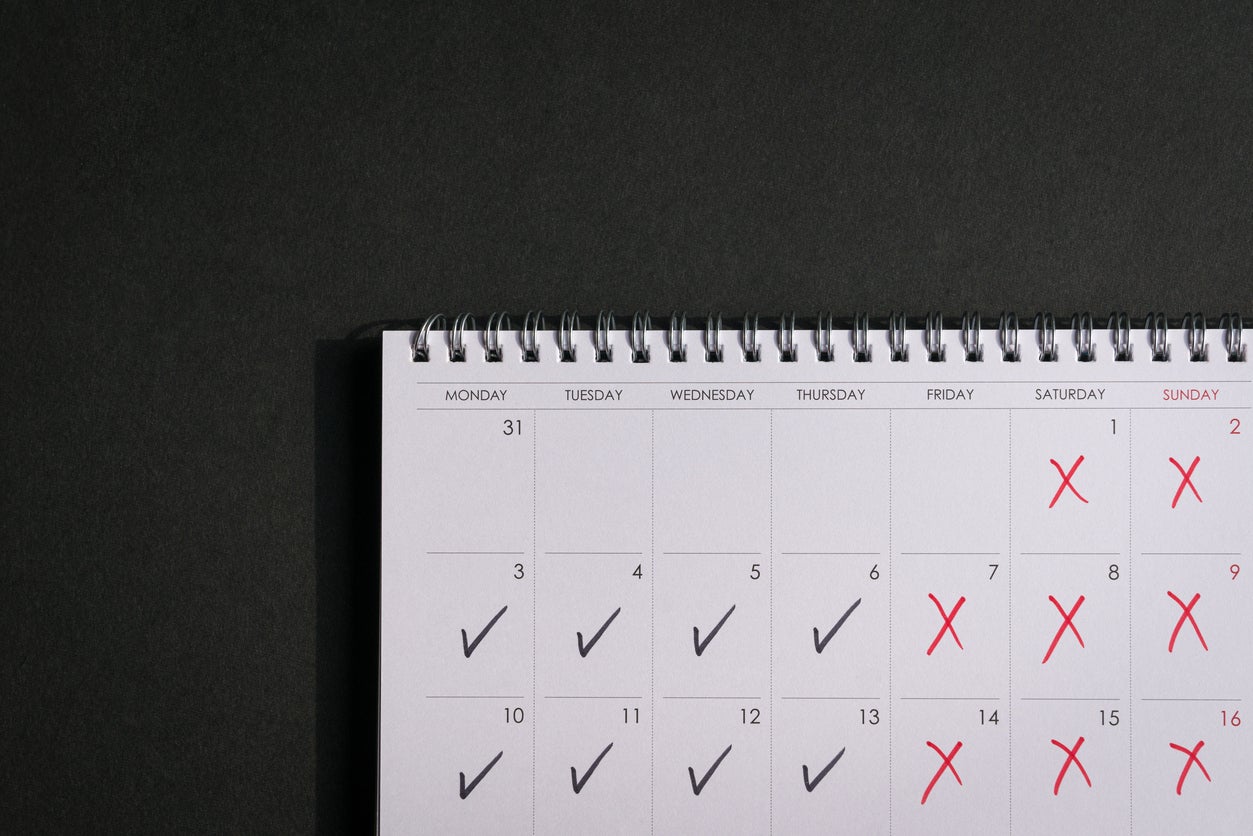

Four-day working weeks make us happier and more productive – here’s why they won’t happen any time soon

Nearly every trial seems to confirm that having an extra day off is a win-win. Helen Coffey asks the experts why it hasn’t taken off yet, and whether a three-day weekend will ever be the norm

If there were ever proof that humans don’t like change, surely it is the four-day week. The straightforward concept – that the working week should be the equivalent of one day shorter but for the same pay – has been swirling around for years without ever really taking off.

But all of a sudden, the world and his wife seem to be gabbing about the idea. The Unison union has officially backed it, demanding the new Labour government takes action to ensure more companies offer this way of working. Campaigners have stepped up their efforts, with both the launch of a new UK-wide pilot and the results of a substantial trial in Portugal being announced this week. And then there’s the latest success story from South Cambridgeshire, where the district council boldly tested a four-day week for hundreds of staff starting in January 2023.

The first and only council to implement the innovative move, the Lib Dem-run local authority stuck to its guns despite fierce resistance from the previous Conservative government. But after ignoring calls from the Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities to shut down the scheme, South Cambridgeshire has reaped the rewards.

“The brave and pioneering trial has clearly been a success,” it said in its recently published independent report, citing a reduction in staff turnover of 39 per cent, an increase in the average number of applications for roles of 53 per cent, and an annual saving of £483,000 in agency costs as a result of hard-to-fill roles attracting permanent staff members.

Far from “costing the taxpayer money”, as was the Tory argument, it has saved them money. Council services also improved: the time taken to make a decision on planning applications fell by 1.5 per cent; 3 per cent more emergency repairs for housing were completed within 24 hours; and overall complaints fell by 10 per cent during the 15-month trial. It’s worked so well that the council is continuing, with hopes that others might follow suit under a more sympathetic Labour government.

It follows a year-long trial, the world’s largest to date, in which 61 UK organisations across the private and charity sector, from fish and chip shops to breweries to housing associations, signed up to implement the four-day week in 2022. Orchestrated by the 4 Day Week Campaign, the pilot was, in the majority of cases, an unequivocal success. Almost 90 per cent confirmed they were still operating the policy one year on, while more than half said they’d made the measure permanent. It sparked the decision to run a similar six-month trial this autumn, with British companies invited to apply and results to be presented to the government next year.

Why was it so successful? Because both employees and employers get something out of it, claims Joe Ryle, director of the campaign. “At a fundamental level, it’s giving people the ability to lead happier and more fulfilled lives, achieve a better work-life balance and have more time for resting, hobbies, socialising with friends and family, and taking on caring responsibilities. That extra day off is really valuable.”

It also seems to be a win-win for the employer: “Productivity is often maintained or improved,” says Ryle. “You see better recruitment, better retention, fewer sick days and better gender equality – it means fewer women, who still take on a disproportionate amount of childcare duties, have to go part-time.”

It hasn’t worked in every case. Asda recently announced it was scrapping its particular brand of four-day-week experiment after staff complained of exhaustion; engineering and industrial supplies company Allcap was forced to abandon its trial of offering one extra day off a fortnight due to staffing shortages, with the extra day’s work forcing other team members to pick up the slack. But it’s worth noting that the former was offering compressed rather than reduced hours, requiring workers to put in 44 hours a week across four 11-hour shifts. And though the experiment failed in the latter, business owner Mark Roderick remained positive about the scheme, telling the BBC: “If we could recruit more staff without a massive increase to our wage bill, we’d do it tomorrow. We were just too short-staffed to make it work.”

The word “productivity” is key to why the four-day week has potential. Despite having some of the longest average working hours in Europe, the UK economy is currently stuck in a productivity slump. From 2010 to 2022, the annual average growth in UK GDP per hour worked was just 0.5 per cent, way behind Germany, the US and France, with little sign of improvement in recent years.

And, although it might seem counterintuitive that more would get accomplished if people worked for 20 per cent less time per week, that is a fundamental misunderstanding of how productivity works, says Bart van Ark, managing director of The Productivity Institute, a government-funded, UK-wide research organisation.

Putting in more hours doesn’t necessarily mean more productivity

“If you look at it mathematically, putting in more hours doesn’t necessarily mean more productivity,” he says. “If you work eight hours and then add a ninth and a 10th hour – would it give more productivity than those first eight hours? Well, no, because after that we get tired.”

Indeed, the institute has posited three factors for the UK’s slowing productivity, none of which has anything to do with a dearth of “hard work” or long hours: chronic underinvestment from the government, a lack of joined-up policies and institutional fragmentation, and a failure to share innovation, technology and best practices outside the nation’s top-performing businesses.

In fact, there’s much research suggesting that overworking doesn’t equal more output. A study from Boston University found that managers at one consultancy firm could not tell the difference between employees who actually worked 80 hours a week and those who pretended to. There was also zero evidence that employees who worked fewer hours accomplished less, or that the employees who overworked accomplished more.

Part of our current productivity problem is that “we define it too narrowly”, argues Madeleine Dore, author of I Didn’t Do the Thing Today: Letting Go of Productivity Guilt. “We’re told to work harder, longer and more optimised, but our days rarely unfold in perfect order – people call in sick, priorities shift, we fluctuate in our focus and attention. When we judge ourselves or others by how much we do, what we do is never enough.”

Van Ark agrees that, while people often say that if you want to be more productive you need to work harder, the real question is: what does “harder” actually mean? There is little evidence that going down the opposite route and working more hours – for example, Greece’s recent decision to tackle its productivity crisis by switching to a six-day week – will result in more work getting done. “It often comes down to working smarter and organising better,” he says.

One way that smarter working could negate the need to work that fifth day per week will be via technology. This was, after all, what eventually helped shift the norm from the six-day week prior to the 1930s to the five-day week that’s now commonplace; the second industrial revolution at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries introduced new machinery that improved productivity and made processes faster.

AI, as much as it often prompts suspicion from workers, is the next big leap in technology that’s likely fundamental to making the gains that would allow a 20 per cent reduction in hours in certain jobs. If ChatGPT can, for example, do the equivalent of an hour’s worth of research in seconds, a worker’s productivity shoots up in line with their time being freed up.

While tech is what enabled previous working patterns to change, we have failed to adapt to account for the huge advances made more recently, says Pedro Gomes, an economics professor at Birkbeck and author of Friday is the New Saturday: How a Four-Day Working Week Will Save the Economy. “What’s missing is, when we look at the last 30 years, everything has changed in terms of communication, technology, women’s participation in the workforce. All these structural changes in our economy have made it very different to the 20th century, but we’re still working the same way. We didn’t adapt.”

The funny thing is, criticisms of it now are the same as the criticisms of the five-day week in the 1930s

Current technology, though making work easier and faster, has conversely made it more intensive while raising expectations of workers’ output. “It translates into all these work-related mental illnesses like stress and burnout,” says Gomes, highlighting that there are parallels between the modern need to reduce working hours and the landscape that prompted the same argument a century ago, when there were compelling physical reasons, such as factory workers on mass production lines getting RSI. In the 2022 4 Day Week Campaign trial, 71 per cent of employees from participating organisations reported feeling reduced levels of burnout, alongside improvements in physical health and wellbeing.

The experts I speak to agree that the four-day week might look different based on the sector and industry – in some cases seeing a reduction in hours across five days, for instance. But the experiments so far suggest that the concept can work for every kind of organisation if adapted to suit.

“In principle, it could apply to any industry,” agrees van Ark. “Organisations that rely heavily on office work do offer additional opportunities – employees can work more from home and choose different working hours.”

But even sectors that are much more dependent on staff being in the workplace, such as shops and factories, have been included in successful trials. “It may sound more complicated initially, but the waste management team on South Cambridgeshire Council is an interesting case because they managed it just by rejigging their work week and reorganising their processes. This experiment has shown it can be applied quite widely.”

Gomes suggests the same thing, pointing to a cross-industry pilot of 41 organisations in Portugal, which included a nursery. It was a customer-facing business that people assumed would be incompatible with a four-day week. But they managed by hiring just 5 per cent more staff, which saw a huge drop in absenteeism.

The future’s bright, you might say. But there is one, huge stumbling block in the way of achieving this “every weekend’s a bank holiday” dream: that pesky, oh-so-human aversion to change.

“Private sector companies are averse to experimenting with the way we work,” says Gomes. “It’s puzzling because they come up with new products and new markets, but when it comes to innovation with different ways of organising work, they don’t even try.”

It took the pandemic for the widespread adoption of remote working, for example, despite that technology already existing. The four-day week is unlikely to experience a similar “leg-up” in the form of an unforeseen global event.

Looking back 100 years then, the six- to five-day week transition was a decades-long process. First, innovative companies tried it. Then, trade unions started to push for it. Finally, the government legislated for it. We can expect a similar trajectory with the four-day week now, say the experts – the first two steps are already starting to happen – but no matter how successful the latest tests have been, this was never going to be an overnight change.

“The funny thing is, criticisms of it now are the same as the criticisms of the five-day week in the 1930s: that it’s a ‘utopia’, that it can’t work across every industry,” observes Gomes. “It’s just because it’s hard to change – we’ve been organised around the five-day week for 50 years. We grew up with the five-day week and people can’t conceive that it could be different.”

But it could be. And, if history teaches us anything, it more than likely will be. Maybe not tomorrow, or next month, or next year. But in 10 years? It’s certainly possible that the four-day week could be a reality “for the majority of workers”, argues Gomes. Nothing is guaranteed though – “it won’t happen unless we all do our bit and try to keep advancing it. Governments, unions, companies and civil society need to be pushing for it.”

If they do, the four-day week won’t be a utopia but a reality – and we’ll wonder why things were ever different. In this instance, a change really is as good as a rest.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks