Chef Maunika Gowardhan: ‘Indian food is so much more than chicken tikka masala’

Gowardhan tells Prudence Wade why India has the best street food and how she fell in love with cooking through her grandmother

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Chicken tikka masala is a much-loved dish, but it’s only scratching the surface of delicious food cooked in a tandoor.

The tandoor – a clay oven used in a lot of Indian cooking – offers a world of possibilities, and that’s something chef Maunika Gowardhan is keen to uncover.

It’s not like there’s just one type of chicken tikka. From murgh malai to reshmi tikka, the options are endless – and Gowardhan, 44, had the best exposure possible growing up in Mumbai.

“I grew up on really, really good street food – India is such a vibrant, diverse space. In every region you find some sort of street eat somewhere, and every corner of the country will have some sort of kebab or tikka,” she says.

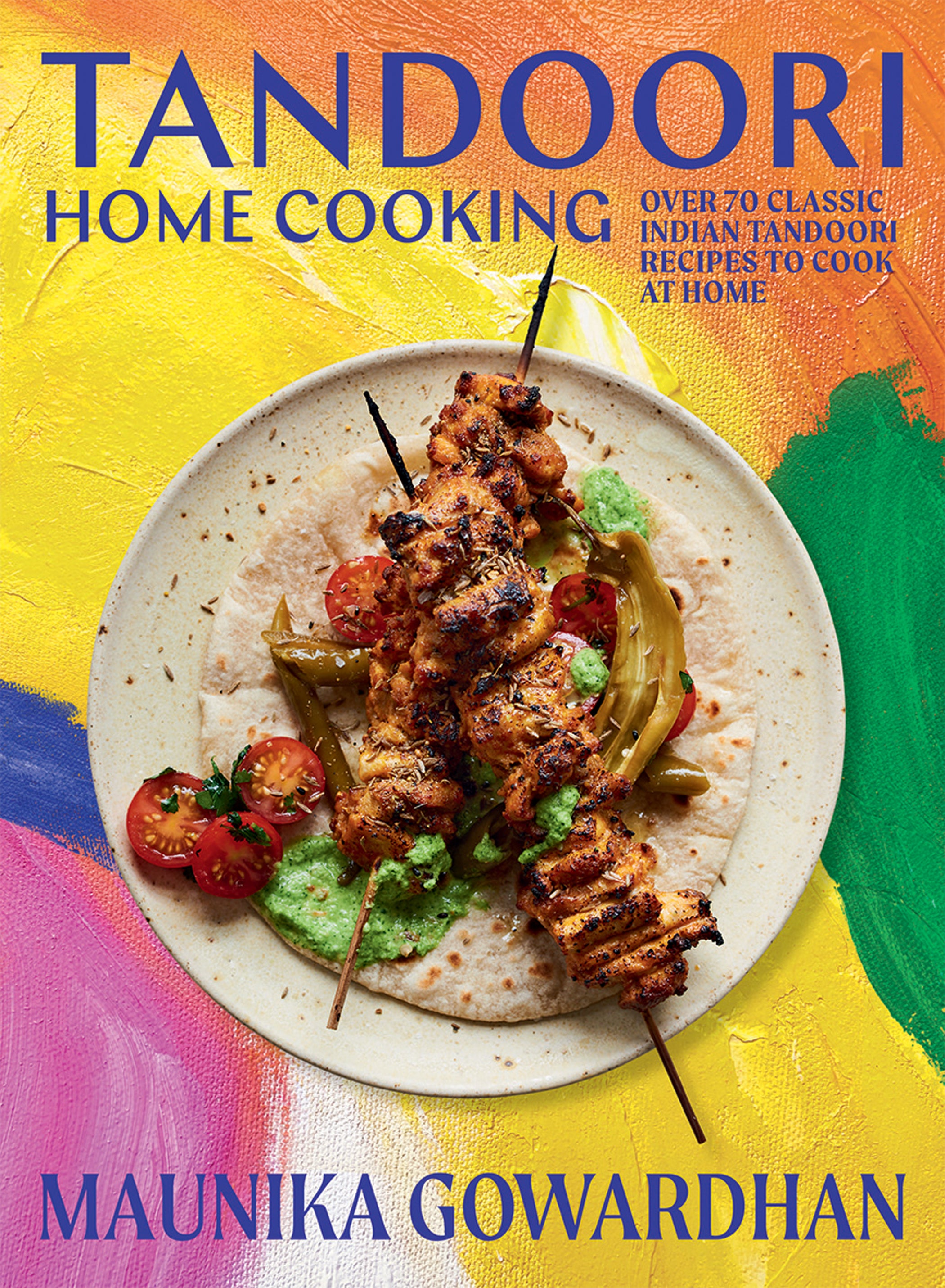

“Sometimes, books can have one or two of those recipes – you can’t have a whole book on just that” – and that’s what Gowardhan has set out to change in her latest cookbook, Tandoori Home Cooking.

She wants people to recognise the history of the tandoor: “What really sets it apart, for me, is that it’s a cooking technique that is dated back to the Indus Valley [from 3300 BCE to 1300 BCE]. It’s something that is so historic, that has so much of a rich heritage – it’s such a vital part of how we eat, not just in the streets of India or in restaurants, but even in our own homes.”

Even though most homes in India don’t have a clay oven, there are plenty of techniques to replicate that smokey flavour.

“When you have a look at the way a clay oven works, essentially it’s heat that’s 360 [degrees],” Gowardhan explains.

“In our domestic kitchens, the endeavour is to replicate that – conventional ovens provide heat in an encapsulated space. So they are similar, but they’re not the same.”

The main difference is the coals at the bottom of a tandoor – when fat drips from any meat or anything else you put in the clay oven, it drips onto the coal and the smoke that is produced gives the food that “charred, grilled smokey flavour”, she says.

But how can you get that at home? One of Gowardhan’s genius tips is making smoked butter.

“You can store it in the fridge, and when you start basting your food with that smoked butter, you’re getting the charred, smokey flavour that you’re really yearning for in tandoori dishes.”

Not that Gowardhan has been perfecting smoked butter from a young age.

“I’m going to put my hand up here and say when I first came to England [25 years ago], I didn’t know how to cook Indian food,” Gowardhan, who now lives in Newcastle upon Tyne, confesses.

She came to the UK for university, during which she was “thrilled” to be away from her parents with that “sense of freedom”.

But after moving to her first house and getting a job in the city of London, Gowardhan says: “It slowly creeps up on you – when you go to an unfamiliar place, what you really miss is that familiarity.”

That’s when Gowardhan started to learn how to cook Indian food, because “I craved it and yearned it all the time”, she says.

She would ring her mother back in India and ask for simple recipes – daal, rice, green bean dishes.

“I cooked not just for sustenance, I cooked because I missed home and I missed good food,” she reflects.

Since then, Gowardhan fell in love with food and made her way into the industry, and this is her third cookbook. She now deems it her “calling”, saying: “I knew food was something that was a leveler on every aspect of my life.

“When we did really well, my mother would say, ‘Can I make you something?’ If we were really upset she was like, ‘Let me cook for you’.”

Gowardhan also suspects some of it comes from her grandmother, who was an “avid cook”.

“My grandmother was the hostess with the mostess. In the 1950s in the city of Bombay, a lot of film stars and Bollywood film stars in India would actually come to my grandmother’s house to eat her food. To be a fly on the wall at my grandmother’s dinner parties…”

Gowardhan’s grandmother passed down these recipes, and her mother’s passion for food “gave us this effervescence for cooking and eating good food”, she adds.

After dedicating the past 20 or so years of her career to Indian food, there’s a major thing Gowardhan would like people to know about the cuisine.

“People tend to forget it’s actually a subcontinent. Because it’s a subcontinent, you realise there is so much more, and every community has so much more to say about the food they cook.

“Of course, it’s blurred boundaries as you go through every space, but I feel like every 20 or 30 kilometres you’re travelling, the food changes – because the crop changes, because the climate changes, because the soil changes. All of that makes a huge difference.”

So, when people ask her to sum up Indian food, Gowardhan says: “It’s like saying, ‘What is your favourite European food?’ Impossible.”

‘Tandoori Home Cooking’ by Maunika Gowardhan (Hardie Grant, £25).

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments