Jacqueline de Ribes: Bygone icons, fashion over style, and the importance of taste

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.I normally wince whenever I see the term “style icon” used. Which means I wince a lot these days, as “style icon” is the favoured way to describe everyone from daytime television presenters and vapid society girls to a couple of male models. Few men outside of fashion get the accolade: Vanity Fair's best-dressed list usually features a smattering of European royals as its only masculine components, and the prerequisite current flavours of Hollywood. The phrase is so ubiquitous as to become meaningless.

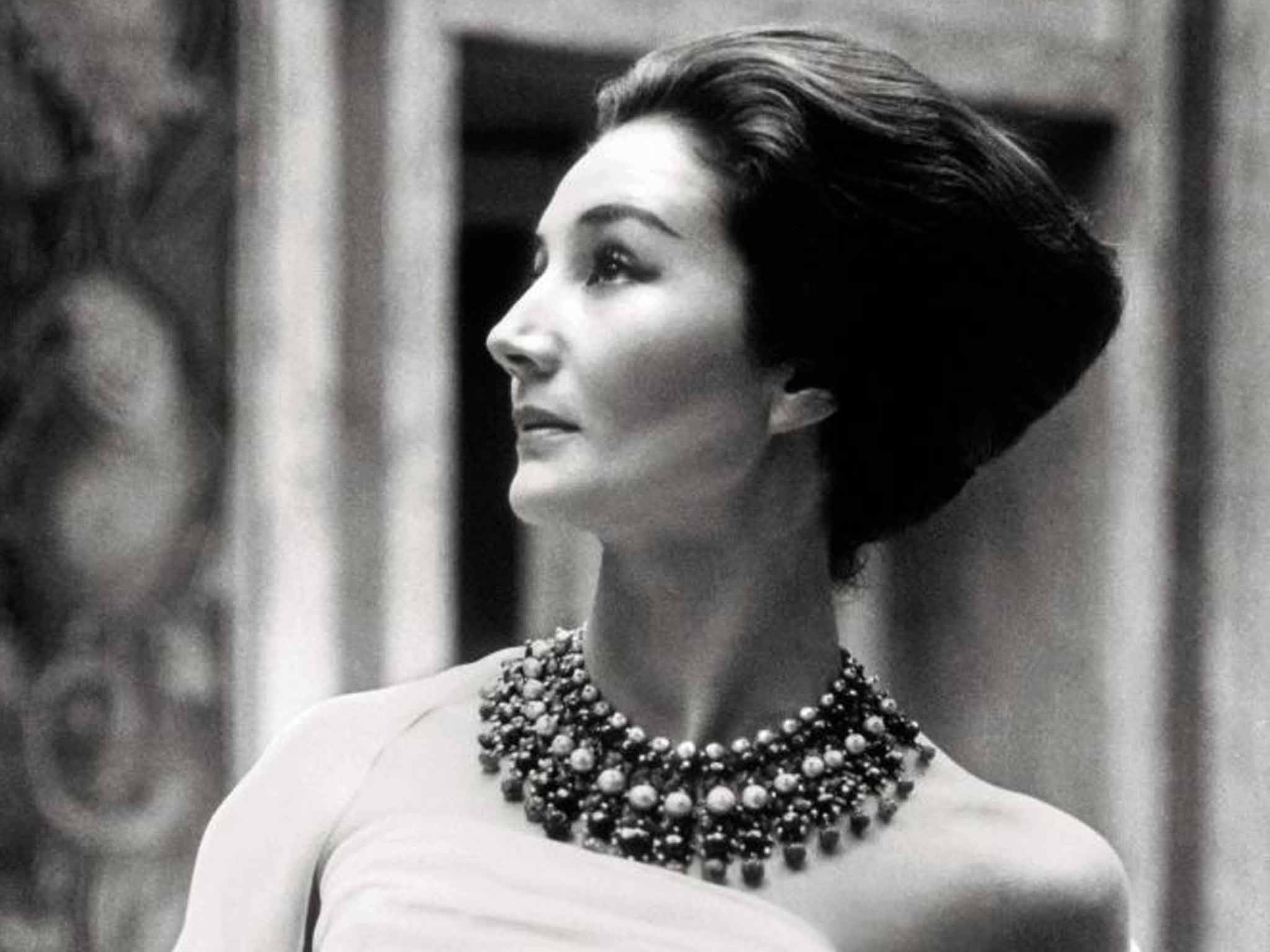

That said, it's the best way to describe Jacqueline, Comtesse de Ribes – a French aristocrat whose expansive, expensive wardrobe is on display in New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art as its winter show. It's called it The Art of Style. That seems as trite a phrase as “style icon”, but it's actually a very canny bit of wordplay to describe a cluster of dresses in a gallery. A selection is designed by Jacqueline herself – she had a fashion business from 1982 to 1995 – but most pieces are by leading designers, from Madame Grès through Valentino and Balmain to Gaultier.

As Jacqueline didn't make the clothes, it isn't a retrospective, as might be given to a designer. And it doesn't chart a specific period of time – her wardrobe is narrow, focused on the life of a member of high society (she designed clothes for that life, too).

But as with exhibiting the work of those collectors of art and fancy stuff that proliferated in the 18th and 19th centuries, there's the matter of taste, and the notion of taste giving a collection of objects a certain authorship. Jacqueline artfully curated her clothes – she bent them to her aesthetic, rather than bowing to fashion's demands. In 1981, she ordered an Yves Saint Laurent dress of orange silk charmeuse; when the house closed in 2002, she ordered the same dress from the retrospective collection in two further shades. It looks as good today as it did then, then meaning both 2002 and 1981.

Do today's “style icons” really have taste? A few, perhaps – though I doubt most people labelled as such have the strength of conviction to order a duo of 21-year-old dresses and still know they'll look good. Today's style is driven by fashion, always changing, with a sell-by date for the clothes and the individuals. Whose clothes will be worthy of a museum show in 30 years? Not many of those “icons”, I'm guessing.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments