What Donald Trump's 'man cave' says about him according to a sociologist

Men's boltholes are far from innocuous, according to a sociologist investigating why they exist

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

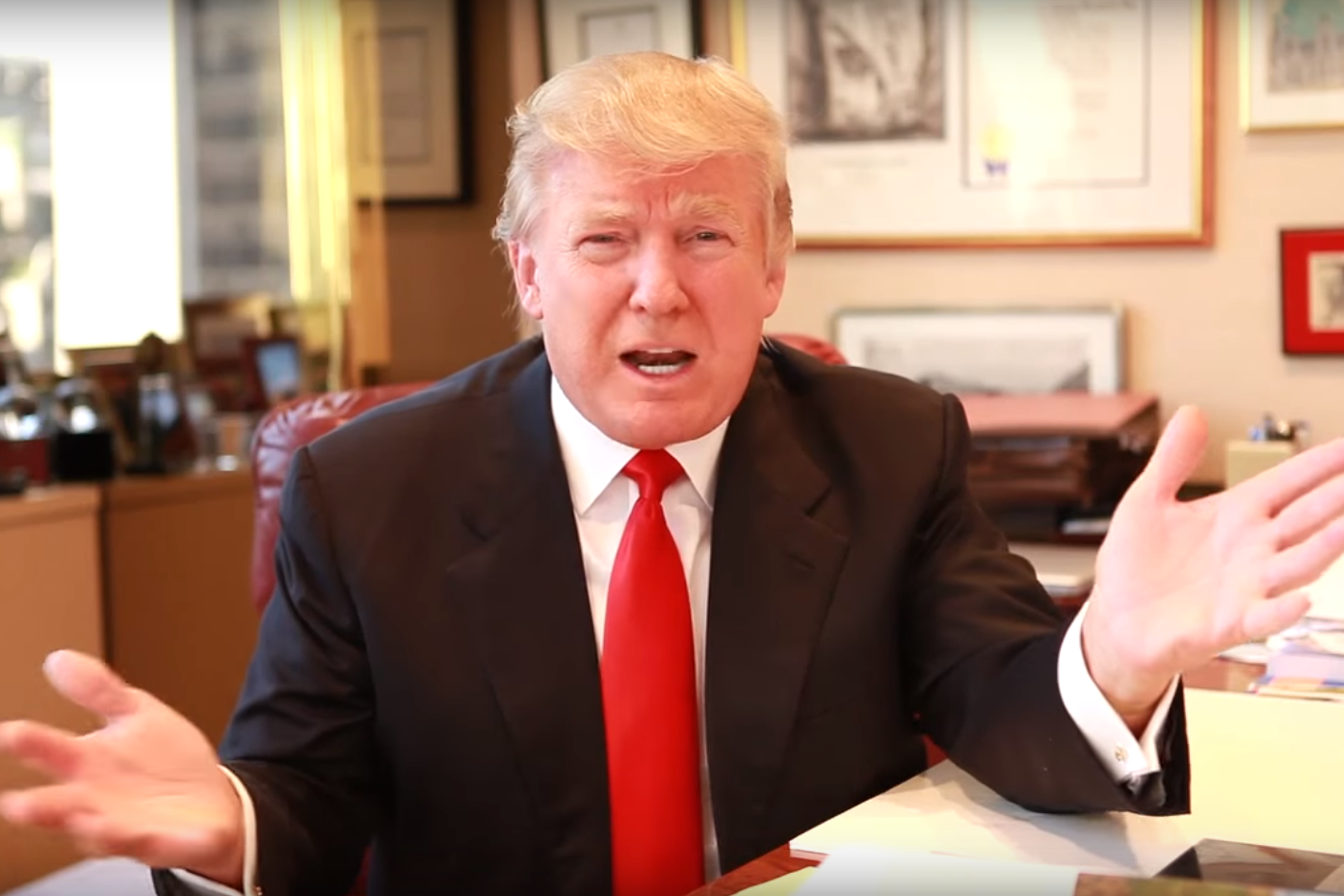

Your support makes all the difference.The awards, magazine covers and pieces of furniture that make up Donald Trump's office offer an insight into how the President-elect might be using his personal space to assert his authority over other people, according to an expert in so-called “man caves”.

Images of Mr Trump's office in Trump Towers, New York, show that the wall beside his large desk is decorated with The Nathan Hale patriot Award musket; an America's Cup yachting foundation award; the Tree of Life humanitarian award from the Jewish National Fund in 1983; and his Sholom humanitarian award from the Jewish community. Elsewhere in the room are magazine covers which Mr Trump has appeared on - including Fortune, GQ, and a 1990 copy of Playboy. On his desk stacked with papers are copies of Unprecedented, the CNN book on his shock US election victory in 2016, as well as an image of his father.

Tristan Bridges, a sociologist at the The College at Brockport, State University of New York, has visited numerous man caves, and spoken to the men behind them to try to pinpoint what they say about their owners, as well as gender politics and relationships in the home.

“Donald Trump's office is dominated by him in every respect. It appears as if it is designed to intimidate,” he tells The Independent after studying images of Mr Trump's office.

“His room allows him to say 'As a man with so many talents, I could have taken any path. It is unfortunate that I couldn’t lead multiple lives',” says Dr Bridges.

Dr Bridges adds that the businessman appears to have arranged his space in order to confront those who he invites in with evidence that he is a “renaissance man”.

“From the space he looks well-read,” he says.

Commenting on the piles of papers on Mr Trump's desk, Dr Bridges adds: “it is interesting to want your space to look that messy. I think Donald Trump likes to be known as someone who can juggle an endless number of balls, so he has wants a space that looks like that. And someone meeting him has very little space to use for themselves.”

As for huge desk and large office chair, these set Mr Trump above those who come to meet him but also look like furniture from a high-end men's club, adds Dr Bridges. This is in line with Mr Trump's characteristic conspicuous shows of wealth.

The copy of Playboy, argues Dr Bridges, plays with the idea of a man cave as an evolved bachelor pad, usually seen in a domestic space.

“Man caves are more of a space about fantasy than anything in particular. They are a way for men to imagine what their lives could have been.”

Speaking generally, Dr Bridges argues that “man caves” may seem like a tongue-in-cheek refuge from the drudgeries of domestic life, but they are actually a very serious business.

The phrase in itself is loaded: suggestive of a “them vs us” set up, and an apparent biological need for men to return to knuckle-dragging ways that women can’t understand.

However, while the phrase might conjure hyper-masculine images of stacked beer kegs, table football, and thumbed posters of bikini models, man caves are in fact more varied and complex than one might expect. This, argues Bridges, is not only reflective of how ideas of masculinity have changed over time but how the priorities of men develop with age. Overall, he says his findings confirm that gender is just one big life-long performance.

By studying man caves, Bridges hopes to understand how masculinity has shifted over time, and see if they contain clues of how we will live in the future as gender binaries become archaic.

As part of his study, Brock poked around the man caves of twelve couples that identify as heterosexual, gay, and lesbian.

“Man caves are all about power and control,” he argues. “And they're often undertaken with an air of humour, which makes that power and control appear to be less serious than it is. But make no mistake, man caves are serious business.”

“It’s an enormous industry,” says Bridges. This is backed up by the reams of content online advising on how to customise man caves, from articles to Pinterest boards.

As gender equality is slowly won, man caves take on new meaning, he suggests. The kitchen, traditionally seen as a woman’s domain, is the most renovated room in the American home, he says, a trend comparable to other Western countries.

“That’s because family life has transformed since a great deal of homes in the US were built. These homes were built to suit gender arrangements between couples that are less true today. So, we feel ‘cramped’ and ‘stifled’ in those same spaces that families a generation or two ago would have been ‘free’.”

Lots of man caves I've seen have different rules, like allowing cussing, farting, misogyny, and having no women

What unites many of the man caves that Bridges has investigated are ideas of indulging in nostalgia and creating a retreat away from polite society.

“Lots of man caves I've seen have different rules, like allowing cussing, farting, misogyny, and having no women,” he says.

Indulging in traditionally masculine pursuits and forging intimate bonds with male friends are also seen as important, particularly for younger men who furnish their rooms as boltholes for watching sports and drinking.

Older men, however, are more likely to have what Bridges describes as “tinkering dens” with only one chair, dedicated to hobbies such as metalcraft, toy train building, or completing puzzles.

“They're places these men feel they can ‘get away’ and find some privacy.”

“Gay, lesbian, and straight couples' man caves have been different as well,” he adds. “Women's and gay men's ‘man caves’ are rooms that are undertaken more humorously than are heterosexual man cave.” Interestingly, women’s caves are taken more seriously and are more complete than men’s.

Nevertheless, Bridges sees man caves as problematic not only because they are inherently sexist, says Bridges, but are based in ideas that are historically inaccurate.

"Early humans were actually much more cooperative than we often think. Many early societies were intensely gender egalitarian, and historical evidence does not support the lumbering, sexually aggressive, club wielding caveman we like to depict in popular culture.

"We call them 'man caves' because it creates the sense that they are associated in some way with men's biology, and that men need these spaces on some kind of biological level. But men are not inherently misogynistic. They're not inherently sexually rapacious. But the space the man caves occupy in our collective imagination allows us to believe those myths about men, a set of beliefs that hurts both women and men."

Such theories are hardly ground-breaking. But what has shocked Bridges the most, though, is that many of these rooms are barely used at all.

“The man caves I’ve seen so far are unfinished and most of them are rarely if ever used for the community events they seem to be designed to host. So, why are men spending so much time and money creating and cleaning a space that isn't used for what they claim they want from it?” That is a question Bridges is yet to answer.

In the future, as gender norms continue to fall away, the man cave will sure simply become a laughable concept? Bridges isn’t certain.

“If they still exist what people thought of as important to put in those spaces to signify them as ‘masculine’ would change dramatically. And that is fascinating to me.”

What he is clear of is that however playful a man cave might seem, we could do with seeing the back of the ideas and gender stereotypes that they are based around.

“The space the man caves occupy in our collective imagination allows us to believe those myths about men, a set of beliefs that hurts both women and men.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments