The transformative power of fermentation

Susan Low meets travelling ‘fermentation revivalist’ Sandor Katz, on a mission to demystify a process that has played an important cultural and ritualistic role in human life for millennia

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Chocolate, cheese, wine, beer, sourdough, coffee… a world without these life-enhancing treats (or necessities, depending on your outlook) is too sad to contemplate, particularly with the festive season coming up. There is a common denominator, of course: they’re all products of fermentation.

Fermented foods – and not just cheese and booze, but trendier foodstuffs such as kimchi, kombucha and kefir – are having their moment. In 2020, the global fermented food and ingredients market was valued at £424bn and is projected to reach over £656bn by 2027; more than a third of that growth is projected to come from Europe.

What’s driving the interest? Researchers cite several factors: increasing awareness among the health-conscious; the rising need for food preservation; increasing urbanisation and resultant purchasing power; consumer preference for “healthy” food; the move towards plant-based diets; and increasing obesity and associated digestive problems (fermented foods can help alleviate some symptoms). The Covid pandemic has increased demand too, specifically for probiotic-containing foods, which may help maintain a healthy immune system.

Katz: the ‘fermentation revivalist’

Fermented foods are undoubtedly becoming more popular – and perhaps better understood, too. And if one man could be cited for bringing fermented food into public awareness, it’s Sandor Katz. Katz, who calls himself a “fermentation revivalist”, travels the world running workshops and talks, spreading the word about the transformative power of fermentation.

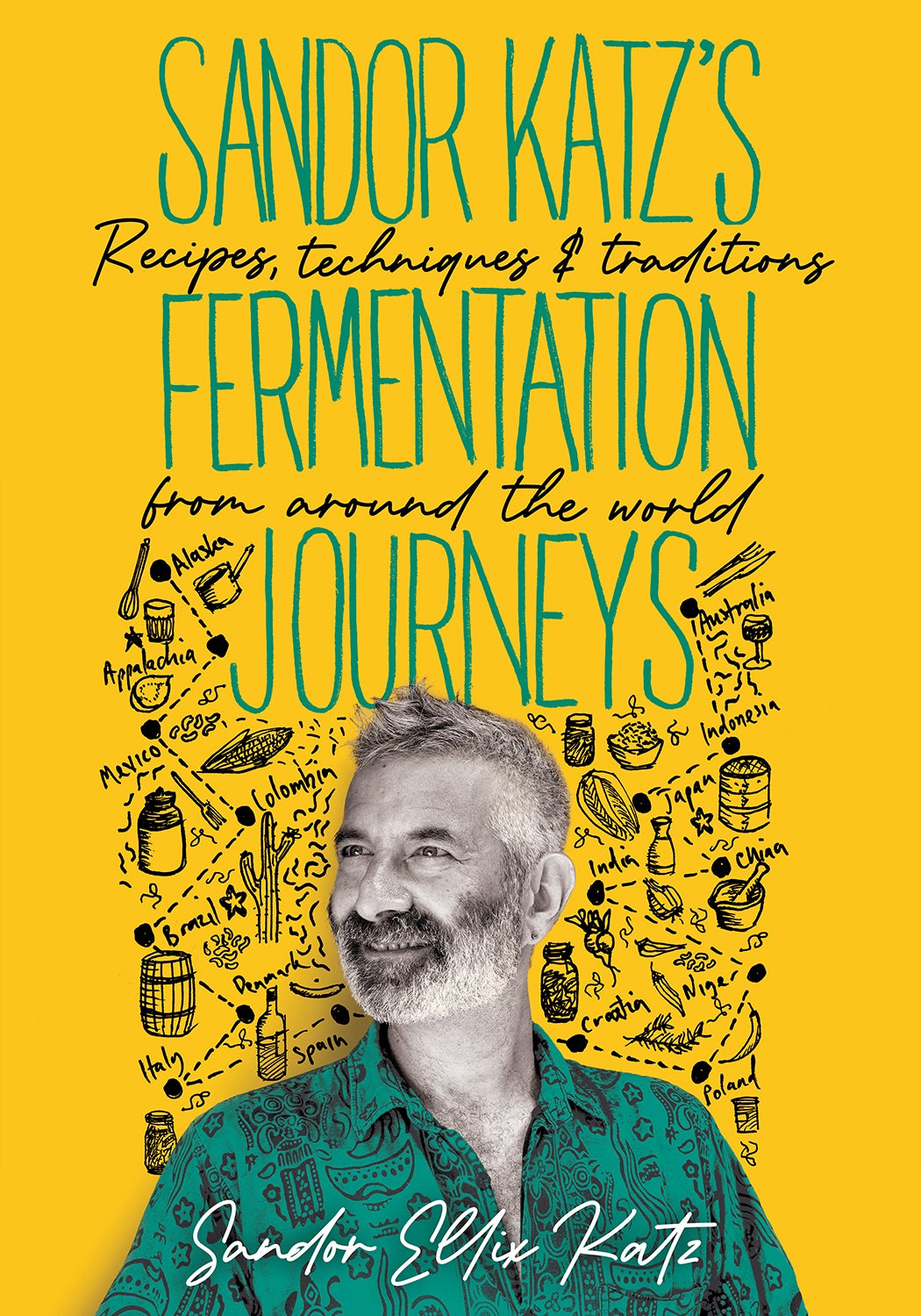

A Brown University-educated native New Yorker, now living in a “vibrant, extended community of queer folks” in rural Tennessee, Katz has written a definitive book on fermented foods. The Art of Fermentation (2012) won a prestigious James Beard Award, sold more than 500,000 copies and has been translated into a dozen languages. He’s also written Wild Fermentation (2003) and Fermentation as Metaphor (2020), followed by the recently published Sandor Katz’s Fermentation Journeys: Recipes, Techniques and Traditions from around the World (2021).

If there’s anyone who knows about the benefits that microbial life can have on human life, it’s Sandor Katz. It’s therefore slightly ironic that, thanks to a somewhat less positive microbe (Covid, again…), our interview about his latest book takes place on Zoom, rather than face to face. On screen, his kitchen looks like a film set for an Alexander Fleming biopic as curated by Wes Anderson. His kitchen shelves are lined with rows of neatly arranged jars and bottles, crocks and containers, all filled with various ferments, pickles and pastes – the things that add life to food, and that have shaped his own life and career.

More than a hipster trend

On Zoom, as in real life, Katz is erudite yet down to earth, earnest yet modest, with a clear vision. He says: “When I call myself a ‘fermentation revivalist’, I’m talking about trying to demystify fermentation, to help people feel comfortable with the process, and if they’re so inclined, to try fermenting for themselves at home.

“Fermentation has been so integral to how people everywhere make effective use of the food resources available to them, yet in our time of convenience food, and with fewer people involved in the production of food, the process has disappeared from most peoples’ lives. Most people have gotten very out of touch with fermentation – even though everybody, everywhere eats and drinks products of fermentation every day.”

Katz’s decades spent travelling and learning have opened his eyes to the diversity and ubiquity of fermented foods – and he wants to put paid to the idea that fermented foods are merely a hipster trend.

“It’s hard for me to think about fermentation as a fad,” he says. “Sure, there are hipster kombucha taprooms in Brooklyn and LA that may not be here in 25 years, but fermentation is just so integral to how everybody eats food. I’m excited that there is heightened interest and awareness, but the basic fact of the importance of fermentation to how we eat has not changed at all. What’s new is that people are thinking about them as being fermented. People are interested in the bacteria and the potential probiotic benefits. That’s the thing that’s changed.”

A world of fermentation

Fermentation Journeys is all about Katz’s journeys to societies in which traditional fermented foods still play an important cultural and ritualistic – as well as nutritional and gastronomic – role. His work as an activist and teacher has brought him to the experimental kitchens of Noma restaurant in Copenhagen to investigate various types of garum, and to the remote Indian Himalayan village of Kalap to learn about an unusual local starter culture called phab or faf.

On the Caribbean island of St Croix he learned about mauby, a fermented drink made from the bark of the soldierwood tree and, closer to (his) home, about the nearly forgotten process of salt-rising bread in Appalachia. Many of his trips have brought him into contact with local indigenous people around the globe, including in Colombia, where he met indigenous people from a number of different traditions.

These encounters have given him “a greater appreciation for how people not only have a practical dependence on, and relationship with, these foods, but also a spiritual connection to them. A lot of the traditional fermented products I learned about [in Colombia] have central ceremonial and ritualistic roles in the spiritual life of the community. I knew this in the abstract, but it was interesting to meet people and see how the ceremonial contexts for these foods are so central to them.”

Fermentation and human culture

A recurring theme in Fermentation Journeys is that of food security – a topic that we have all been compelled to consider in the past 18 months with the pandemic. And here again, fermentation has a role to play, Katz believes.

“The pandemic – in particular all these supply chain disruptions – has made it a bit more real for people how vulnerable this system of centralised production that we’ve created can be, and the importance of local food production. For entirely practical reasons, every region of the world is more secure, more stable, if the bulk of the food that they’re consuming is produced regionally because they’re not subject to the same kinds of potential disruptions,” he says.

Katz’s evangelicalism for fermentation is deep-rooted. Far more than being a poster boy for microbes, Katz is a deep thinker on the role that fermentation plays in human culture, a theme he explores in his book Fermentation as Metaphor (“It’s a short read for one chilly day when you’re cosy indoors – it’s meandering thoughts on this theme of the multiple meanings of the word ‘culture’,” he says.)

Yet he’s clear-eyed and realistic too. “At one level, a lot of the methods of fermentation are just practical,” he says. “Like, how do you turn the most perishable foods, like milk, into stable foods? How do we prevent scurvy in places with long winters, and make sure that people have some vegetable-source foods that they can eat regularly throughout the winter? But on another level, it’s part of the content of ‘culture’ – the lineage that we come from. It’s the favourite foods that our grandmother made, and that she learned how to make from her grandmother. It’s part of people’s cultural identity.”

Not everyone who got into making sourdough during lockdown is going to become a dedicated “fermento” and make their own yoghurt or kefir on a weekly basis. Learning to make sauerkraut won’t stop the next pandemic. But Katz believes fermentation has intrinsic value to societies around the world and society as a whole. “We have every reason to want to safeguard the methods that we have used for hundreds and thousands of years to produce food. I’m not against people’s embrace of convenience, but I think it’s really important that we not lose our connection to the older traditions,” he says.

Something to ponder when you next butter some hot sourdough or pop the cork on that celebratory bottle of bubbly.

How to make farinata

“Farinata is an Italian fried cake made from chickpea flour. Variations of it are eaten in different regions of Italy, as well as France, and beyond. It is known by a variety of names, among them socca, faina, cecina, and torta di ceci. I was curious about these chickpea cakes, because I have often been asked what bean fermentation traditions exist outside of Asia, where the practice is so widespread. I have not encountered farinata in my travels, but I have done some investigating and experimenting.

“None of the recipes I have found for farinata call explicitly for fermenting it. They all mention letting the batter sit for a period, with suggestions ranging from 20 minutes to hours. According to Enrica Monzani, who studies, teaches, and blogs about the cuisine of her native province of Liguria in Italy, the proper amount of time is ‘at least four hours, better eight’. Her blog, A Small Kitchen in Genoa, guided me as to proportions and technique for making farinata.

“According to Enrica, the reason for the long soak is because ‘the flour must absorb the water very well’. No doubt this is true, and when the ingredients need time to sit together, what happens if you give them more time, measured in days rather than hours? In my experiments, fermenting the farinata batter for a day or two or three, until the batter gets frothy and foamy, makes for a luscious, light, and creamy treat that is almost like a fluffy omelette or souffle.”

Time frame: 2 to 3 days

Makes: One 25cm cake

Equipment:

Whisk

Copper or cast-iron crepe pan with a 25cm diameter (if you use a bigger pan, scale up the recipe so that the layer of fresh batter in the pan maintains a depth of about 7-9mm)

Ingredients:

100g chickpea flour

1 tsp/5g salt

3½ tbsp/50g olive oil (or other vegetable oil)

A small amount of finely sliced vegetables (onion, sweet pepper, artichoke hearts, mushrooms, anything) and/or grated or crumbled cheese, to sprinkle onto the surface of the farinata (optional)

Method:

Combine the chickpea flour with 300ml water, using a whisk to work it well and eliminate any lumps of flour (do not add salt until later).

Ferment this batter, loosely covered, for a few days (shorter in warmer places, longer in cooler places).

Whisk at least once each day, until you notice that it is getting frothy. Then, it is ready to use.

Preheat the oven at its highest setting.

Preheat the pan in the oven. I use a cast-iron pan. A lot of the recipes specify a copper pan, which, alas, I do not have.

While the pan is heating, add the salt to the batter and give it its final whisking.

Carefully remove the hot pan from the oven.

Add the oil and make sure it spreads evenly over the entire surface of the hot pan.

See this blog post for Enrica’s most helpful advice about how to pour the batter into the hot oil gently, so it floats above the oil rather than mixing with it. Slowly pour the batter down the length of a wooden spoon, held at a 45-degree angle just above the centre of the pan, onto the hot oil.

If desired, sprinkle some small pieces of vegetables or cheese, or whatever else you can imagine, onto the surface of the batter.

Place the pan on the bottom rack of the oven and bake for 10 to 15 minutes, until it has set and it is golden in colour.

Grill for a few more minutes to brown the surface.

Cool for a minute, then cut into pieces.

Enjoy farinata fresh and still warm.

Recipe extracted from ‘Sandor Katz’s Fermentation Journeys: Recipes, Techniques and Traditions from around the World’ by Sandor Ellix Katz (Chelsea Green Publishing, Oct 2021) and is reprinted with permission from the publisher.

Sandor Katz gives frequent talks and demonstrations online and in person. Visit his website to find out about upcoming events.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments