The worst things you can feed to your children

Is it sugary drinks that are doing the damage? Could processed foods be to blame?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.All around the world, child obesity rates are rising. In the Americas, 31 per cent of children are now overweight or obese. In Europe, that number is closer to 40 per cent. Even in regions where obesity is less of an epidemic, it's becoming increasingly problematic.

And the trend, no doubt, has a lot to do with whatever it is that overweight kids and teenagers are eating. Is it sugary drinks that are doing the damage? Could processed foods be to blame? Is there a collection of popular things that parents should stop feeding their children so often?

Curious to find an answer, researchers at Duke National University of Singapore took a closer look at the types of food that are associated with overweight and obese children. Using the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children, which recorded the diets and body mass index (BMI) of nearly 4,500 children in England in the 1990s, they tracked what the kids ate and what happened to their bodies over the course of three years. What they found is convincing evidence that certain foods might be causing disproportionate harm.

Specifically, the kids who regularly ate potato chips tended to gain the most weight. "We found potato chips to be one of the most obesity-promoting foods for youth to consume," the researchers wrote. "Potato chips are very high in energy density and have a low satiety index, yet they are commonly consumed as snacks."

French fries, fried chicken and fish, processed meats, and fatty spreads (like butter)—performed poorly, too. As did just about anything with added sugar—think desserts, sweets, and sugary drinks. And refined grains, like bleached flour, which are found in most processed foods.

Foods cooked in oil, whether fried, sautéed, or even roasted, were linked to weight gain, too.

But there's also a nuance to the things that appear to make kids fat: they pack calories, but don't fill anyone up.

"Just because a food has more calories doesn't mean it results in more weight gain," said Eric Finkelstein, who teaches at the Duke Global Health Institute at Duke University and is the study's lead author.

"There are foods, like potatoes, which aren't inherently bad for you because they fill you up," he said. "But when you turn them into french fries and potato chips, they tend to result in weight gain."

Why exactly that is, is unclear, but it might have to do with the added fat. Researchers have long studied why some foods are more satiating than others. A 1996 study found that fatty foods, surprisingly, tend to be less filling. Carbs and protein-dense foods, meanwhile, tend to be just the opposite. The problem, explained in Adam Drewnowski and Eva Almiron-Roig's 2010 book "Fat Detection," is likely that fats are more energy dense, but no more filling—so kids eat the same quantity, but in doing so consume more calories.

Finkelstein adds that calories from liquids are particularly problematic, because they're less satiating than those from solid food. Sodas and other sugary drinks, in other words, are doubly harmful.

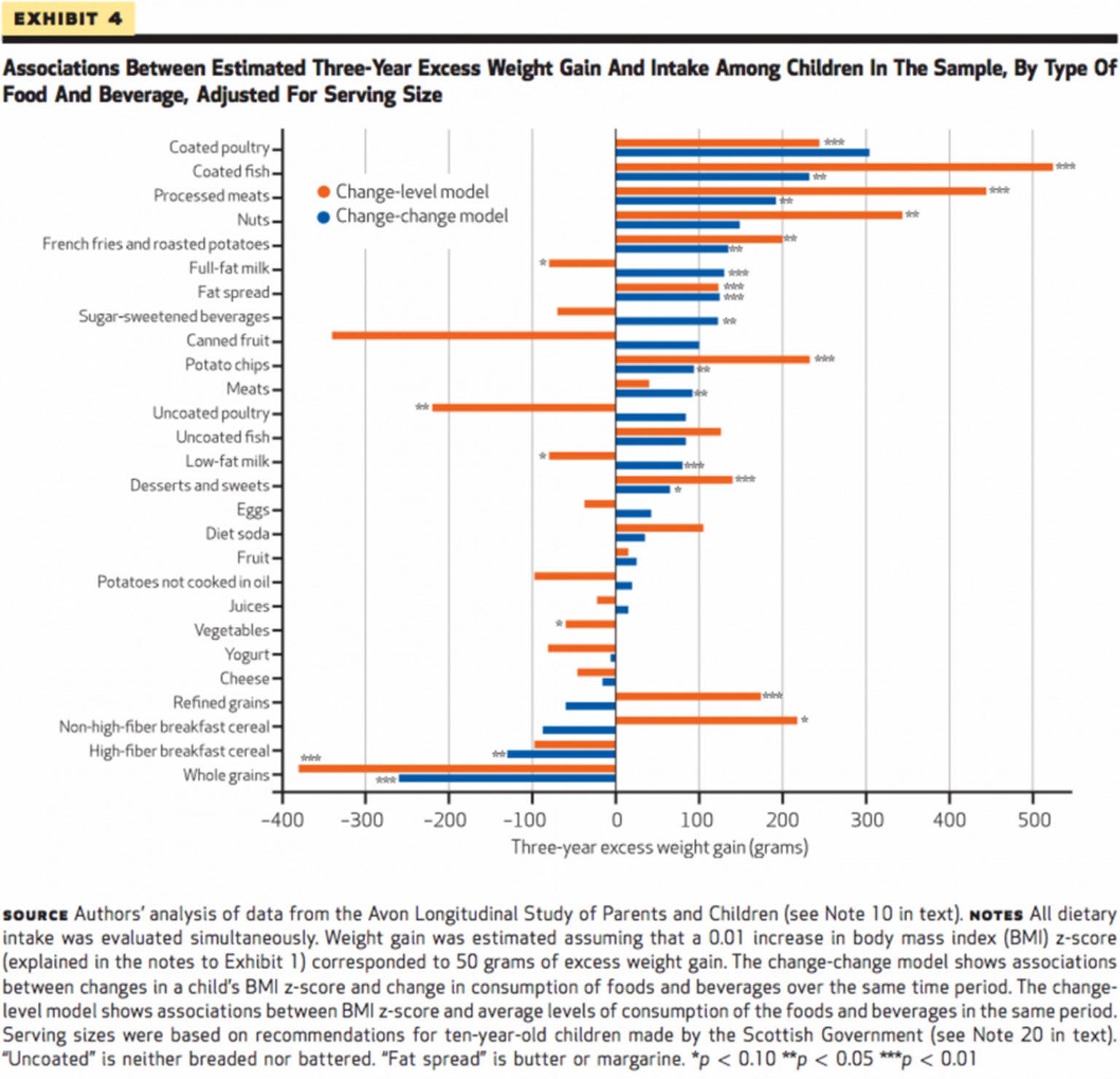

The chart below, plucked from the study, shows the full list of foods. The ones with two and three stars mean the effect was significant. Interestingly, only three categories seem to have had a large positive effect, fighting against obesity: poultry that isn't breaded or fried, high-fiber breakfast cereals, and whole grains.

A look down the list tells an interesting, if not all that surprising, story. The results are similar to a 2011 study, which looked at adults. Kids who eat a lot of fatty, sugary, and fried things tend to gain weight. Those who favor processed foods—both meats and grains—end up heavier too.

But just because the findings help to reinforce things that doctors and dietitians have been saying for years doesn't mean that they aren't useful. After all, many of the foods are eaten not only because they are delicious, but also because they are cultural staples.

Understanding the consequences of celebrating them too much or too often, especially for children who don't have the same control over what they eat, is an important step.

Fish and chips, for instance, while a much adored English meal, might not be the right thing to regularly feed children, as Olga Khazan noted in the Atlantic. Nor are Cheetos, Doritos, Lays, and other popular snacks—most of which are processed—in the United States. Or sodas, which, the researchers concluded, is a particularly important thing for parents to understand in the United States. "Reducing the consumption of these beverages in the United States is likely to have a greater positive impact on weight outcomes than in the United Kingdom."

None of this is to say that an occasional treat is out the question. But it does give credence to the idea that everyone might be better off if there was a clearer disincentive to eat certain foods, and, especially, to feed them to kids.

"The idea of freedom for kids as it relates to what they eat isn't really there," said Finkelstein. We force them to go to school, we don't let them eat or smoke. It's not inconsistent with government policy to say 'okay, we're going to do some things in schools to restrict access to certain foods."

"People who push back on this don't understand the reality that overweight kids almost certainly become obese adults," he added. "Whatever happens when kids are young is almost always irreversible."

Copyright: Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments