How Empress Josephine made Bordeaux fashionable

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.There wasn't a single bottle of Bordeaux in King Louis XVI's cellar, but 30 years later Napoleon's Empress Josephine had amassed a vast collection of luxury Bordeaux wines, launching a fashion that put Latour and Margaux on high society tables.

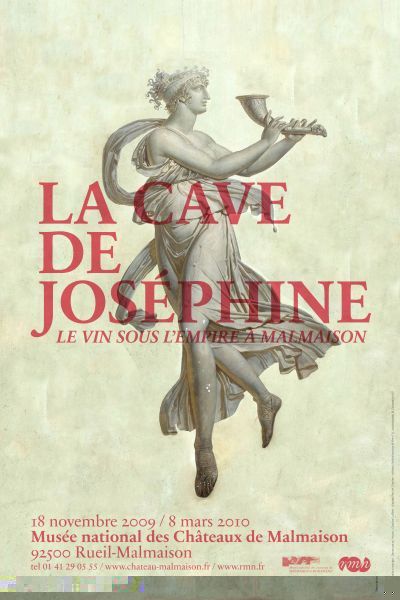

In a new exhibit, "Josephine's Cellar: Wine at Malmaison during the Empire", at the National Museum Chateau de Malmaison just outside Paris, visitors catch a rare glimpse of what was served at the Empress's table, and the innovations in wine production and trade during Napoleon's rule.

The hand-written inventory of Josephine's 13,000-bottle collection reveals a surprising diversity, as sophisticated as the exotic menagerie and gardens she created at Malmaison, her last residence.

While most of her contemporaries were drinking Burgundy, Champagne and sweet wines from the Mediterranean, Josephine filled her guests' glasses with Bordeaux, Cotes-du-Rhone and wines from as far away as South Africa.

Her cellar, "faithful to 18th century taste, really announces that of the 19th century," summed up Elisabeth Caude, the exhibit's curator.

Napoleon, on the other hand, had a penchant for the pinot noir of Chambertin, Burgundy, and watered down his wine, said the curator.

Josephine, raised in Martinique, also kept an impressive collection of rum - 332 bottles at the time of her death. She used the rum to make punch for her extravagant parties, adding sugar, tea, cinnamon and lemon.

Her Caribbean roots also influenced her taste in wine. Bordeaux, France's main port at the time, exported wine to the Caribbean. When she became Empress, members of her entourage had ties to Bordeaux's estates, notably Chateau Latour, and did their best to promote the wines to the Empress.

Meanwhile, England, fearing that France's anti-monarchist revolution might bring the guillotine across the Channel, enforced a crushing blockade on France's sea trade routes. Bordeaux winegrowers lost their most lucrative client, England, and turned to the domestic market, and the woman at the heart of high society.

Four decades later, Bordeaux wines were officially classified into five "growths" according to their commercial value for the 1855 Universal Exhibition. That classification became a way for consumers to judge quality and value, and remains for the most part relevant today.

But Josephine was well ahead of that trend. At the time of her death, 45 percent of her wine collection was Bordeaux. To have such an important stock of Bordeaux, at that time, demonstrates a "very confirmed particularism", according to curator Alain Pougetoux.

She owned remarkable quantities of the four wines that would be later classified as First Growths in 1855: Lafite, Latour, Margaux and Haut Brion, as well as sweet wines from Sauternes. One entry from the inventory of her cellar: "463 bottles of wine from Chateau Margaux, estimated 926 francs".

The exhibit also traces evolutions in table manners following the Revolution.

Fashionable hostesses adopted a Russian style service: for the first time, glasses were set with the place settings prior to the arrival of the guests, whereas before a valet had circulated with glasses and a carafe during the meal.

It was also a time of innovation that brought beautiful new things to the table: crystal. Up until then, the English had monopolized its production through a carefully guarded secret. Progress in French glassmaking opened the door to elegant glasses, stronger bottles and new forms.

The exhibit also displays many curiosities, like the escutcheons that once draped the necks of bottles. Labels were very rare at this time, and this was the only way to show what was in the bottle.

Not to be missed, several intriguing bottles, notably those of the Emperor. A bottle of Margaux Bel Air 1858 has this inscription on the glass ribbon seal, "Defendu d'en Laisser" - forbidden to leave any of it.

The exhibit runs from now until next March 8. It then travels to the Napoleon Museum in the Arenenberg Castle, Switerland, from April 10 to October 10, 2010, and then on to Rome at the Museo Napoleonico from October 2010 to February 28, 2011.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments