How a Buenos Aires shantytown food court helps bridge the social inclusion gap

‘Gastronomy can help construct bridges in marginal communities’. By Sorrel Moseley-Williams

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.On a wintery August Thursday in Buenos Aires, Elvia Tito left her home in Villa Rodrigo Bueno, a shantytown, and loaded up her car with pans, folding chairs, tables and cooking supplies.

It was business as usual for the Bolivian cook, who ran a lunchtime street food stall outside Cinar, a shipbuilding yard in the Argentine capital, selling milanesa (breaded cutlet) sandwiches to taxi drivers and dock workers.

But the following day marked a huge professional and personal change: Elvia started working from a converted shipping container restaurant – her first legal business – at the Patio Gastronómico Rodrigo Bueno, a brand-new outdoor food court located half a block from the villa where she’s lived in precarious housing with her three children since 2003.

It’s taken three years for the food court to come to fruition, and she never believed it would open.

“I didn’t have any hopes that the patio gastronómico would ever become reality – not until I signed the contract for the container the week before opening,” she says.

“But as this was a group effort [with seven other villa residents], I always thought that maybe, if we stuck together, something would eventually happen.”

Elvia had her doubts with good reason. Urbanising the shantytown – whose breeze-block houses have existed alongside skyscrapers in the southeast corner of swanky Puerto Madero barrio (neighbourhood) near the Costanera Sur park since 1998 – to create a brand-new legit barrio took the IVC city housing institute 10 years.

Besides moving families out of badly insulated housing without legal utilities into purpose-built apartment blocks, being able to socially incorporate many who have been in the margins of society has been paramount to fulfilling basic human needs in a country where poverty affects 34.5 per cent of the population, as Argentina’s Indec statistics agency reported earlier this year.

The food court project started as a pipe dream around three years ago, when gastronomically inclined NGO Pueblo Abierto was tasked by the IVC to create cultural content that would help villa residents transition from living in a slum to a bona fide neighbourhood.

Aiming to empower women from an array of backgrounds in Peru, Bolivia, Paraguay and Argentina, this seemingly simple task was rife with setbacks, says Delfina Magrane of Pueblo Abierto.

“The IVC didn’t have any funds for this content so we presented a project to the Ley de Mecenazgo, a grants scheme that donates money to cultural causes.

The problem was that gastronomy didn’t fall under Mecenazgo’s definition of culture. We had to present additional material explaining why food was a fundamental part of their ancestral culture before we could even get started,” she says.

Once Pueblo Abierto was finally allocated a portion of the awarded funds, little by little Delfina and NGO co-founder Carol Merea started working with those Rodrigo Bueno residents, both women and men, who were keen to learn more about gastronomy.

Many, like Elvia, already ran illegal street food carts or sold homemade food to neighbours, but had never undertaken formal training; Pueblo Abierto helped them to enrol in culinary and hygiene courses and workshops, also taking them to markets and restaurants to acquire wider experiences. “We also acted as residents’ representatives, helping them interact with the IVC,” adds Delfina.

Last December, for example, with Pueblo Abierto’s guidance, the villa’s more prominent cooks prepared a lunch with local celebrity chefs; all dined together in the shantytown, another way to motivate the entrepreneurs-in-waiting.

Of the 65 residents who initially signed up with Pueblo Abierto, just eight completed the courses, many struggling to find a balance between work and these extra-curricular activities. Today, seven run the five container restaurants in the Rodrigo Bueno food patio, given priority in return for their commitment to training.

Elvia shares the space – and the rent, making it her first legal business at the age of 45 – with Peruvian cook Julia Narvaéz, who prepares tempting desserts and cakes including the classic suspiro limeño for AR$150 (£1.95). Under the moniker Gelermala, Elvia prepares sopa de mani, a soup originating in Sucre, Bolivia, made from pureed peanuts, beef and potato that’s seasoned with saffron, cumin and ají amarillo (yellow chilli).

She slow-cooks the peanuts for two hours, prepares it in her cramped kitchen at home, just a few blocks from the patio; diners can see the villa from the food court. A filling bowl goes for AR$100 (£1.30).

All their dishes have to be approved by the court’s manager, so they don’t compete with the five private restaurants also located on-site. “I’m not allowed to cook my Bolivian burger, for example, which despite having the same name, is very different. The patty is made with minced beef as well as carrots, cumin, egg, parsley and garlic. It’s a bit frustrating and I hope they change the rules so I can make what I like,” she says.

At the Rincón de Sabores container, Paraguayan husband-and-wife team Antonio Benitez and Tomasa Peña make a lomito completo (steak sandwich) teamed with traditional Paraguayan sides such as chipa guazú (cheesy corn cake) and sopa paraguaya (corn bread).

Although business has been slow since opening two months ago, Tomasa notes that customers are interested in their dishes, because, despite the fact that more than half a million Paraguayans live in Buenos Aires, few restaurants specialising in this cuisine exist. “Paraguayans who come once usually return: we eat a lot of beef, corn and potatoes so it’s a taste of home for them.”

They used to run a small canteen in the villa, preparing milanesas to take away. But as they recently moved into one of the brand new apartments with 17-year-old daughter Melody, they’ve given up that enterprise. The upside, however, is they now run a family business that’s legal.

Tomasa adds: “Melody told us she wanted to work at McDonald’s but we said a better opportunity would be learning alongside us. What’s better than working together as a family? If she wants to go ahead and do that, so be it, but at least she’ll have learnt valuable skills.

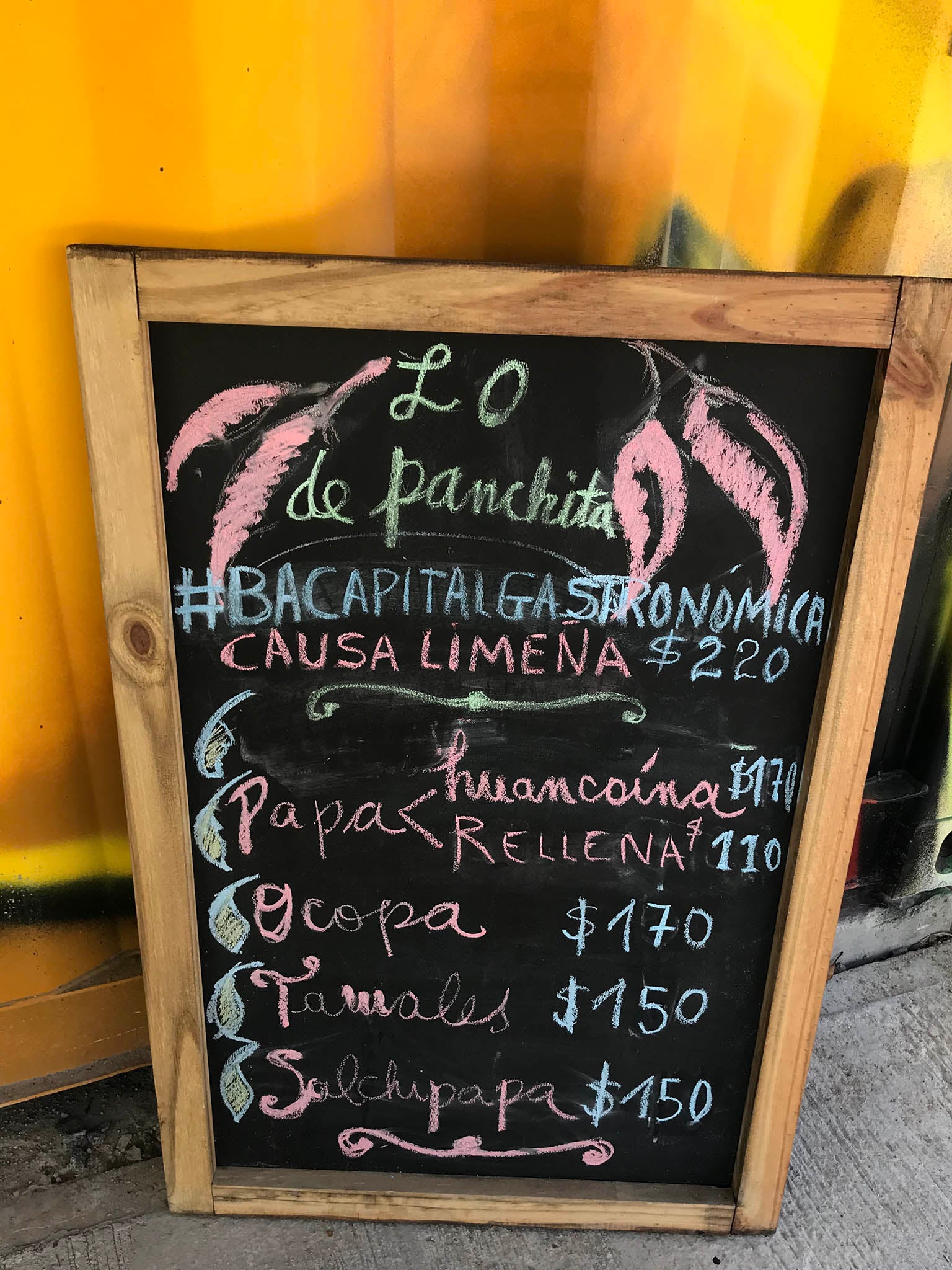

And at Lo de Panchita, 68-year-old Francisca ‘Panchita’ Latorre creates Peruvian classics such as salchipapas beef sausages and chips, and papas a la huancaína, potatoes slathered in a delicious yellow chile sauce with hard-boiled egg. One customer returns every week to sample a new dish, she says, because the food court represents the migrants who live in what is now officially called Barrio Rodrigo Bueno. “There’s such a mixture of food and cultures here, it’s impossible to try everything in a single day. This lady, in particular, will try a different dish each time – I love that,” she says.

The Rodrigo Bueno isn’t the only shantytown undergoing urbanisation that uses food as a positive tool.

Next year, the sprawling Villa 31 in Retiro neighbourhood, home to one of Buenos Aires’ busiest commuter train stations, will open a 30-stand food court and produce market, further proof that gastronomy can help construct bridges in marginal communities.

“I like being able to talk to people at the food court; I get to explain my dishes to customers,” says Elvia.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments