All hail the power dressers: Why fashion has always been a place for strong women

In the studio, behind the scenes, in front of the camera, or stalking the catwalk - females rule fashion, says Rebecca Gonsalves

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The annals of fashion are full of legends, the female forebears who paved the way. These are the women who cause a change in the atmosphere when their name – be it one word or two – is uttered, on whose shoulders a collection can not only be built but sold. Some are no longer with us, others are hale and hearty, but there is something important about thesef women, these designers, models and muses who have cast a spell over fashion world.

It may have its detractors, but that fashion is an important industry – with a worth to the UK of £21bn – there can be little doubt. And it is one in which women have excelled, filling top jobs in a visible way that is rarely matched elsewhere. Those women, be they designer, model or editor, are resplendent in their power, cloaking themselves in strength as they would a new-season coat.

This season, a seam of strength and power ran through the shows, and it showed its presence in far more intangible ways than just the clothes. The apex of that mood came courtesy of Mrs Prada, as is so often the case, when the designer presented a group of women – in the words of Bridget Foley of Women's Wear Daily, "each one with a story to tell". What that story may be is open to interpretation, but the need to look beyond the clothes, the hair and make-up is important in itself.

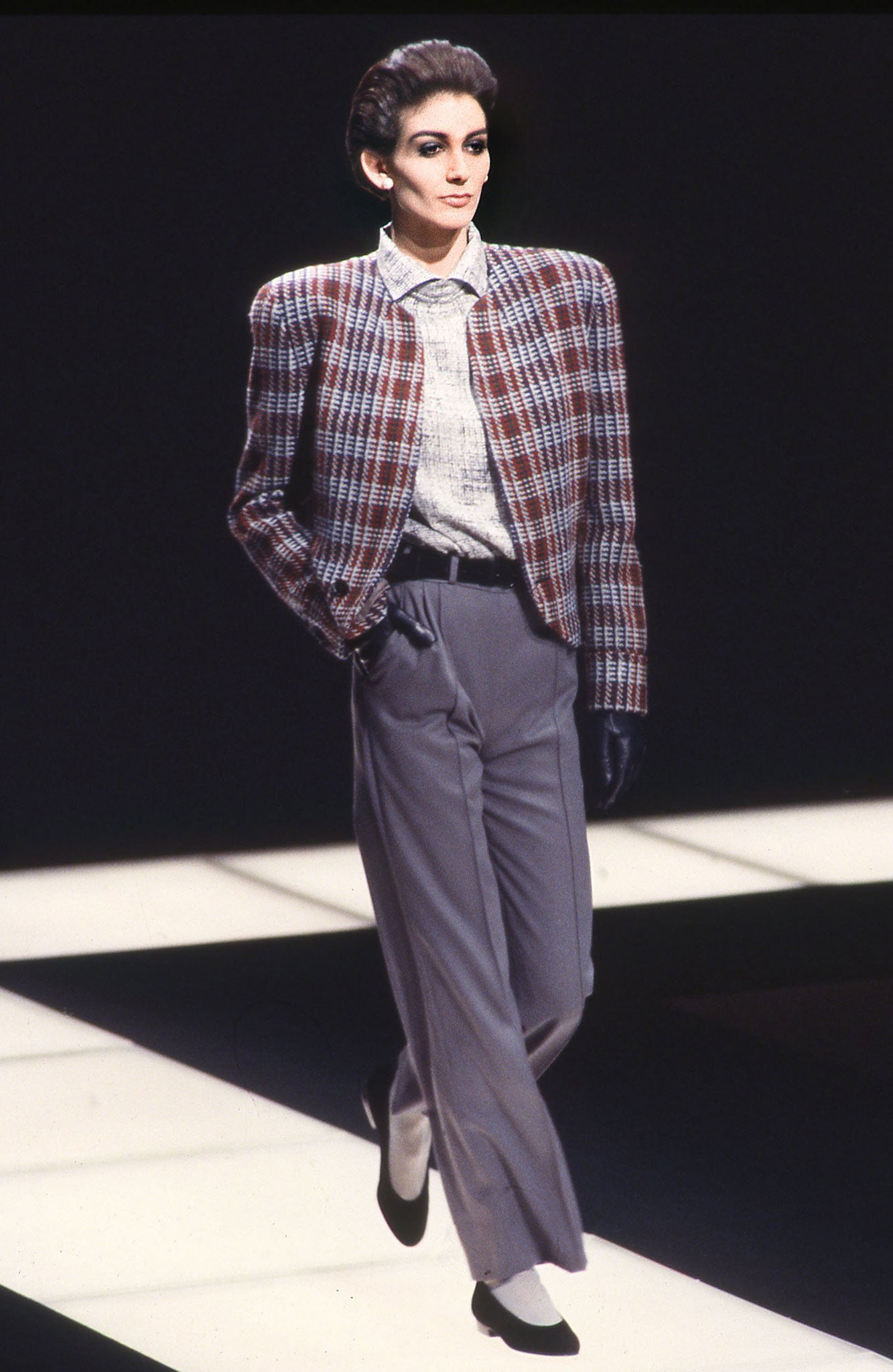

The collections bore out these subtle power plays, too. Modern versions of the suits that so empowered the women who smashed the glass ceiling are cut from traditional tailoring fabrics; shoes are mannish flats, or chunky and clumpy, and all the better for stomping forward in. Whether rounded, squared or folded and tucked into origami folds, shoulders are strong, creating a powerful silhouette that owes more to the traditional male build than the waisted femininity of the past.

Punk returns as a prevalent theme for autumn/winter – with designers providing an exploration of the movement from its new-wave origins to its ultimate demise. The debate over the high-fashion treatment of such a form of expression lumbers on, but should an agreement be reached, it seems unthinkable that studs, zips and nails could provide anything but a message of dissatisfaction and detachment, of strength of mind and body and, above all, of defensive manoeuvres.

On the surface, fashion is about clothes, but the underlying ideologies are just as important as the quality of the cloth. Many designers set themselves the task of creating a wardrobe for real women – admittedly women with bank balances that seem unreal to most.

But those who are responsible for filling their own coffers. Women who would prefer to stand alone and proud rather than as a trophy on the arm of some mogul. This is reflected in a maturity to the collections; while there is space for girlishness and romance, there is an underlying desire to be seen as anything but weak.

Kate Middleton, as she is still called by those who can't bear to reduce a modern, educated woman to the title of duchess, rarely strays from the headlines. And though she has the influence to crash a thousand fashion websites, it is telling that she is yet to truly inspire anything more than a legion of copycats.

Comparisons to the woman who came before her are inevitable, if unfairly premature. Where the people's princess 2.0 has largely pledged allegiance to the British high street, Diana's carefully orchestrated style placed her on a pedestal.

But it wasn't always thus. During her married life, although she may have followed fashion, Diana's wardrobe was chosen to communicate that she was nothing more than a demure and dutiful wife.

It wasn't until after Charles confessed to his adultery, signalling that the marriage was over, that she could be independent enough to relax into the fashion world of which she was so naturally a part.

Gracing the cover of Vogue and attending fashion shows, the mixture of fear and strength that was such an integral part of her persona appealed to fashion's inner circle. Middleton, by contrast, seems like a far safer character – any edges or kinks smoothed out by committee – and where is the fantasy, that lifeblood of designers, in that?

Personality is all-important, as signalled by the return of the supermodel. That power posse of glossy women who charged forward in the Eighties and into the Nineties has returned, as evidenced by Naomi Campbell appearing in catwalk shows again and asking designers about the lack of diversity in their casting, Christy Turlington returning to campaigns for Jason Wu, Prada and Calvin Klein, and Karen Elson showing up on catwalks and in Marks & Spencer's latest adverts alongside a veritable girl-gang of strong women.

While among the current generation of young models there is a cult of personality to rival Campbell et al, thanks to sites such as Instagram and Twitter, which allow would-be mannequins to express themselves to legions of fans without having to play into the hands of brands or the paparazzi printing presses.

That power of personality starts in the studio, too, and not just those of the celebrity-turned-designers whose task is one of continuous reinvention. In most fashion circles, Phoebe Philo's name is spoken in hushed, reverential tones.

Understandable, as she is a woman who has set the agenda in fashion, with her wearable, covetable take on luxury womenswear for Céline. But more than that, she has done so on her own terms.

Philo is a true power player, one who refused to move to Paris when expected, who reduced the brand's catwalk show – a major event on the Paris schedule – to an intimate presentation due to maternity leave.

Now that she has been reduced to the sort of easily digestible soundbites that litter the internet, it's easy to forget that Coco Chanel was a real revolutionary in her time. She created not only the persona and past that she wanted for herself, but she also liberated women, transforming the female silhouette and emancipating them from the corsets and stays that society had used to bind women for centuries.

Every decade has its mode of dress – the preeminent vision for the career woman or girl about town and how best to arm her for the battles of the day. For the designers, she exists in the space between reality and complete fantasy, providing a manifesto of sorts. The Sixties saw the introduction of the miniskirt, heralding the end of society as it was known as revolution swept the country, led by a disenfranchised youth.

In 1974, women were given the wrap dress, designed by Diane von Furstenberg, a former princess by marriage who remained fiercely independent. In the Eighties, Giorgio Armani's suits were armour for those working girls off to do battle in the boardrooms – giving the wearer the powerful swagger of a man without erasing femininity entirely.

Each design is synonymous with the power struggle of its time, but what will come to define this decade that doesn't even have an agreed name? It's perhaps too early to tell, but as the stripped-back, post-recessionary aesthetic perseveres, instead of dictating a new ideal to women every six months via flip-flopping trends, designers are now pursuing a continuation of a vision each season, slowly colouring in the lives of the woman they have sketched out.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments