Conflict Kitchen: how food can unite us all

A series of pop-ups is serving up more than just supper, with conflict resolution and peace the main topic of dinner-party discussion

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.There is a universal language to sharing a meal. Well, that’s not strictly true. In China, it’s considered impolite to completely clear your plate (it implies your host hasn’t given you enough to eat), while in India it’s rude not to. In Japan, it’s seen as a sign of appreciation to loudly slurp your soup. In Korea, you mustn’t even raise your spoon until the oldest person has taken the first bite. And in Portugal it’s the height of bad manners to ask for salt and pepper - it suggests your host has not seasoned the meal enough.

But, customs aside, all cultures have certain things in common at mealtimes. Sharing food and playing host is an important part of society, and the bulk of social events and celebrations involve some meal or foodstuff. Christmas, Easter, birthdays, Passover, Eid, Thanksgiving - the list is endless. At home, most people socialise over lunch or dinner, chide their children for not sitting at the table for a proper breakfast, and spend hours perfecting their Sunday roast. Mealtimes traditionally allow for a forum - discussion of how your day has been, sealing a business deal or sharing important gossip over a pizza and bottle of wine. The very notion of “breaking bread” with someone suggests dialogue, communication and peace.

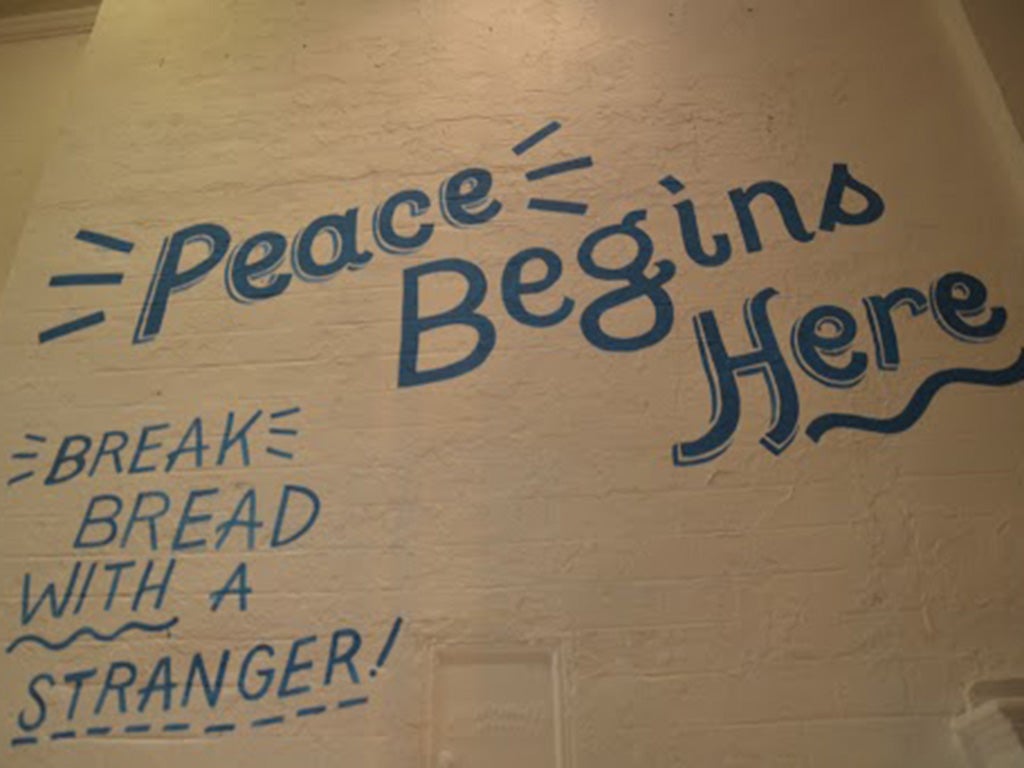

Peace is at the heart of a new series of supperclubs taking place in London this September. Conflict Kitchen London aims to show how food can unite and inform, with female chefs providing cuisine from three areas of conflict: Burma, Jordan and Peru. It is part of the Talking Peace Festival, a month-long series of events hosted by International Alert to celebrate peace and the power of words in resolving conflicts.

At the supperclubs, cue cards are left on the table to provoke discussion, and the host, organiser Phil Champain, will give a brief introduction to the evening. There is plenty of food for thought, if you will excuse the pun. In Burma, after years of struggle for the democracy from the ruling junta, the country is starting to see progress, but with a long way to go. In Peru, the booming mining industry is putting the future of the country’s indigenous people in doubt. And in Jordan, it stands in a precarious position in the heart of the Middle East as it struggles to cope with the influx of refugees from bordering Israel, Iraq and Syria.

Champain was partly inspired to set up Conflict Kitchen London by a US restaurant of the same name, which serves food from regions that America is in conflict with. “I thought it was a great way to provoke discussion - the art of talking and listening is often accompanied by food,” he said. “These events increase awareness of countries that are not in the headlines but still going through periods of transition. And the reaction has been even more positive than I expected, with people becoming really engaged in the informal setting.”

Champain is not the first to use food as a way of uniting people. In their bestselling cookbook Jerusalem, Yotam Ottolenghi and Sami Tamimi featured recipes are loosely inspired by the city, with influences from Christian, Muslim and Jewish cooks who live there. Ottolenghi grew up in the Jewish west of the city, Tamimi in the Arab east, and they controversially make reference in the book of how they are trying to harmonise both cultures through their collection of recipes. It is obviously a subject close to Ottolenghi’s heart, and he was one of the chefs who donated recipes for Conflict Kitchen London’s rooftop supperclubs this weekend to mark the International Day of Peace.

Burmese-born chef and artist Debbie Riehl ran the first of the three supper-club series, and encouraging all diners to strike up conversations about conflict and the prospects for peace in the country.

After a string of nights cooking for 50-plus diners, she is tired and footsore, but exhilarated. “The atmosphere was electric - both in the kitchen and dining room,” she said. “I’m so honoured to be part of this. All I do is feed people, but to see the conversation and engagement is brilliant.”

Conflict Kitchen London’s pop-up was only the second dedicated Burmese restaurant in Europe. Although the cuisine may be lesser known, it is delicious and fun - with coconut milk-laced curries and succulently sweet mango desserts. Perhaps, though, there is more knowledge of the troubles the country has faced than of its delicacies. Now, as it is emerging slowly from decades of military rule with the hope of a new democracy, dialogue is more important than ever.

“The borders have been closed for so long that people don’t have much knowledge about the food,” says Riehl. “My only real connection to Burma was through cooking - I grew up with my parents cooking traditional dishes, and cooked for my friends when I got older. When they started asking about Burmese restaurants and I realised how few there were, I decided to start running supperclubs - in my home at first for 14 people, and then bigger one-off events.

“I went to Burma last year - after an absence of almost 50. I think that was when I became more aware of the difficulties on the ground. When I was approached to take part in Conscious Kitchen London, I thought it was a wonderful way to help make a difference, using food as a vehicle for discussion. If the 50 people from last night each go away and talk to 10 friends about Burma, then hopefully it will have created a small difference.”

The ‘ripple effect’ notion is one being employed by charities and NGOs more and more, as people become fatigued with loudhailers, leaflets and hundreds of different organisations clamouring for attention. With something like a supperclub, many come for the food, but leave with a deeper understanding of and interest in the country.

“It’s a more palatable way of getting information - if you’ll excuse the pun,” says Riehl. “We don’t want to club you over the head with the message, just invite you to sit down with us, share some food and join the discussion.”

Conflict Kitchen London runs until 27 September. www.talkingpeacefestival.org/conflict-kitchen

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments