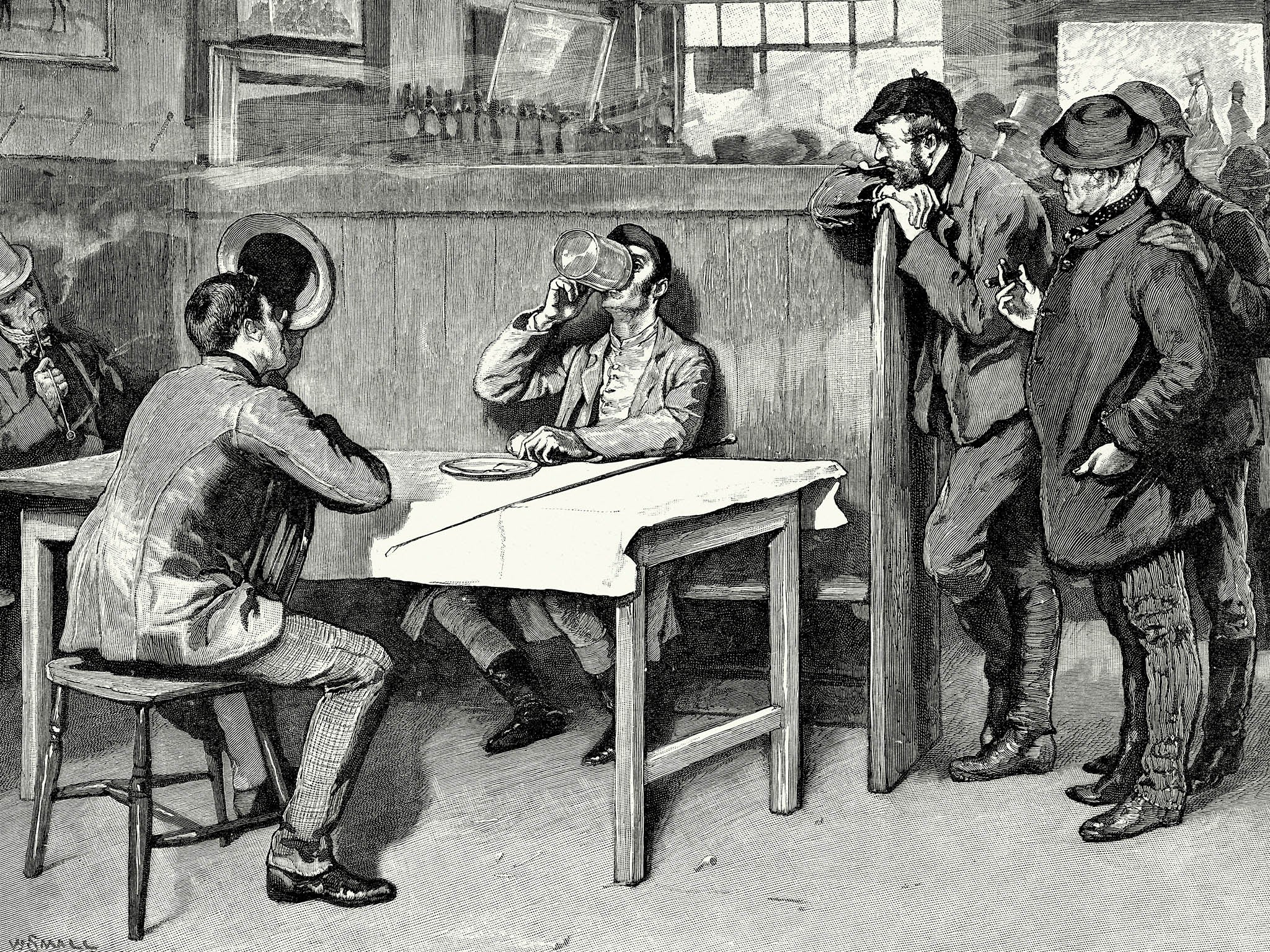

The trouble with cask: is temperature holding traditional draught ale back?

As a declining industry looks for ways to reassert itself, Jo Turner considers the coolness of cask beer – and whether the consumer’s own knowledge should be trusted

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When was the last time you had a really good pint of draught cask ale? Satisfying yet refreshing, full of flavour, topped with a carpet of smooth hoppy bubbles singing of warm autumn evenings – a pint that represents “the best of what beer has to offer”?

Recently, I hope – but maybe not recently enough. Perhaps, whether you consider yourself a cask drinker or not, the last time you ordered a hand-pull it was a little bit “meh”.

When industry accreditation body Cask Marque released its annual report last year (its 20th anniversary) it marked a step down from a more bullish position. Something, it said, has gone wrong.

Yes, editor Matt Eley opened, when it’s good it’s very, very good. But after another year of declining sales – 6.8 per cent across the category – denial is no longer an option.

That hefty piece of analysis titled Cask Reconsidered found an industry dogged by issues around perception, quality and consistency. And follow-up research released just before Easter weekend (NB – it was hot) confirmed the biggest issue for consumers: temperature.

I get it. I’d like to drink more cask. But particularly in summer when London’s (relatively) extreme heat proves too much for this Scottish Highlander, concerns about temperature and refreshment sway me towards something familiar and, sadly sometimes, boring.

My concerns aren’t unfounded. The recommended serving temperature for cask beer is 11-13C. If the cellar is too warm or cold it will affect the conditioning of the beer, which is still an unfinished product on arrival. But Cask Marque’s research found one in three pints were served over 14C last summer – even in January one in five were still too warm.

On top of this, although the “ideal” temperature satisfies most regular drinkers, of those surveyed 64 per cent said they would like to try cask served below 11C – warmer than lager but colder than what they’re used to.

Compounding all of this is the fact that 90 per cent of cask ales end up hanging around beyond their three-day shelf life, according to CGA food and drinks researchers, further detracting from the flavour.

So what to do? Do consumers know what they’re talking about? Research suggests they don’t – but this is the problem. When it comes to temperature, telling people they’re wrong is never a good business strategy. And when a beer is not fresh or has a fault, it’s more likely to be abandoned than brought back to the bar and swapped for another. The drinker simply assumes it’s not to their taste.

Nadia Murray of Sharp’s brewery in Cornwall says understanding, or lack thereof, is one of the main hurdles brewers and publicans come up against. The market has changed, and consumers don’t always know the difference between cask and keg beer (see below). Though in many ways they are two sides of the same coin, cask beer is perceived as an old-fashioned drink compared to trendier kegged craft beers.

Sharp’s, which produces the UK’s biggest selling cask ale, Doom Bar, is meticulous about quality and consistency, as I found on a recent visit to the brewery in windswept Rock. As well as working with Cask Marque – which visits 20,000 pubs a year to perform quality checks and training – Sharp’s provides separate education programmes for stockists and its own “Quality Assured” accreditation for pubs that don’t have a Cask Marque subscription.

Murray says there are more than 100 parameters to be checked from the beginning to the end of the process, from the malt to the pH, microbiological tests in the lab and finally on the supplier end – and batches don’t make it out until they’ve been tasted for quality by the brewery’s panel of experts, some of whom have been comparing pints of Doom Bar for over 12 years.

“It is up to us as a cask beer brand leader to change the misconceptions young people have and to find solutions to encourage them to try cask ale,” Murray says.

“This includes developing more contemporary brand designs and experimenting with the serving temperature of cask ale.” As a result, the brewery is currently trialling a chilled version of its prize product at selected outlets, with an extension of this expected later this year.

Sharp’s is well resourced compared to many smaller brewers, but training for stockists by larger producers and bodies like Cask Marque will surely have a knock-on effect for quality across the board. And ensuing the beer is being looked after properly, as well as responsive moves like colder serves, could be key to preserving a heritage product without letting it be held back by traditionalism.

The idea of a Doom Bar Chilled might be heretical in some circles. Then again, it might be a gateway product.

Scratching your head at “the difference between cask beer, real ale and keg beer”? Here are the basics.

Traditional cask-conditioned beer undergoes a second fermentation in the cask itself, as it still carries an amount of live yeast when added to the container. It will finish conditioning and maturing at its destination venue, and is served without the use of gas; pulled by hand or by gravity, with all carbonation (usually a light fizz) a natural product of fermentation. It is a fresh product and once a cask is tapped it should be used within three days.

Keg beer meanwhile finishes fermenting at the brewery, may be pasteurised to kill off leftover yeast and preserve shelf life, and is propelled to the bar using gas – normally CO2. It is served colder than cask beer, around 2-8C.

There’s more skill and effort required to look after cask beer, with a number of steps to be taken over several days when it arrives at its destination venue before it can be tapped and served. When a keg arrives you can stand it in the cellar, connect a coupler and you’re ready to go.

Real ale is a term coined by Camra (Campaign for Real Ale) in the early 1970s to distinguish traditional draught cask beers from the mass-produced, processed and highly carbonated beers (predominantly lagers) which had become ubiquitous. It requires that the beer be produced and stored in the traditional way; be unpasteurised and unfiltered; ferments in the dispense container and is served without adding gas. It’s worth noting that Camra’s definition now encompasses bottles and cans too, so while cask-conditioned beer is real ale, not all real ale is cask beer.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments