British Vogue showcases the amazing photography commissioned since its founding 100 years ago

Ex-staffer Adrian Hamilton hails the fashion bible’s leading lights - including Lee Miller, Cecil Beaton and David Bailey

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.“If fashion documents were the only ones in existence,” declared Vogue’s wartime editor, the Fabian Socialist Audrey Withers, “it would still be possible to trace with some accuracy the social and political history of a period.”

She was hardly the guardian of her own pronouncement, signing up to the pulping of all Vogue’s archives to aid the war effort in 1940, a decision that has proved far from helpful to Robin Muir in his task of curating the National Portrait Gallery’s exhibition, Vogue 100: A Century of Style, next month.

But then, as the editor who made Lee Miller into a war reporter – sent to Normandy to photograph the medics at work after D-Day she carried on with the US troops to liberated Paris, the Dachau death camp and finally Hitler’s lair in Berchtesgaden – and published Cecil Beaton’s pictures as an official war artist, Miss Withers made more than her contribution to the war effort.

Not everyone was amused by Beaton’s fashion shots of models displaying their ration-period suits in the ruins of the Blitz, nor of Lee Miller splashing happily in Hitler’s bath in his Munich hideaway, but they have stood the test of time as remarkable images of place and occasion.

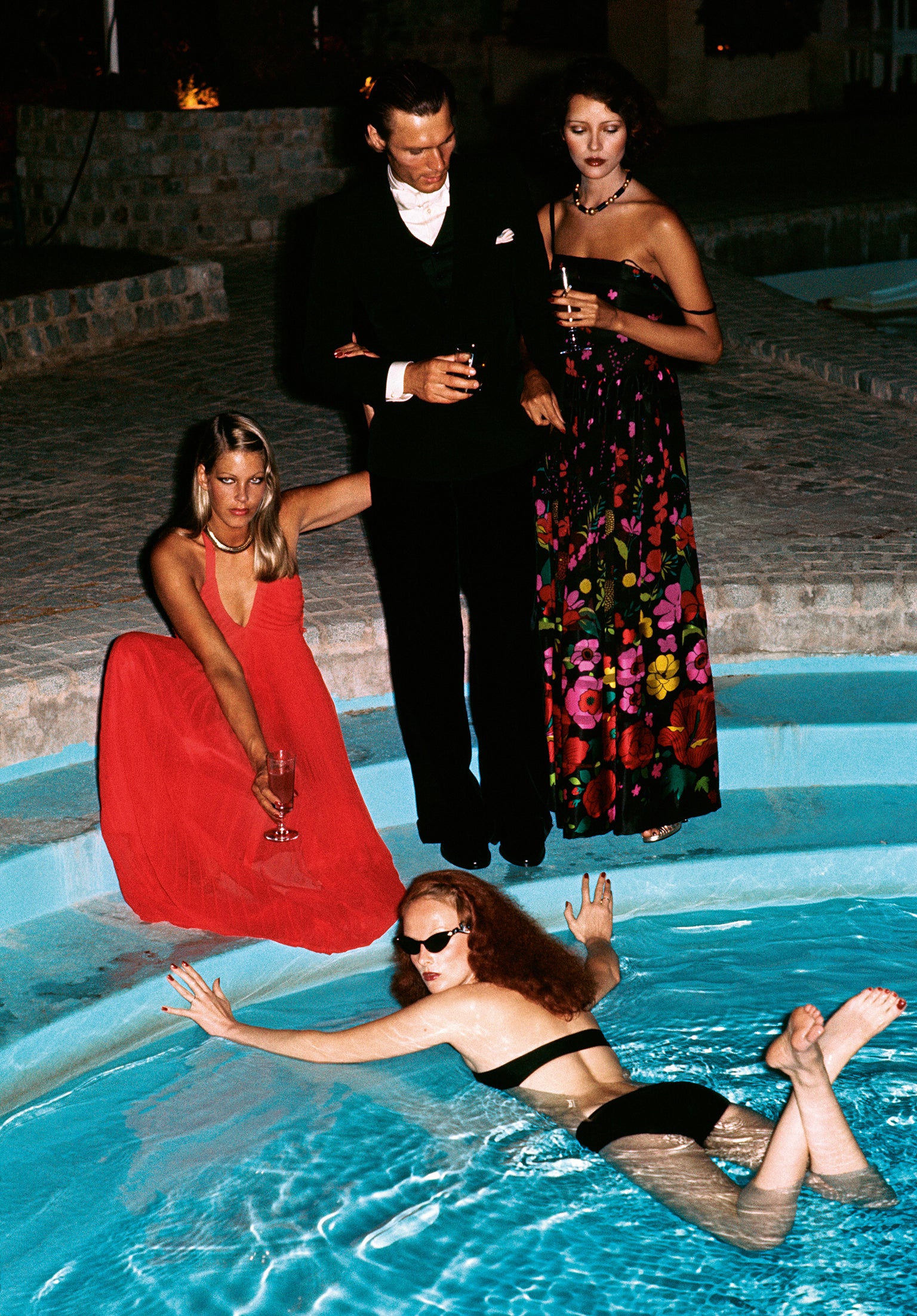

That was the thing about Vogue. You could talk as much as you wanted about “style”, “beauty”, “glamour” and “grace” – as Vogue regularly did in its editorials proclaiming new years, new decades and new fashions – but in the end it was the creation of image that mattered, that one shot in the sheet of contacts that expressed a mood or moment.

For anyone who worked there in the Sixties that mood could be summed up in a single word: “fun”. It wasn’t that we consciously wished to tear up a past that, in the form of those grandees of the fashion shot, Cecil Beaton and Norman Parkinson, were still around and active. We didn’t take much notice of them anymore than they consciously noticed us. Nor did we look to the future. It was the present that mattered.

The result was an extraordinary collegiate expression of energy. Under the beady eye of the editor, Beatrix Miller, Vogue became not just the chronicler of the time but part of it. Bliss was it be alive in the Sixties and to be young was very heaven.

Intrigued by the concept of computers writing poetry, the University of California at Berkeley was promptly commissioned and a poem published (it wasn’t that good as I remember, but it was the concept that counted). I recall tentatively proposing Cartier Bresson as the photographer for a series I’d planned on “Men in Power” and there he was, carrying his two trademark Leica cameras set to different film speeds.

But it was fashion and photography that made Vogue’s name and made the weather. With its three East End photographers – David Bailey, Terence Donovan and Brian Duffy – the fashion pictures breathed sex and spontaneity. They weren’t artless. Little in fashion is. But they were fresh and real.

With Bailey, shoots became not so much a staged event as a happening in which he played master, magician and monster all in one. Donovan was more precise, watching with his eye until he felt the moment, and taking only few shots. Models, always important figures, now became celebrities in their own right, their activities the subject of intense media interest, their opinions and their taste of consequence (I remember being slightly humiliated by being asked to do an interview with one on her love of cats).

Marit Allen, the young fashion editor, worked with designers to produce her own concepts as much as theirs and got Cecil Beaton to photograph Twiggy standing on a mantelpiece. Grace Coddington, a model who became a leading fashion editor, brought traffic to a standstill in Hanover Square and a taxi to veer on to the pavement when she appeared wearing hot pants over bright tights and carrying a bundle tied in a large handkerchief at the end of a long pole slung across her shoulder like a red-headed Dick Whittington. When the Italian cinema director of the moment, Michelangelo Antonioni came to town to make a film, Blow Up, of a photographer based on Bailey, the final seal of cultural approval was put on a world whose players previously thought they were simply enjoying themselves.

The effervescence couldn’t last and it didn’t. Duffy gave up photography altogether, declaring that every picture that could be taken had been. Bailey turned more towards reportage style shooting and more artful portraits, picturing a heavily pregnant and naked Marit Allen as the frontispiece to a book dyspeptically called Goodbye Baby and Amen. Donovan became more and more interested in the Japanese aesthetic and ink painting.

Was it quite as different and new as we thought at the time? It never is, of course. Bailey, Duffy and Donovan – the “Black Trinity” as Norman Parkinson dubbed them – along with Barry Lategan were not the first to take fashion into the streets and models from suburbia. William Klein and other US photographers had already led the way before. Vogue celebrated the Festival of Britain with a “Britannic Number” in 1953 in which it brought over the great American photographer, Irving Penn, to make a series of remarkable portraits of ordinary tradesman and workers. So with the work of Corinne Day in more recent times.

Duffy was wrong. There were still pictures to be taken after the Sixties. Digital photography and technology in the darkroom have allowed contemporary photographers like Nick Knight and Tim Walker under Vogue’s longest serving editor, Alexandra Shulman, to create whole new worlds of fantasy and fairy tale around fashion.

Alongside there has persisted, despite all the social changes, a pursuit of fashion photography as a means to capture beauty and elegance in a single image, best represented today by the work of Mario Testino, classical in its poise and clarity, and going back to the early days of the self-styled Baron Adolph de Meyer and George Hoyningen-Huene through the long reign in Vogue of Cecil Beaton and Norman Parkinson.

Of all the quick found prejudices of youth, the one I have had greatest cause to revise is my estimation of these two figures, who dominated British Vogue throughout the mid century. They were grand and often superior, but looking at their pictures today you can see what great fashion photographers they were.

Beaton, from a middle-class background in love with the idea of monarchy and aristocracy, was always a theatre designer at heart. He summoned up backgrounds and props for his models as for his society sitters to give them a vanishing world in which to present themselves, but all with a sharp eye that saw the artifice and the melancholy of it all. The despair of his friends for his irresponsible lifestyle and in deep trouble for an anti-Semitic jest written for American Vogue, it was the war and his much sought-after appointment as an official artist that sobered him up. In the hangers of the giant bombers, the shipyards of the submarines and the messes of the troops he put his flair for the theatrical backdrop to more monumental use.

Parkinson, or “Parks” as he was known in the office, came in at the beginning of the war and dominated Vogue after it. He was a master of colour and tone, making his models and their clothes seem as beautiful as his society sitters. He brought glamour back to Britain after the privations of war and a nostalgia for the past in pictures such as those taken in India ineffably romantic in feel.

What has made Vogue, in all its national forms, so special is partly the sheer quality of its paper and its print. Founded in the middle of the First World War, Condé Nast from the start invested in high production values and from early on encouraged photography, as later the magazine was a pioneer of colour.

That has given it real class as a magazine but also a certain tension between the artistic and the functional. Its first editor, Dorothy Todd, had to be removed not once but twice after she overspent the budget on commissioning high art articles from her Bloomsbury friends. Since then the magazine has continually oscillated between what Beatrix Miller called “the mood of the moment translated visually” and a more practical bible for women, their interest in clothes and their more personal concerns for diet and well being.

Margaret Thatcher, who learned, at first reluctantly, the importance of clothes as a weapon of politics, firmly told Vogue (she took the same attitude towards political reporting) that “when we look at fashions we would love photographs which show you what clothes are actually like – back and front, and what they look like in movement.” But for the best photographers the picturing of the frock is not a means to an advertising end, but an avenue to more abstract ideas of feminine beauty and the human form.

We were lucky in the Sixties that, just as fashion was democratised, so were we. Class seemed as irrelevant as couture (of course it wasn’t in practice). Since then the fashion world has returned to high fashion and ever more extravagant displays in clothes while photography, which had once influenced advertising, has turned the other way round. The great question is whether fashion magazines, as they move more and more towards the website and the provision of Mrs Thatcher’s call for practical information and illustration, will turn away from the static brilliance of the printed page.

One prays not. Vogue 100: A Century of Style will tell you what you will miss.

‘Vogue 100: A Century of Style’ at the National Portrait Gallery, London, from 11 February until 22 May (npg.org.uk)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments