The 11 rules for what makes the perfect restaurant according to Britain’s greatest restaurateur

The man who brought us The Ivy, Caprice and The Wolseley is back with three new must-go restaurants. Richard Godwin meets the King himself, Jeremy King that is, to find out what it really takes to make a dining room truly iconic

I was on my way to meet the restaurateur Jeremy King at his latest venue, The Park – a modern American diner on the north edge of Hyde Park. What had been a refreshing drizzle became a full-on downpour and I was a damp, sweaty mess. Then the windows of The Park came into view: an amber glow of civilisation, the ideal antidote to a crap London summer.

Inside, I was shown to a reassuringly expensive-feeling booth where I ordered a Cobb salad from a menu exclusively composed of things I wanted to eat: shrimp cocktail, chicken milanese, lobster rolls, pistachio tiramisu. It was delightful.

Everything was delightful, in fact. The weight of the cutlery, the tang of the tomato, the Le Corbusier lithographs on the walls – and the sight of King himself, ghosting into view in a dark grey suit with a dark blue paisley tie.

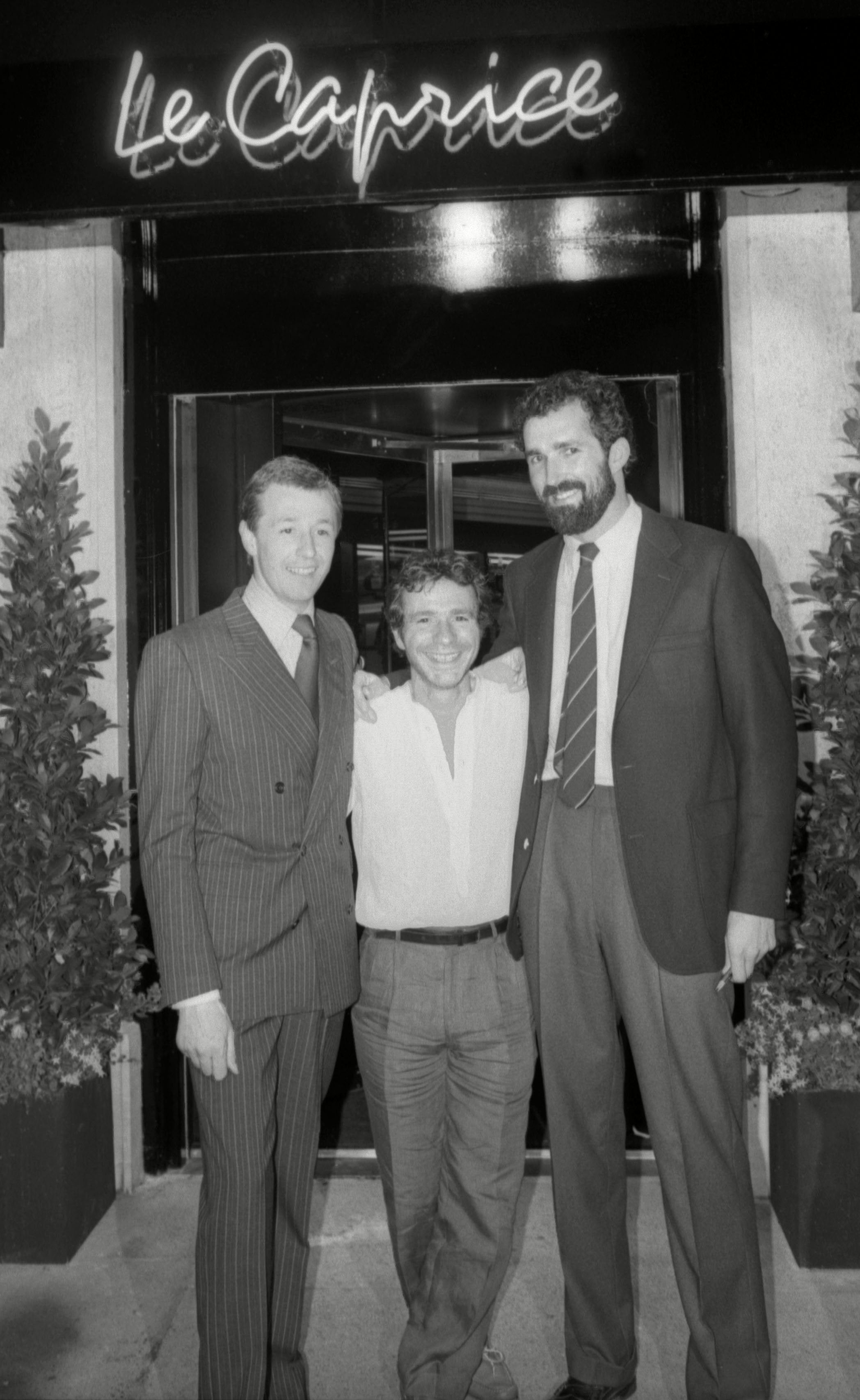

King inspires rare devotion for a restaurateur: Lucian Freud painted him; Harold Pinter based a character on him; Paul Smith personally designed his cufflinks. The Ivy, J Sheekey, The Wolseley, The Delaunay, Brasserie Zedel, Colbert were all instant institutions, at the centre of London social life. Dating back to Le Caprice in 1981, his restaurants are as close to perfect as restaurants can be.

King’s Who’s Who entry lists “solitude” among his hobbies. “I’m actually very shy and introverted. I’ve had to learn not to be,” he tells me, adding he only chose a career in hospitality on the roll of a dice in 1975, turning down a place at Cambridge to read economics. “I regret that every week, pretty much,” he smiles.

But it’s fair to say that no one else does. And now, at 70, King is gambling again with three new restaurants. In March, he opened Arlington on the site of the old Caprice. Next year, we will see what he has done with the venerable Simpsons in the Strand. And now we have The Park, already described by one critic as “heaven’s own refectory”.

So what, I want to know, is the secret to the perfect restaurant?

1. Feel the bones of the building

When King first walked into the former car showroom that would become the Wolseley, he immediately sensed what kind of restaurant would work there. “It was screaming out to be a Grand Café-type brasserie with that European feel.”

The Park, however, is the first of King’s restaurants to be purpose-built in a brand new building – the Park Modern luxury residential development in Queensway – which called for a new approach.

“When I first walked in, it was a concrete shell with the size not even determined and large vinyls on the window. But even so, I could feel what the light would be. Here we are on a very dark, rainy day and yet it still feels very light.”

The grand, modern, parkside location put him in mind more of New York than London, which in turn made him think of Philip Johnson’s classic design for The Four Seasons in the Seagrams building, “one of the great restaurants in true harmony with the building.” And so he began thinking of how to do a modern American grand café – a New World brasserie – in London.

2. Think of a restaurant as a book

King wanted to be a writer before he wanted to become a restaurateur – indeed, growing up in Burnham-on-Sea (with a mother who was a “terrible cook”), he says it was literature rather than any actual visits to restaurants that prompted his interest in food.

You can sense the frustrated novelist in the stories he creates for his restaurants. When he opened Colbert on Sloane Square in 2012, he dreamed up an entire life story for the proprietor, a French former waiter who fled Paris in the 1920s. “I imagined he worked somewhere like Les Deux Magots and he got run out of town because he’d seduced the proprietor’s daughter,” he says. “So he went to Chelsea which of course was really poor back in the 1920s and opened a bar which is the first room in Colbert.”

There are three different rooms in Colbert all designed to look like they had been added in subsequent eras. “If you look, each room has a different décor, a different floor, but they all hang together.”

King also knows his restaurant history. The reason old restaurants tend to feel much grander than new restaurants is due to the Landlord and Tenant Act 1954, which gave restaurateurs security of tenure with leases as long as 25 years. When there was no security a lot of restaurants in London were cheaply done and a little gimmicky – the precise opposite of what King aims to create.

The carpet, the wood panelling, the booths of The Park all feel lighter than the brass of the Wolseley or Delauney, but the overall feeling is one of permanence. “Could this be here in 50 years’ time? That’s my thinking. Let’s try to create a modern classic. That starts to dictate everything that goes through this place, from the art to the cutlery. I wanted it to feel rich and cosy.”

3. Capture a child’s excitement

The all-day menu combines the childish excitement of the diner (there are Chicago-style hotdogs; shrimp cocktails; ice cream cookie sandwiches) with more grown-up pleasures (scallops ceviche; an artichoke, butter bean and ricotta salad that is King’s personal favourite).

It’s printed on a large-format card, accented in cool turquoise and red, so you can take in the whole thing in one go. It’s extremely hard to imagine that anyone, from a child on a birthday treat to one of King’s longer-standing customers, would not be excited by something here.

The cocktails are rather good too, again leaning in an Italian/American direction. Think: palomas, pisco sours, as well as dirty martinis, plus a lovely bitterish spritz called the Rose Gray, named in honour of the late River Café co-founder – a classy touch.

4. But never scream for attention

“I think a lot of what often happens in restaurants is that everybody starts to try and outdo each other with more gimmicks,” says King. “My belief is that great design never screams attention, but it withstands scrutiny. You should walk in and say: gosh, this feels good. You’re not forced to contemplate why. But if you do, you might notice the details.”

Those details require quite careful thought: King has, for example, designed the font for The Park, just as he did for The Ivy back in the day. In most restaurants, you will find seating that can be reconfigured. Here, the booths are immovable – reminiscent of a diner but much more indulgent. “I like things to be a bit different.”

5. Curate like a gallerist

King is a connoisseur and the art on the walls is naturally, entirely of a piece with the modernist, architectural aesthetic. Each of the booths is looked over by a lithograph by the Swiss-French architect, Le Corbusier. Downstairs, there are portraits by Horst P Horst, the German-American fashion photographer who captured the beautiful people of New York in the 1940s and 1950s.

Above our table is a cool, evocative print by the mid-century American artist Alex Katz. “It’s modern but not aggressive,” says King. “It doesn’t really feel like London around here, so that’s why I went in that direction.”

6. Know a knife and fork is never just a knife and fork

That’s a direct borrow from the Four Seasons in New York. “I remember taking a photograph of this fork in New York a long time ago and thinking: I can use that one day.”

The fork is robust, heavy and feels expensive – like something one can imagine Don Draper using to spear at steak. The salt and pepper pots, similarly, could be used as dumbbells – all adding to a feeling of permanence.

7. And a glass is never just a glass

King always keeps his glassware extremely thin – a minor obsession. “If you go to a cheap restaurant you’ll probably have a Paris goblet on the table. It has a thick rim and it won’t chip but it’s not so nice to drink wine from.” The thin wine glasses chip more often so need replacing. But the breakage cost, he feels, is worth it for the first taste of the wine.

And those pleasingly thin glasses are etched with three parallel lines circling just below the rim. The simple design motif is echoed all around the restaurant, from the menu (which is headed by those three lines) to the champagne buckets, pepper pots and plates.

Within the interior, it is echoed by the heavy, slanted wooden slats that run down the windows. These are known as “louvers”. They are made from the same African limba wood as the rest of the restaurant fittings and they add to the feel of cosiness.

“I didn’t want to have a cafe curtain – that would be much earlier – but I didn’t want it to be entirely open and vulnerable to the street. So this gives a bit of psychological distance from the street. It’s detailing. We could have left it off and saved a lot of money. But I like the indulgence.”

8. Set the lighting

“I wanted lighting that wasn’t harsh and white but warm. And I wanted it to have a good impact from the street – that’s important.” The bulbs are all encased in lozenges that diffuse the light, a twist on the globes that would have been used in mid-century New York.

9. Pay attention to your poorest customers

King professes himself a fervent egalitarian. That might seem a bit rich for a man who dresses bespoke, drives a vintage Bristol and once went go-karting with Princess Diana. But his own upbringing was anything but grand, he stresses – and what makes a restaurant interesting is the social mix, he says. “That’s what makes a city interesting. Everyone should have the same opportunity to be part of it. In a restaurant, often, the most interesting people are the least affluent. You have to create restaurants where people can be equal within the place and aren’t looked down upon because they’re not spending.”

One of King’s proudest achievements was Brasserie Zédel, the huge all-day brasserie off Piccadilly Circus, where a three-course prix-fixe remains less than £20. The Park isn’t cheap but neither is it outrageous in a city where £20+ martinis are now fairly commonplace.

My salad was £12.50. Mains begin at £17.50 (but run up to £43). Cocktails are £12-£15 with a little list of £7 “sharpeners” (such as the long-neglected apéritif, the chrysanthemum: dry vermouth, Bénédictine, splash of absinthe). Still, King believes in giving people the “opportunity to spend” – hence the wine list runs up to a £2,500 bottle of Harlan Estate Californian red.

10. Don’t have a dress code

“I wear a suit and tie – but I abhor dress codes,” says King. “It’s so pretentious. I would guess that in 45 years of being a proprietor, 85 per cent of the serious problems I’ve had in restaurants have been caused by men in suits and ties.”

11. Walk in your customers’ shoes. Every day

The best restaurants, King feels strongly, bear the imprint of their proprietor – not their investors. That means being present. Formerly, he would stop by all of his restaurants in a day (breakfast at the Wolseley, afternoon tea at Fischer’s, etc). For the moment his schedule is divided between Arlington, The Park and Simpsons (currently a building site). “If we run restaurants from the boardroom, we end up making decisions that are not good for the customers.”

And it’s also good for him too. “The secret of happiness is to do the things in life you want to do – not what you feel you should do.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments