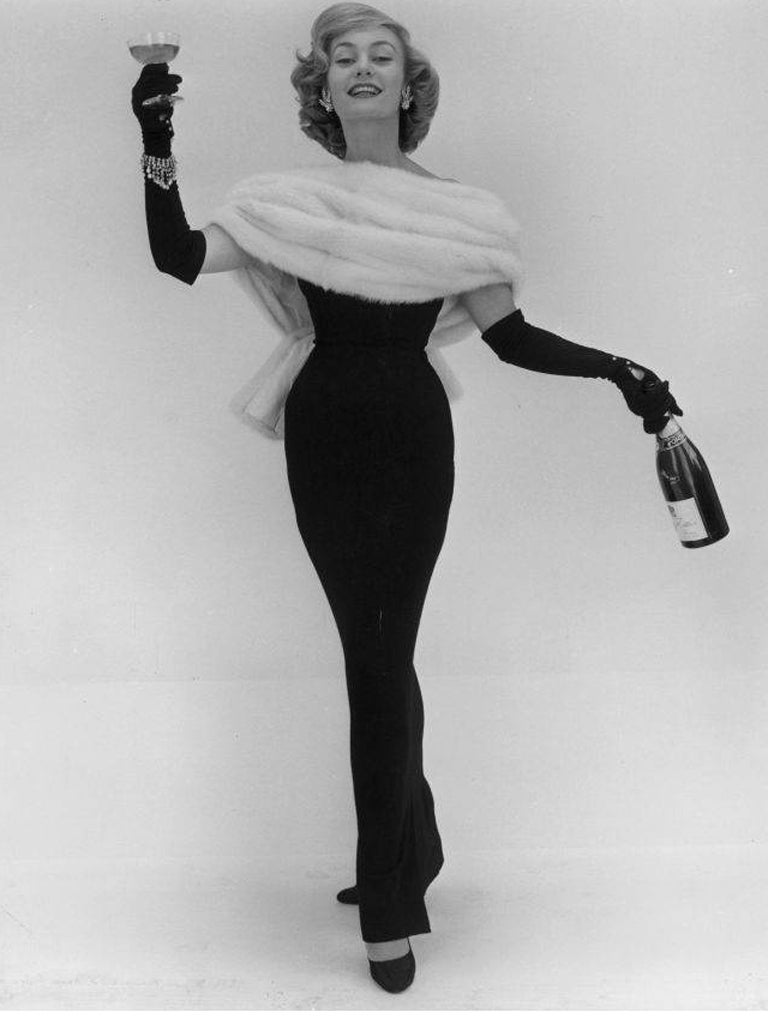

To health, prosperity and settled hearts! Raising a glass to the hearty toast

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Fans of A Christmas Carol will recall that the story ends with a slap-up dinner at the Cratchit household, a half-circle around the hearth and the salutation: "God bless us every one!" from the crippled-but-plucky Tiny Tim. Modern-day parishioners of the Bishop of London, Richard Chartres, know that his usual Christmas card salutation is "Health, prosperity and settled hearts." In Scotland, every household on New Year's Eve promises to "take a cup of kindness yet" in memory of long ago.

They're all toasts, a word redolent of comfort and warmth, which takes on more agreeable associations when it means clinking glasses (to frighten away the devil with the sound of bells) and drinking to the happiness of another. This Yuletide, it'll mostly mean a cry of "Cheers!", but it used to be a much more elaborate ritual. The tradition dates back to antiquity (Odysseus drinks to the health of Achilles in Homer's Odyssey), but it wasn't called "toasting" until the 17th century, when "wassailing" meant drinking people's health from a bowl containing ale, boiled with roasted apples, sugar, nutmeg and, amazingly, toast. No really: once, you toasted people with actual toast.

The figurative use of the word was defined in the Tatler of 1709 by Isaac Bickerstaff: "...the present honour which is done to the lady we mention in our liquor, who has ever since been called a toast." The toast became an excuse for after-dinner drinking. With no shortage of toast-worthy people (after you'd exhausted the company in the room, you could move on to "absent friends") and no need for actual conversation beyond calling names and drinking with loud huzzahs, it was a party game in which everyone could join. The 18th and early 19th centuries saw the rise of 15-course, heroically intoxicated, toast-tastic dinners. Women, although generally excluded, were the cause of the trouble. According to Paul Dickson's magisterial study, Toasts (1981), inebriated chaps would show the strength of their love by stabbing themselves in the arm and mingling their blood with the wine they drank to a lady. Competitions would break out, in which two gentlemen would each drink to their beloved's health, until one fell down.

Not everyone believed that "proposing a health" was an innocent celebration. Louis XIV forbade the drinking of toasts at his court. Temperance societies sprang up in America, aimed at banning the toast. In Ireland, the Bishop of Cork distributed pamphlets condemning the practice of drinking "a health" to the dead (he had a point). Nothing, though, could halt the march of toasting. The fad crossed the Atlantic. In the period up to the Civil War, toasts to the Union or the Confederate secession were commonplace at dinner. After the war, 13 toasts – one for each state in the Union – were drunk on the Fourth of July. Toasting became the pretext for, not drunken sentimentality about the laydeez, but political rhetoric: Benjamin Franklin was exceptionally eloquent with toasts that subtly subverted foreign dignitaries. By the 1920s, toasts were being written for every event from christening to funeral, magazines held toasting contests, books were published containing suitable inducements to quaff. But Prohibition put a sudden end to it in America, while in England it petered out during the war. In 1963, the poet John Pudney complained about "the decline of the eloquence and variety of the toast in the English language. The last two generations at least seem to find themselves embarrassed by the formality of toasting."

There have been signs, though, that it's back. Drinks manufacturers are keen to recall the tradition: the makers of Glenmorangie single malt are offering a "first-footing" package that includes a bottle of whisky, a lump of coal and the toast "Lang may yer lum reek" (ie long may your chimney smoke, an index of prosperity).

President Obama is an enthusiastic glass-raiser at state dinners, taking his cue from Ronald Reagan, an inveterate toaster (though we should forget the dinner in 1982, hosted by the President of Brazil, where Reagan proposed a toast to "the people of Bolivia").

And every year, half a million drinkers, alerted by Facebook and Twitter, try to break the world record for "the largest toast in history." So why not try a toast yourself this Christmas? My favourite of all time? It's Elaine's from Seinfeld: "Here's to those who wish us well and those who don't can go to hell."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments