Fairtrade Fortnight: How the gift of coffee is empowering women in Kenya

Ahead of the #SheDeserves living wage campaign launching for Fairtrade Fortnight, Lizzie Rivera travels to Kenya to learn about the Women in Coffee project that’s giving female farmers grounds for hope

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.This morning I watched the sky get lighter over London rooftops – you could hardly call it a sunrise – with a cup of my prized “Zawadi” coffee. It is speciality AA grade coffee, considered some of the finest in the world. It has notes of milk chocolate and orange blossom. But most importantly, it was farmed exclusively by women.

I brought the coffee more than 6,500 miles to London, from the heights of Kenya’s Nandi Hills.

The altitude and steep inclines of Nandi County are mainly known for being the “cradle land of Kenyan running”, the birthplace of many Olympians including Pamela Jelimo, the first Kenyan woman to win an Olympic gold medal in 2008 in Beijing.

The rich volcanic soils are also ideal for growing tea, with estates creating neat, lush and green vistas as far as the eye can see.

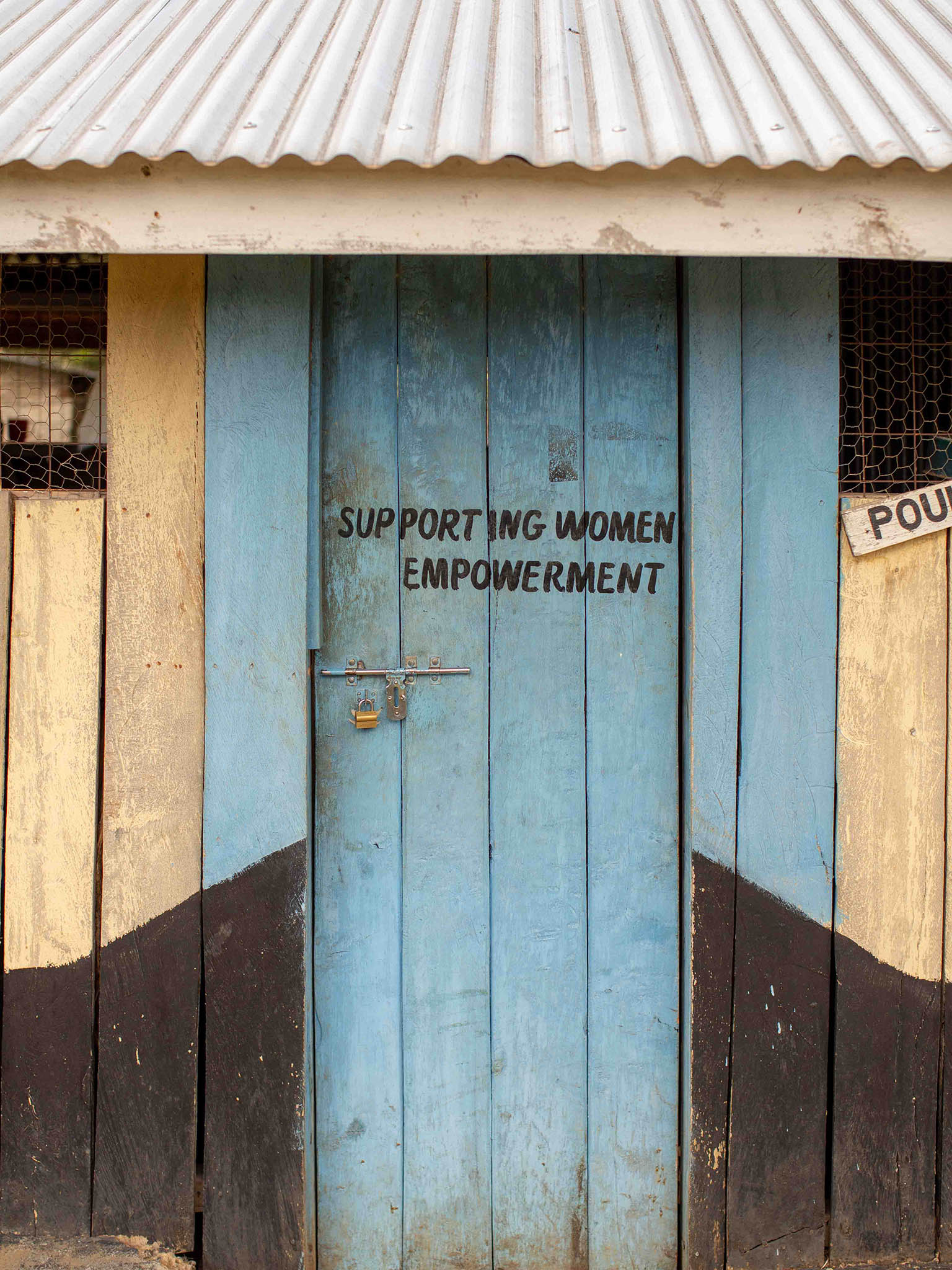

But the area is now attracting attention for another reason – its female coffee farmers. Zawadi means gift in Swahili, and the name represents the coffee created from bushes “gifted” to wives by their husbands as part of a pioneering Women in Coffee project.

Kenya produces just six per cent of the world’s coffee and Zawadi coffee makes up a tiny proportion of that, but it’s significant because in rural Kenya the culture is only just starting to shift to allow women to own their own land and coffee bushes.

The road to get to this point has been as long and bumpy as those leading to the hilltop villages of these farmers and there is still a long way to go in achieving true independence and equality. But these inspiring women were born in terrain that’s the ideal training ground to run marathons – and they’ve only just left the starting line.

Grounds for change

“Women in Coffee has changed my status from beggar to planner,” says Rhoda Biy, 50, mother to six children, from Kibukwo Farmers Cooperative Society (FCS).

It’s hard to listen to the backstories of the women who have been given a proportion of their husbands coffee bushes so they can earn their own incomes rather than work for free in the home and the fields.

Even now their days start around 5am and one confesses they don’t always end at 10pm once in bed, because they have a “responsibility to please their husband”.

Spill the beans: Coffee in numbers

• Around 80 per cent of the world’s coffee is produced in developing countries by 25 million small holders with less than 10 hectares of land

• Many coffee farmers live on less than $2 (£1.50) a day

• Globally, five corporations control around 50 per cent of the roasting and marketing of coffee (Kraft, Nestle, Sara Lee, Proctor & Gamble, Tchibo)

• In the UK we drink 55 million cups of coffee a day

But at least now they have their own income and don’t have to beg for money.

“Money for what?,” I ask. “For clothes and shoes?”

No – for food for their children and school fees. Even for the most audacious of wives sanitary protection remains a taboo subject.

But it’s also impossible not to be infected by the positive energy from both the men and the women we meet, who are working more closely together than ever and who are all now reaping the benefits of what they sow.

Conscious coffee

Although the women we meet typically carry out an estimated 70 per cent of the work in the home and on the farms, until recently it was only the men who received payment once the coffee cherries were processed at the mill. At which point it was not uncommon for them to disappear until the majority of the cash was spent – unless the wives were able to wrestle some money off their husbands first.

“You could hear the quarrels when the men come to collect the money and women had to wait outside. Our cooperative used to employ an armed policeman, which is quite common,” says secretary manager of Kibukwo cooperative, Shadrack Suge.

“Actually, it was the men who used to pay for security cover.”

This is a common story throughout the region. With little incentive to add to their unrewarded workload, women gradually stopped tending to the coffee bushes. Production suffered, which affected the whole community, including the profits at the mill where the coffee cherries are processed into beans. So, Women in Coffee was born.

“We discussed how to get rid of this embarrassment where the main breadwinner was leaving his wife and children hungry and not appreciating the work the women were doing,” says the chairman of neighbouring Kabng’etuny Farmers Coffee Cooperative Society, Samson Koskei.

He came up with the idea that maybe men could part with some of their coffee bushes in July 2012.

“The first meeting didn’t go well because we were asking the male farmers to transfer their assets to women,” he says. “One said ‘you cannot disinherit me when I’m still alive’.”

How Fairtrade works

Fairtrade sets a minimum price that farmer organisations are paid for coffee – regardless of its price on the stock exchange

Farmers receive an additional Fairtrade Premium – 25 per cent of this must be used to enhance productivity and quality

Fairtrade provides technical support and helps farmers to build better relationships with buyers

The men were also fearful their wives would squander their earnings or run off with their new-found independence.

So, Koskei and a handful of others gave their wives coffee bushes to set an example. This meant their wives could register as members of cooperative societies, open bank accounts and receive a direct income from selling coffee. That same year, they saw men and women line up together to get their earnings for the first time ever.

The minimum number of bushes to be gifted is still set at 50 as men own an average of 300-400 each. But the project has been a phenomenal success and there are now more than 500 smallholder women coffee farmers who own an average of 250 coffee bushes each, according to the latest Fairtrade reports.

Incredibly, more than 70 per cent of the coffee produced is now of premium quality, up from 25 per cent when the project began. The women are also producing almost double the amount of coffee cherries per bush – and this increase in productivity continues to rise.

Trained, inspired and now running their own Women in Coffee boards, the leadership tables at the cooperatives’ head offices reveal some women with fewer bushes than men are harvesting more coffee cherries in total. This has led to healthy competition between the sexes – inspiring men to rise to the challenge.

Even more importantly, it’s changing the dynamics within the family.

“Before we men spent our spare income on soda, or we lent it to friends, which meant that our children’s school fees were not covered,” says chairman of Kibukwo cooperative, Haron Biy.

“But we quickly learned that if you give your wife 1,000 Kenyan Shilling (75p), she knows how to manage that money properly. We know we have to change and learn from our wives.

“Women are much more productive and go the extra mile.”

Four great fair trade coffee brands

Percol: Fairtrade, carbon neutral and some ranges now come in compostable packaging - making them the first coffee brand to receive the Plastic Free Trust Mark

Cafedirect: Invests 50 per cent of profits into Producers Direct - a UK charity run by farmers, for farmers, developing innovative solutions to the challenges they face

CRU Kafe: The Fairtrade and organic alternative to Nespresso capsules

Union: An independent “trade, not aid” model. In 2017 Union paid on average over 50 per cent more than the minimum Fairtrade price. They work directly with the farmers to improve the quality of the coffee and the farmers quality of life

Every farmer tells a similar story. When one confessed to his wife they were going to have to sell the family cow, their source of milk, to pay for their daughter’s school fees, she was able to cover them and keep the cow.

Another admits: “I fear my children will say it’s only their mother paying their school fees, so I’m motivated to pay.”

Equal shot

Fairtrade has been essential to the success of Women in Coffee. Primarily for its very existence, as the foundation has always pushed for greater equality in the cooperatives they work with.

Practically speaking, they continue to teach the women best practice when it comes to farming, providing the tools that enables them to thrive.

Optimism radiates from these women, and I lose count of the times they declare themselves “empowered”.

Yet, there are many more injustices and challenges to overcome, not least because male and female coffee farmers are at the bottom of the supply chain.

Coffee is the second most traded commodity in the world (behind crude oil) and it’s reported to be worth $100bn (£75bn) on the New York Stock Exchange.

It’s nowhere near as valuable for the farmers though, who typically receive less than 10 per cent of the retail price of a pack of coffee once all of the middlemen have taken their cut.

We did the maths at the Kibukwo cooperative and worked out that coffee farming brings in around 80p per day. As such, some of the farmers have never tasted the coffee they produce and most can rarely afford to drink it.

On top of this, production is at the mercy of the weather, and farmers – male and female – simply don’t have the means to invest in the infrastructure to protect themselves or their crops against climate change.

Even if you’re sceptical about the effectiveness of certifications like Fairtrade, the Women in Coffee project is a phenomenal example of the far reaching benefits of long-term vision and investment in people.

Zawadi coffee is only available to buy in Kenya, for now. But, as consumers, the greatest power we have to help women the world over support themselves is to make sure we’re buying coffee that doesn’t exploit farmers but empowers them, by choosing Fairtrade or similar. That’s a gift we can give every single day.

And why stop at coffee?

Case study: Esther Chepkwony, 56

It’s very stressful to be a woman in this community because women are expected to have all the answers. So much of the family responsibility lies with the women, not the men. We do all the cooking, collecting firewood and caring for the children.

A woman is the intermediary between the husband and everyone else in the family. Any issues always come through the mother first. If anything goes wrong on the farm, she deals with that, too.

Women in Coffee has helped us to get opportunities. I am a mother of nine children. I’m now able to budget and take care of my children’s needs. Every child is educated.

The extra money helps me live a better life. Before sanitary products were a big problem, underwear was not seen by men as a priority or a necessity and it was shameful to ask a husband for a sanitary towel for yourself or your daughters.

The social impact is especially great for women who didn't have enough money to support their daughters. Men lure young girls off by offering them money - they are able to take advantage. Some girls drop out of school and get into early marriages for this reason. A lady with resources is empowered to say yes or no.

Now men can see that women can budget well and they see that we’re wise. Before, meals were always ugali (a type of cornmeal porridge) because the men liked it because it was cheap. Now with our extra money we’re able to buy different food - and our husbands also like this.

We are now able to get loans from financial institutions, whereas this used to only be available to men.

Typically men paid for transport and phone credit. Now ladies have mobile phones and can buy their own credit.

If my husband has a financial need, I’m always here for him. But I only support him when it’s needed and not for leisure.

Lizzie Rivera is the founder of ethical lifestyle website BICBIM (bicbim.co.uk)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments