Michael Twitty: The culinary historian shedding a new light on the slave trade

Instead of talking about slavery with images of whips and chains, the culinary historian uses another route, food. Julia Platt Leonard finds out how the food of the southern states of America were transformed by traditions brought over by African slaves

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

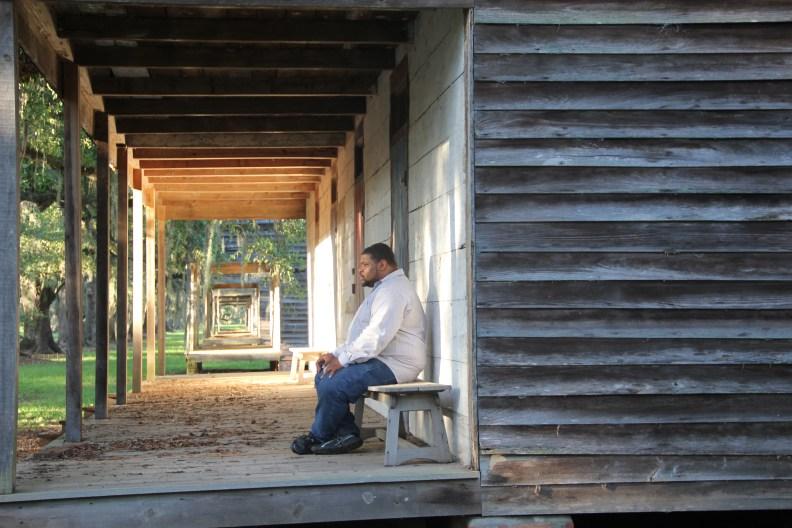

Your support makes all the difference.He calls it the Southern Discomfort Tour and for many Americans – particularly those in the South – what Michael Twitty does is uncomfortable. Twitty is a culinary historian, a historical interpreter and food writer. He’s travelled across the southern US tracing the routes of his own enslaved ancestors and telling a story of slavery that many would rather ignore.

At a lecture at the National Maritime Museum in London, he told the audience, “We’re just not allowed to tell those stories.” The scale of the history of slavery in America is staggering.

Just a floor above the lecture room is an exhibit charting the transatlantic slave trade – the largest forced migration in history. British and British colonial ships bought an estimated 3.4 million Africans in just under 150 years.

But Twitty says while Britain has acknowledged the role it played in slavery, the US has not. “You go to a museum in Great Britain and slavery is a shame. It’s like blood guilt. It’s a casualty of Empire. In America, it’s a glitch on the way to American democracy.” The average enslaved person, says Twitty, was sold 2-3 times during his or her life. Their stories – including those of Twitty’s ancestors – have remained largely untold.

In 2011, Twitty decided to change that. He researched his own family tree and now helps others tease out the threads that connect them back to Africa. He calls it “uncracking the code” of their American story. He documents his work in the blog Afroculinaria and now in a book out in August called The Cooking Gene.

Twitty knows that the sheer enormity of slavery can make it difficult to comprehend. For him, food is a way of understanding the slave experience – making it real and personal. Food became a way to get closer to the past. “People will not listen to me if I talk about whips and chains all the time. So I had to go another route.” He began researching central and west African food traditions that the slaves brought with them and how those transformed the food of the South. “If I can’t know these people in every single detail then maybe I can know their lives that are behind their food.”

Twitty felt the best – the only – way for him to do this was to immerse himself in their world. He learned how to butcher a hog with a hatchet and blunt knife, make fire with a flint and steel, and learn what time of year a possum was best eaten. He picked cotton in a sweltering field for sixteen hours. Now he regularly interprets the cooking of enslaved people at plantations across the South. He’s cooked a dinner at a plantation in North Carolina where slaves lived in a four-room slave house with twelve people crowded into each room. “The bottom line is you go into these spaces and they are haunted: literally and figuratively. They are uncomfortable spaces.”

“You don’t understand anything until it’s 102 degrees in Montgomery, Alabama and you have to make that food over an open hearth.” he said. The life of the enslaved cook was one of gruelling, relentless labour where they routinely had to lift pots that weighed 27 kilos. “Your back hurts. There is hair burnt off your face and arms and you get cuts that you don’t even know you had. You can’t even imagine what it would be like to do that every single day with four hours sleep a night.”

He recounts how at one plantation event, visitors giggled when he spilt water while lifting a heavy pot, “…not even realising that if I was an enslaved cook and I made a mistake that was noticeable, what do you think would happen to me? Think they’d be giggling? No.”

Sharing stories of African American food and cooking he says, is a way to reclaim history. “Let’s put the seed in the ground and let’s see where the seed grows. And maybe if the seed grows well then I will have collard greens and I can make that heirloom collard green into something.” Those heirloom collard greens, or foraging, or nose to tail cooking were all part of the slave’s life out of sheer necessity. “It’s our heritage, it’s not some cute little trend…our people did that every day and night to survive.”

Twitty says while his work may make people uncomfortable, his goal is reconciliation, not retribution. But he says first people must acknowledge what happened and that, “…there is power to be ceded or shared.” Ultimately, he wants people to come together. He talks about one time when he cooked at a plantation and local African Americans and whites came together for the first time in the act of eating and sharing food. “We are a dysfunctional family but we are related to each other,” he says. “We will either die together or live together.”

The Cooking Gene, published by Amistad Press is out 1 August this year. For more information, go to afroculinaria.com

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments