The It girls: What does it take to be society's most wanted?

Every decade has one – the It girl who captures the spirit of the age and has the look that all the boys love and all the girls want. But what is 'It'? And is Alexa Chung – whose book 'It' is published this week – really the It girl for our times?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Alexa Chung, sometime-model-slash-presenter-slash-creative-director-slash-brand-ambassador, and thrice winner of the British Fashion Council's "Style" award, is adding author to that veritable litany of occupations. It is published this Thursday. "It" is the book's actual title, also serving as pithy summary of the above slash-fest. Because Alexa Chung is "It" – the media's favourite It girl. For now, at least.

Hence the reason It is as hotly awaited as the next Prada collection. Actually, that's a lie: it's as hotly awaited as the new Grazia. Her frenzied fanbase is slightly older than the Directioners sending death threats to GQ journalists, but no less rabid. Alexa is their girl-crush, their "style icon". They sport the bag Mulberry dubbed after her (or a high-street facsimile) and they buy the Alexa-alike wares proffered by stores such as Urban Outfitters. Of course, that store will be stocking It, too.

Chung, of course, is by no means the first to inspire adoration, adulation and copycats in such a manner, but rather the latest in a long line of women who have captured "It" – the public's collective imagination.

"It isn't beauty, so to speak, nor good talk necessarily. It's just 'It'," reasoned Rudyard Kipling's Pyecroft in 1904's "Mrs Bathurst" of this nebulous quality. Racy novelist Elinor Glyn further nailed the concept in her 1927 novel defining "It" as "that strange magnetism which attracts both sexes" – especially appropriate given the female appeal of Alexa et al. Glyn's It was spun out into actress Clara Bow's big silent-screen breakthrough in the same year, bringing the abstract, enigmatic concept of the It girl to international prominence.

Every decade has boasted at least one since – but there were a few precursors, too, women such as the 19th-century actress Sarah Bernhardt, Napoleon's Joséphine, or the great-grandmother of them all, Marie Antoinette. They all had "It", in spades.

The notion of the It girl is tied up with that other horribly overused phrase, the zeitgeist. But it also implies that, when the zeit is ready for another geist, you'll be heading towards the Ex It. There's a transience, a slight tragedy to the It girl. You can't be "It" for ever. Remember that, Ms Chung…

Alexander Fury is the fashion editor of The Independent on Sunday

Marie Antoinette, 1770s

Personality Right royal rebel – teenage brat with a title.

Style Mixed – running the gamut from magnificent to milkmaid.

Why was she It? In 18th-century French court life, the racy world of fashion was preserved for the king's mistress – but when Marie Antoinette ascended to the throne in 1774, she turned that upside-down, positioning herself at the very pinnacle of the fashion game. Women rushed to copy her style, and her mania for novelty in dress gave rise to everything from the powdered and decorated pouf hairdo, to the colour puce.

The centre of a coterie of favoured women – a clique, indeed, ruled by the queen's personal preference rather than the century-old rules of etiquette and status – Antoinette ruled as Queen of Fashion over the whole of Europe. There was even a tacit agreement that her "Minister of Fashion", the dressmaker Rose Bertin, could sell styles sported by the queen to moneyed clients. The catch? Antoinette had to be the first to wear them.

Antoinette certainly had "It" – enemies and supporters alike agreed that she was charming and elegant, her personality often cited as more attractive than her looks. But that, of course, did her no favours politically – by the 1780s, with France on the brink of bankruptcy, many considered her profligacy outrageous. Though when, in an attempt to counter this, Antoinette had herself painted for an official portrait by Vigée Le Brun, dressed in a simple muslin dress, it provoked outrage, with gossips sniping that the queen had been depicted in her underwear. The 18th-century equivalent of a sex tape, it took her a step closer to the guillotine.

Clara Bow, 1920s

Personality Tomboy off-screen, the first sex symbol on – equally wild in both incarnations.

Style The ultimate flapper: cropped hair, high hemlines and lots of lipstick.

Why was she It? As the star of the 1927 film adaptation of Elinor Glyn's novel, Clara Bow was the first girl officially dubbed "It". The runaway success of the movie made Bow's name on a global stage – by 1928, she was the number-one box-office draw. She was also the number-one style icon – with an aureole of curls, short flapper frocks and a dark knot of lipstick, Bow represented the emancipated woman of the Jazz Age. Her visual imprimatur was so strong it inspired not only a slew of look-alikes, but even a cartoon character – Betty Boop.

But Bow's wild-child posturing hid darker roots. In 1923, the same year a 16-year-old Bow had appeared in her second silent movie, her mother was diagnosed with psychosis due to epilepsy, and died. Her father was an alcoholic whom Bow supported well into the 1950s (and her fifties). In 1931, Bow herself suffered a mental breakdown and wound up in a sanatorium – her manager BP Schulberg began referring to her as "Crisis-a-day-Clara". She married and had children, but in 1944, she tried to commit suicide, and was committed again in 1949. The trickier parts of Bow's life were glossed over by the Hollywood star machine.

Bow was one of the first sex symbols and, with women freed from constricting skirts and corsets – indeed, wearing fewer clothes than ever before – Bow's comparatively flagrant sensuality was part of what made her "It".

Edie Sedgwick, 1960s

Personality Flighty, frightened, and unfortunately ready for self-destruction.

Style Sharp lines, short hair, lithe body and long limbs. A 1960s fashion illustration come to life.

Why was she It? Sedgwick was a rake-thin American model and socialite, born into WASP-y, East Coast aristocracy (one of her ancestors, William Ellery, was a signatory of the Declaration of Independence), who drifted to New York in the early 1960s. Racing through the city in a grey Mercedes and racing through her trust fund with equal speed (allegedly some $80,000 in six months), Sedgwick became the downtown answer to the perennially chic Jackie Kennedy.

In early 1965, Sedgwick met Andy Warhol, becoming part of his Factory set. In between modelling for Vogue and Harper's Bazaar, Sedgwick starred in a clutch of art-house films. The first was called Poor Little Rich Girl – a reference, perhaps, to Sedgwick's past – one brother in Bellevue mental hospital, another lost to suicide, a distant and abusive father and her own ongoing battles with anorexia.

While Warhol's films remained underground, Sedgwick did not: her look of stretch-jersey garments, chandelier earrings and sprayed silver hair received widespread attention. Vogue dubbed her a "Youthquaker"; Warhol called her his "Superstar". That relationship began to sour within a year, however, and by 1969 Sedgwick was hospitalised in connection with drug use. By 1971, aged 28, she was dead.

Yet in that short life, Sedgwick encapsulated a moment in time – and she is now immortalised as the embodiment of the 1960s.

Jerry Hall, 1970s

Personality Prowling sultry sexiness. With a knowing wink.

Style Disco decadence: Frederick's of Hollywood mixed with haute couture.

Why was she It? The words "Jerry Hall" conjure up an immediate, indelible image. In fact, they conjure up quite a few. There's Jerry shot by Norman Parkinson, brandishing a telephone against an azure pool on the cover of Vogue. There's Jerry throwing her head back in the original 1977 advert for Yves Saint Laurent's Opium scent, hair a meander of curls so static you can practically smell the Elnett. And there's Jerry in a blue bikini with wings on her ankles crawling across the cover of Siren, the 1975 album of her soon-to-be boyfriend Bryan Ferry's band Roxy Music. The latter is the most explicit and extreme incarnation of Hall – but she's really a siren in all these images, which guide us through the 1970s, a decade defined by the louche, languid sexiness she epitomises.

Hall left Texas aged 16, moving to Paris where she met the illustrator Antonio Lopez, becoming one of the "Girls" that populated his imagery in international magazines. She also modelled for Karl Lagerfeld, and lived with Grace Jones. In 1977 she met Mick Jagger. And the rest is legendary.

You think 1970s, you think Studio 54, flares, and Jerry Hall. Yet while she summarises the decade, she isn't confined to it; Hall is one of the few It girls to have made the transition to It woman – Kate Moss achieved something similar 20 years later, and they're both with us today.

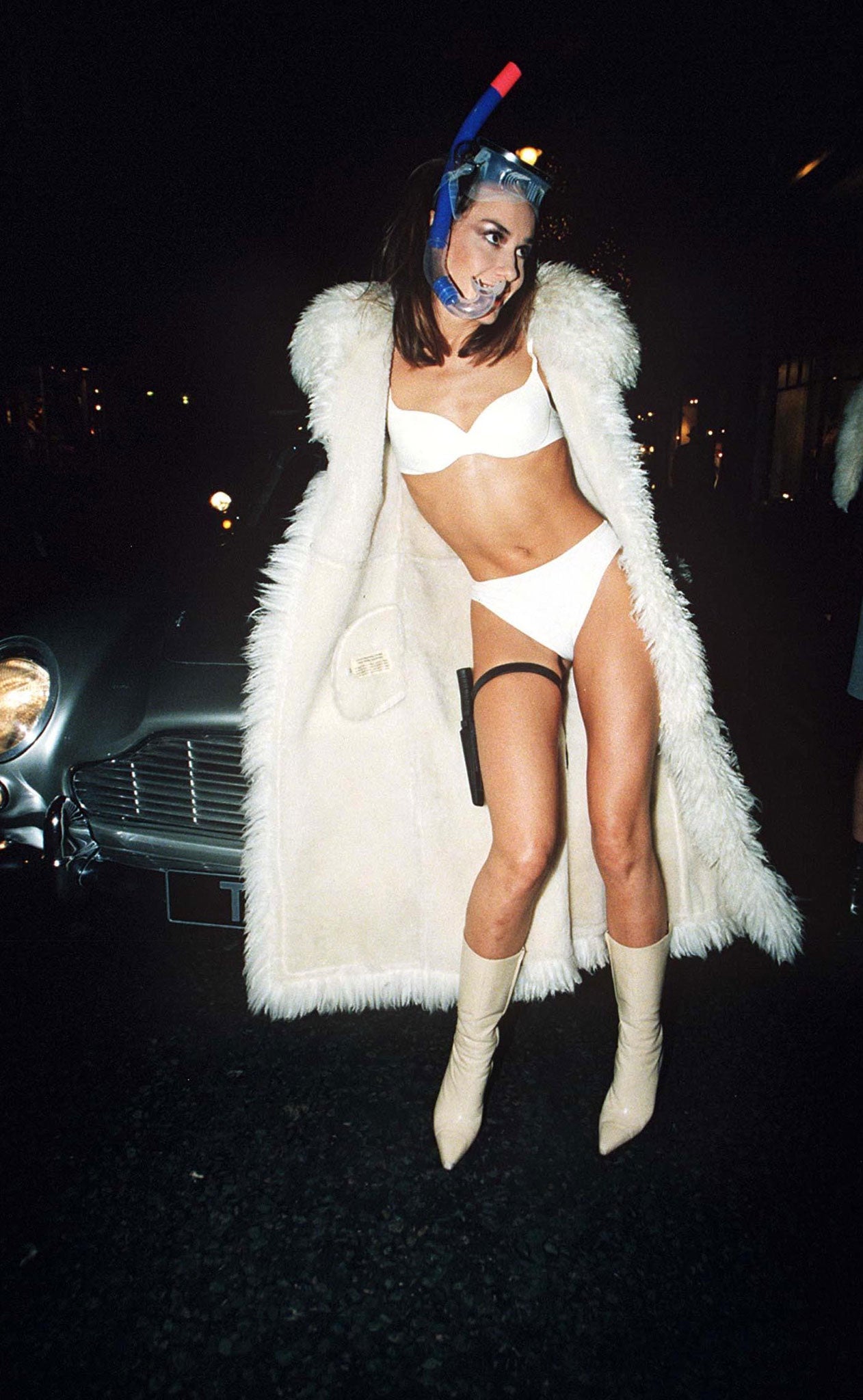

Tara Palmer-Tomkinson, 1990s

Personality Amiable airhead: once banned from Klosters by Prince Charles for allegedly flashing her breasts at Prince William.

Style Questionable at best, diabolical at worst. Always rather expensive.

Why was she It? If Jerry Hall bucks the trend of "It" transience, Tara Palmer-Tomkinson is the apotheosis of an It girl's often-brief shelf-life. TPT, as she was oft abbreviated, was a well-connected, well-to-do upper-class twentysomething who was propelled to kind-of stratospheric fame from roughly 1996 to 1999. After the recession of the early 1990s, seeing someone spending quite so freely and easily was an escapist tabloid tonic. She was also rahly, rahly English – a major "It" factor at a time when British designers were taking over French couture houses and Vanity Fair was devoting covers to "Cool Britannia". TPT graced her own cover – Tatler's October 1996 issue – alongside model and fellow socialite Normandie Keith. The headline? "It Girl".

Other than that, TPT was famous for… well, absolutely nothing, bar inordinate wealth and social connections to the Royal Family. Her sartorial style was that of follower rather than innovator – a penchant for Tom Ford's slick Gucci designs and deluxe hippie chic. However, her very pointlessness was a new development in the canon of "It", and one that assures TPT her place. While Jerry and Edie modelled, Clara acted and Marie Antoinette was Queen of France, Tara Palmer-Tomkinson simply was. What she was was posh, privileged and in the public eye. And that, apparently, was "It".

Alexa Chung, 2010s

Personality TBC.

Style Identikit individuality: ballet flats, smocks, biker jackets.

Why is she It? Where does Alexa Chung sit, then, in the annals of "It"? If Tara Palmer-Tomkinson was notable for doing little to warrant her It-girl status, Chung is a comparative workaholic. She presents television programmes, designs clothing, contributes to British Vogue and indeed pens books. All, it must be said, with varying degrees of success, other than in dress. Alexa's It-girl status is confined, by and large, to the visual. She always looks good.

Her book is the perfect example of "It" – words subjugated to images. Possibly with good reason: I'm unsure if Alexa extolling "Lolita style" should be given a hefty word-count. Luckily, she seems to have focused on the heart-shaped sunglasses used in the poster for the 1962 film rather than any deeper, dodgier interpretation.

The book is devoted to bon mots ("My relationship with my denim hot pants is incredibly special"), selfies and teenage doodles. Chung turns 30 this year, but the content of It could have been culled from the Tumblr of a girl half her age.

And, perhaps, that's why Alexa is "It". She's the It girl for the digital age – the IT It girl. She's photogenic, innocuous, ticking all the boxes of established "It" (rock-star boyfriend, quirky dress-sense, model-turned-something career). She's practically the Wikipedia entry of "It" – and flipping through her book is like scrolling through a Twitter feed: entertaining, but hardly informative. What a testament to our times.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments