Bauhaus changed the world but did it make it better?

Industry offered Bauhaus designers a chance to conceive anew what it meant to be human – liberated from the humiliating inheritance of the past and, as Gropius called it, 'romantic prettification and cuteness'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In 1919, there was a lot of talk in Germany about building a better world. The First World War had ended in crushing defeat and political chaos, and so much was literally in ruins. The need for new homes alone was acute, and it wasn't only a matter of what the buildings should look like, but also how quickly and cheaply they could be built. The talk extended beyond practicalities. The urge to fix things, to put the pieces back together, affected everything. The question wasn't just: "What sort of government do we want?" It was: "What does it mean to be human?" and "How should we therefore live together?"

The Bauhaus art school rose out of all this. Its aim was to revolutionise everyday life. You are living with its legacy. And so, for better or for worse, are the residents of Brasilia, Beijing, Tehran and Tel Aviv. Bauhaus, 100 years old this year, is the subject of celebrations and reappraisals around the world. The anniversary is already igniting passionate debates, because no other institution is more closely identified with modernist architecture and design.

If you like airy, light-filled buildings, functional furniture, elegant, affordable design, sans-serif typography and clean-lined graphic design, you care about the Bauhaus. Equally, if you hate boxy, flat-roofed buildings, relentless standardisation, the death of curves, ornament, the ironing out of cultural differences and overly rational planning, you care about the Bauhaus.

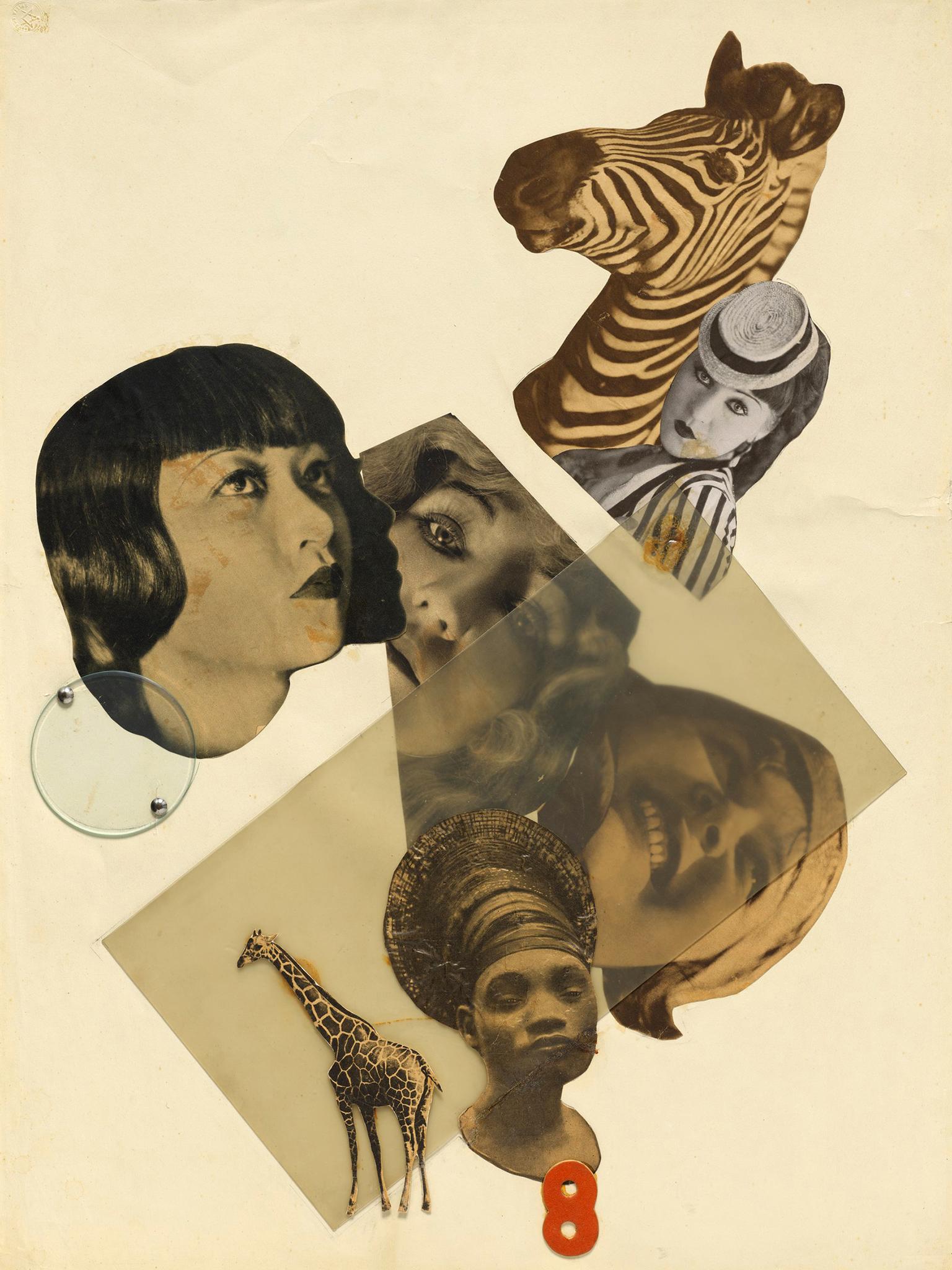

Harvard Art Museum owns the finest collection of Bauhaus material outside Germany. Its new show, The Bauhaus and Harvard, illustrates the full range of Bauhaus activities during the school's 14 years of existence in three locations in Germany. After the school was dissolved under Nazi pressure in 1933, several of its key figures emigrated to the United States, so the show also traces the Bauhaus's impact on education and design there – at Black Mountain College in North Carolina, the New Bauhaus in Chicago, Brooklyn College in New York, Newcomb College in New Orleans and Harvard.

There are almost 200 objects in the exhibit: from art class exercises on paper and architectural studies to furniture, textiles, photographs and paintings. There are impressive large-scale works, but the overall emphasis is on small-scale works and ephemera, which might leave you guessing at the scope of the Bauhaus's impact. It was, in a word, vast.

The Bauhaus opened in 1919 in Weimar, the home of Goethe and Schiller, not 20 minutes' drive from where, 18 years later, Buchenwald, the largest concentration camp within Germany's borders, would be established. If the crisis from which the Bauhaus emerged was caused by things falling apart – individuals fractured from communities, workers cut off from profits, neighboring nations at war – the solution, it seemed, was to reunify.

"Today the arts exist in isolation, from which they can be rescued only through the conscious, cooperative effort of all craftsmen," wrote the architect Walter Gropius, Bauhaus's first director. He established the school by merging a fine art academy with an applied arts and crafts school.

In this new, unified take on art and design, the Bauhaus echoed the 19th-century Arts and Crafts movement, which cherished handcrafted things as an antidote to factory-made objects and the wider effects of industrialisation. Bauhaus under Gropius initially followed suit. Early influential Bauhaus teachers, such as Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky and Johannes Itten, cultivated the intuitive, spiritual side of art and learning.

But by 1923, the emphasis had changed. Gropius announced a determined focus on designing for industry. Factories – the "dark Satanic mills" of the Industrial Revolution – were no longer the enemy. Industry was to be the solution. And industry also would determine the aesthetic. The boxy buildings Gropius designed, with large windows and open plans, were remarkable for their resemblance to factories. "Enough with thinking, dreaming and hiding away from the world," they seemed to announce. "It is time to live with purpose!"

The Bauhaus's influence on pedagogy was as profound as its impact on actual design. Every student who studied there had to participate in a preliminary course. In the beginning, it was taught by Itten, whose methods were holistic, combining composition and color theory with calisthenics, and later by Josef Albers and Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, who both had an outsize impact on the teaching of art and design in the US.

Their approach exemplified the Bauhaus's search for a new unity – not just of art and craft, but also individual and society. The keynote was simplicity. If you stayed focused on fundamentals, went the thinking, expertise would be less likely to splinter off into areas of specialisation.

The Harvard show, curated by Laura Muir, begins with examples of preliminary course exercises. These demonstrate how, in a spirit of experiment, students were encouraged to discover the properties of shape, color and materials – to learn, for instance, how the visual impact of colored pieces of paper could change according to such simple things as the color of the background, the pattern of overlap or shifts in tone, and how illusions of spatial recession or transparency might be similarly affected.

The exhibition continues with a display of the Bauhaus's radical designs for houses and furniture, then sections devoted to the school's weaving and photography classes, as well as its spread beyond Germany, first to Paris and then to the US.

We see works by modernist figures whose reputations transcend their association with the Bauhaus, from the painters Kandinsky and Klee to the architects and designers Marcel Breuer, Gropius and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. There also are remarkable creations by such dynamic figures as Albers, Herbert Bayer, Lyonel Feininger and Moholy-Nagy.

Bauhaus was dominated by men, but Muir has made an effort to foreground the influential textile artists Anni Albers and Gunta Stölzl, as well as works by lesser-known women, among them the weaver Otti Berger and the photographer Lucia Moholy.

"The Bauhaus and Harvard" culminates in a display of murals and wall sculptures commissioned for the Gropius-designed Harvard Graduate Centre, erected in 1950. The most impressive is "Verdure", a stunning, 20-foot-wide study in dynamic rolling forms and shades of luminous green by Bayer.

Gropius and his colleagues wanted artists to be useful and to help rebuild society along rational lines. Industry offered Bauhaus designers a chance to conceive anew what it meant to be human - liberated from the humiliating inheritance of the past, from absurd, old-fashioned ornaments and, as Gropius called it, "romantic prettification and cuteness."

But that meant Bauhaus designers were impatient with cultural variations and with the idiosyncrasies of individual lives. "The individual declines increasingly in significance," Mies wrote, "his fate no longer interests us."

Even as we celebrate all that the Bauhaus contributed, these words should sound an alarm for anyone conscious of the course of the 20th century and, for that matter, anyone worried about the conveniences today made possible by algorithms and artificial intelligence. (As Lionel Trilling once warned: "Some paradox of our natures leads us, when once we have made our fellow men the objects of our enlightened interest, to go on to make them the objects of our pity, then of our wisdom, ultimately of our coercion.")

Bauhaus modernism is discussed these days as if it were just another style, like Art Deco. But it also was an ideology of conviction. Its roots were in the European Enlightenment, but its founders were convinced it could transcend history. Everything was to be about truth, transparency and the outward manifestation of reason. Outdated symbols were to be jettisoned. The repressed was to be made visible.

The healthy ideal of unification, however, quickly became a ruthless drive toward uniformity. The Bauhaus's progeny produced millions of buildings of unparalleled ugliness, blighting urban environments worldwide. Wherever local differences were encountered, they were suppressed. Behind the Bauhaus's admirable idealism, you sense a kind of disgust with difference, and with humanity as it is.

The Bauhaus itself disgusted not only Hitler's Nazis, who associated it with communists and Jews and forced its closure shortly after they came to power, but also with Stalin's Soviets, who rejected modernist aesthetics as abstract and elitist. In the long run, persecution by both the totalitarian right and the left helped make Bauhaus-style modernism the preferred aesthetic of the democratic left, magnifying its influence – and perhaps prolonging people's blindness to its inherent flaws.

© Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments