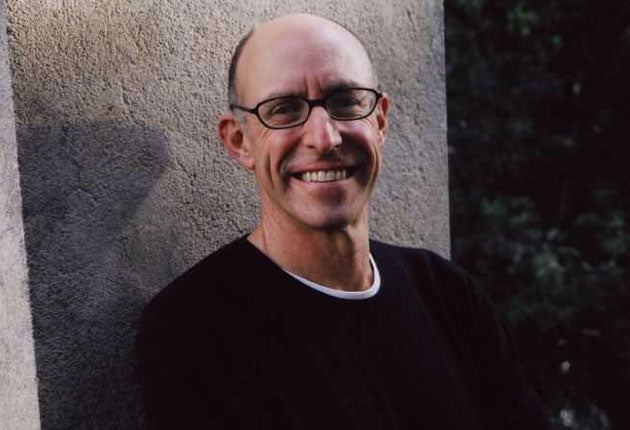

Michael Pollan's food manifesto

When did the wholesome act of enjoying a meal become so fraught with risk? Modern man has lost touch with what's on his plate, argues food writer Michael Pollan – and he'd do well to digest some simple lessons

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Eating in our time has become complicated – needlessly so, in my opinion. Most of us have come to rely on experts of one kind or another to tell us how to eat – doctors and diet books, media accounts of the latest findings in nutritional science, government advisories and food pyramids, the proliferating health claims on food packaging. We may not always heed these experts' advice, but their voices are in our heads every time we order from a menu or wheel down the aisle in the supermarket. Also in our heads today resides an astonishing amount of biochemistry. How odd it is that everybody now has at least a passing acquaintance with words like "antioxidant," "saturated fat," "omega-3 fatty acids," "carbohydrates," "polyphenols," "folic acid," "gluten," and "probiotics"? It's got to the point where we don't see foods any more but instead look right into them to the nutrients they contain (good and bad), and of course to the calories – all these invisible qualities in our food that, properly understood, supposedly hold the secret to eating well.

But, for all the scientific and pseudo-scientific food baggage we've taken on in recent years, we still don't know what we should be eating. Should we worry more about the fats or the carbohydrates? Then what about the "good" fats? Is it really true that this breakfast cereal will improve my son's focus at school or that other cereal will protect me from a heart attack? And when did eating a bowl of breakfast cereal become a therapeutic procedure? A few years ago, feeling as confused as everyone else, I set out to get to the bottom of a simple question: what should I eat? I'm not a nutrition expert or a scientist, just a curious journalist hoping to answer a straightforward question for myself and my family.

The deeper I delved into the confusing thicket of nutritional science, sorting through the long-running fats versus carbs wars, the fibre skirmishes and the raging dietary supplement debates, the simpler the picture gradually became. I learned that science knows a lot less about nutrition than you would expect – that in fact nutrition science is, to put it charitably, a very young science. Today it's approximately where surgery was in the year 1650 – very promising, and very interesting to watch, but are you ready to let them operate on you? I think I'll wait a while.

There are basically two important things you need to know about the links between diet and health, two facts that are not in dispute. All the contending parties in the nutrition wars agree on them. And these facts are sturdy enough that we can build a sensible diet upon them.

The first is that populations that eat a so-called western diet – generally defined as a diet consisting of lots of processed foods and meat, lots of added fat and sugar, lots of refined grains, lots of everything except vegetables, fruits and wholegrains – invariably suffer from high rates of the so-called Western diseases: obesity, type 2 diabetes. Eighty per cent of the cardiovascular diseases and more than a third of all cancers can be linked to this diet.

Secondly, there is no single ideal human diet; the human omnivore is exquisitely adapted to a wide range of different foods. And there is a third, very hopeful fact that flows from these two: people who get off the western diet see dramatic improvements in their health.

The selection of food rules below are less about the theory, history and science of eating than about our daily lives and practice. They are personal policies, designed to help you eat real food in moderation and, by doing so, substantially to get off the western diet. I deliberately avoid the vocabulary of nutrition or biochemistry, though in most cases there is scientific research to back them up.

Most of these rules I wrote, but many of them have no single author. They are pieces of food culture, sometimes ancient, that deserve our attention, because they can help us. I've collected these adages about eating from a wide variety of sources. I consulted folklorists and anthropologists, doctors, nurses, nutritionists, and dietitians, as well as a large number of grandmothers, and great-grandmothers. I solicited food rules from my readers and from audiences at conferences and speeches on three continents; I publicised a web address where people could email rules they had heard from their parents or others and had found personally helpful. Taken together, these rules comprise a kind of choral voice of popular food wisdom. My job has not been to create that wisdom so much as to curate and vet it. My wager is that that voice has as much or more to teach us, and to help us right our relationships to food, than the voices of science and industry and government.

Eat only foods that will eventually rot.

What does it mean for food to "go bad"? It usually means that the fungi and bacteria and insects and rodents with whom we compete for nutrients and calories got to it before we did. Food processing began as a way to extend the shelf life of food by protecting it from these competitors. This is often accomplished by making the food less appealing to them, by removing nutrients from it that attract competitors, or by removing other nutrients likely to turn rancid, such as omega-3 fatty acids. The more processed a food is, the longer the shelf life, and the less nutritious it typically is. Real food is alive—and therefore it should eventually die. (There are a few exceptions to this rule: for example, honey has a shelf life measured in centuries.)

Eat foods made from ingredients that you can picture in their raw state or growing in nature.

Read the ingredients on a packet of Pringles and imagine what those ingredients actually look like raw or in the places where they grow: you can't do it. This rule will keep all sorts of chemicals and food-like substances out of your diet.

Get out of the supermarket whenever you can.

You won't find any high-fructose corn syrup at the farmers' market. You also won't find any elaborately processed food products, any packages with long lists of unpronounceable ingredients or dubious health claims, anything microwaveable, or, perhaps best of all, any old food from far away. What you will find are fresh, wholefoods harvested at the peak of their taste and nutritional quality – precisely the kind your great-grandmother, or even your neolithic ancestors, would easily recognise as food. The kind that is alive and eventually will rot.

Eat only foods that have been cooked by humans.

If you're going to let others cook for you, you're much better off if they are other humans, rather than corporations. In general, corporations cook with too much salt, fat, and sugar, as well as with preservatives, colourings, and other biological novelties. They also aim for immortality in their food products. Note: while it is true that professional chefs are generally humans, they often cook with large amounts of salt, fat, and sugar too, so treat restaurant meals as special occasions. The following are a few useful variants on the humancooked-food rule.

Eat mostly plants, especially leaves.

Scientists may disagree on what's so good about plants – the antioxidants? the fibre? The omega-3 fatty acids? – but they do agree that they're probably really good for you and certainly can't hurt. There are scores of studies demonstrating that a diet rich in vegetables and fruits reduces the risk of dying from all the western diseases; in countries where people eat a pound or more of vegetables and fruits a day, the rate of cancer is half what it is in the United States.

Also, by eating a diet that is primarily plant based, you'll be consuming far fewer calories, since plant foods – with the exception of seeds, including grains and nuts – are typically less "energy dense" than the other things you eat. (And consuming fewer calories protects against many chronic diseases.) Vegetarians are notably healthier than carnivores, and they live longer.

Treat meat as a flavouring or special occasion food.

While it's true that vegetarians are generally healthier than carnivores, that doesn't mean you need to eliminate meat from your diet if you like it. Meat, which humans have been eating and relishing for a very long time, is nourishing food, which is why I suggest "mostly" plants, not "only". It turns out that near vegetarians, or "flexitarians" – people who eat meat a couple of times a week – are just as healthy as vegetarians. There is evidence that the more meat there is in your diet – red meat in particular – the greater your risk of heart disease and cancer.

Why? It could be its saturated fat, or its specific type of protein, or the simple fact that all that meat is pushing plants off the plate. Thomas Jefferson was probably on to something when he recommended a mostly plant-based diet that uses meat chiefly as a "flavour principle".

"Eating what stands on one leg [mushrooms and plant foods] is better than eating what stands on two legs [fowl], which is better than eating that which stands on four legs [cows, pigs, and other mammals]."

This Chinese proverb offers a good summary of traditional wisdom regarding the relative healthiness of different kinds of food, though it inexplicably leaves out the very healthy and entirely legless fish.

Eat your colours.

The idea that a healthy plate of food will feature several different colours is a good example of an old wives' tale about food that turns out to be good science too. The colours of many vegetables reflect the different antioxidant phytochemicals they contain – anthocyanins, polyphenols, flavonoids, carotenoids.

Many of these chemicals help protect against chronic diseases, but each in a slightly different way, so the best protection comes from a diet containing as many different phytochemicals as possible.

Eat animals that have themselves eaten well.

The diet of the animals we eat strongly influences the nutritional quality, and healthfulness, of the food we get from them, whether it is meat or milk or eggs. This should be self-evident, yet it is a truth routinely overlooked by the industrial food chain in its quest to produce vast quantities of cheap animal protein.

That quest has changed the diet of most of our food animals in ways that have often damaged their health and healthfulness. We feed animals a high-energy diet of grain to make them grow quickly, even in the case of ruminants that have evolved to eat grass. But even food animals that can tolerate grain are much healthier when they have access to green plants – and so, it turns out, are their meat and eggs.

The food from these animals will contain much healthier types of fat (more omega-3s, less omega-6s) as well as appreciably higher levels of vitamins and antioxidants. (For the same reason, meat from wild animals is particularly nutritious.) It's worth looking for pastured animal foods in the market – and paying the premium prices they typically command if you can.

Sweeten and salt your food yourself.

Whether soups or cereals or soft drinks, foods and beverages that have been prepared by corporations contain far higher levels of salt and sugar than any ordinary human would ever add – even a child. By sweetening and salting these foods yourself, you'll make them to your taste, and you will find you're consuming a fraction as much sugar and salt as you otherwise would.

"The whiter the bread, the sooner you'll be dead."

This rather blunt bit of cross-cultural grandmotherly advice (passed down from both Jewish and Italian grandmothers) suggests that the health risks of white flour have been popularly recognised for many years. As far as the body is concerned, white flour is not much different from sugar.

Unless supplemented, it offers none of the good things (fibre, B vitamins, healthy fats) in wholegrains – it's little more than a shot of glucose. Large spikes of glucose are inflammatory and wreak havoc on our insulin metabolism. Eat wholegrains and minimise your consumption of white flour. Recent research indicates that the grandmothers who lived by this rule were right: people who eat lots of wholegrains tend to be healthier and to live longer.

Have a glass of wine with dinner.

Wine may not be the magic bullet in the French or Mediterranean diet, but it does seem to be an integral part of these dietary patterns.

There is now considerable scientific evidence for the health benefits of alcohol to go with a few centuries of traditional belief and anecdotal evidence. Mindful of the social and health effects of alcoholism, public health authorities are loath to recommend drinking, but the fact is that people who drink moderately and regularly live longer and suffer considerably less heart disease than teetotallers.

Alcohol of any kind appears to reduce the risk of heart disease, but the polyphenols in red wine (resveratrol in particular) may have unique protective qualities. Most experts recommend no more than two drinks a day for men, one for women. Also, the health benefits of alcohol may depend as much on the pattern of drinking as on the amount: drinking a little every day is better than drinking a lot at the weekends, and drinking with food is better than drinking without it.

Someday science may figure out the complex synergies at work in a traditional diet that includes wine, but until then we can marvel at its accumulated wisdom – and raise a glass to paradox.

Stop eating before you're full.

Nowadays we think it is normal and right to eat until you are full, but many cultures, however, advise stopping well before that point is reached. The Japanese have a saying – "hara hachi bu" – counselling people to stop eating when they are 80 per cent full. The Ayurvedic tradition in India advises eating until you are 75 per cent full; the Chinese specify 70 per cent, and the prophet Mohamed described a full belly as one that contained "N food and N liquid and N air" – that is, nothing. (Note the relatively narrow range specified in all this advice: somewhere between 70 and 80 per cent of capacity. Take your pick.)

There's also a German expression that says: "You need to tie off the sack before it gets completely full." And how many of us have grandparents who talk of "leaving the table a little bit hungry"? Here again the French may have something to teach us. To say "I'm hungry" in French you say "J'ai faim" ("I have hunger") and when you are finished, you do not say that you are full, but "Je n'ai plus faim" ("I have no more hunger"). That is a completely different way of thinking about satiety. So: ask yourself not, "Am I full?" but, "Is my hunger gone?" That moment will arrive several bites sooner.

Do all your eating at a table.

No, a desk is not a table. If we eat while we're working, or while watching TV or driving, we eat mindlessly – and, as a result, eat a lot more than we would if we were eating at a table, paying attention to what we're doing. This phenomenon can be tested (and put to good use). Place a child in front of a television set and place a bowl of fresh vegetables in front of him or her. The child will eat everything in the bowl, often even vegetables he or she doesn't ordinarily touch, without noticing what's going on. Which suggests an exception to the rule: when eating somewhere other than at a table, stick to fruits and vegetables.

Break the rules once in a while.

Obsessing over food rules is bad for your happiness, and probably for your health too. Our experience over the past few decades suggests that dieting and worrying too much about nutrition has made us no healthier or slimmer; cultivating a relaxed attitude toward food is important. There will be special occasions when you will want to throw these rules out the window. All will not be lost. What matters is not the special occasion but the everyday practice – the default habits that govern your eating on a typical day. "All things in moderation," it is often said, but we should never forget the wise addendum, sometimes attributed to Oscar Wilde: "including moderation".

This is an edited extract from 'Food Rules' by Michael Pollan, published in paperback by Penguin (£5.99). To order a copy for the special price of £5.50 (free P&P) call Independent Books Direct on 08430 600 030, or visit www.independentbooksdirect.co.uk

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments