Coco Chanel: Nazi collaborator AND brave resistance fighter in wartime Paris?

At a sensational new show at the V&A exhibition, Katie Rosseinsky investigates the 20th century’s greatest innovator, who changed how women dress

Gabrielle “Coco” Chanel was a revolutionary, blazing through the stuffy world of early 20th-century fashion to free women from their corsets and change their wardrobes forever. But her fascinating, complicated story goes far beyond her influential style, encompassing alleged Nazism, thwarted secret operations and ties to some of the major figures in the Second World War. On one hand, it’s surprising that Chanel’s intrigue-laden war has never made it onto the big screen; on the other, it’s not so shocking – why would one of the world’s biggest fashion houses want to play up their founder’s links to the Nazis?

The V&A’s new exhibition, Gabrielle Chanel: Fashion Manifesto, cleverly captures the contradictions of the woman who was born to a travelling street vendor and a laundrywoman in small-town France in 1883, but rose to become one of fashion’s great innovators. The show intrigues from the start. As you enter, you wind your way down a partially mirrored staircase; towards the end, you will see a staggering array of evening gowns, displayed along a similar flight of stairs, also panelled with mirrors. Both are a nod to the famous escalier at Chanel’s premises on Rue Cambon in Paris, which took the legendary designer up to her private apartment. The effect is disorientating: you’re confronted with various fragmented versions of yourself, and of the dresses on display, as if you’re in a very fashionable fairground fun house.

Your reflection appears at a slightly different angle in each panel. It’s an appropriate trick for a show exploring a woman who remains extremely hard to pin down more than 50 years after her death. There are many possible versions of Chanel’s life. Some of them she fabricated herself, attempting to rewrite her origin story; some play up various angles, some conveniently elide her prejudices and her links with hardline nationalists like her lover Paul Iribe, the founder of a far-right journal; some turn her into a jumble of witticisms and pithy sayings in a coffee table book.

Perhaps the most unsettling of Chanel’s contradictions has always been the fact that the great liberator of women’s fashion was rumoured to be an antisemite and Nazi collaborator – but the V&A exhibition only makes that picture yet more complicated, thanks to its revelation that Chanel was also part of the French Resistance during the Second World War. It’s not quite an attempt to rehabilitate her fraught past, but it certainly shows that there are yet more layers to this complicated woman, who loved to dress her models in crisp black and white but seemed to live in the murkier shades in between.

The facts of Chanel’s youth are a little blurry, thanks to her fondness for revisionism (in her biography Coco Chanel: The Legend and the Life, Justine Picardie tells how she altered the birth date on her passport in pen, to appear younger). After the death of her mother, her father abandoned the family, and she and her sisters were sent off to an orphanage attached to a convent in Aubazine, in France’s Nouvelle-Aquitaine region. Recalling her early life, Chanel would paint an alternative version of her history, where she was taken in by strict aunts.

At the orphanage, she learned to sew, and it’s not hard to see the austere black and white attire of the Aubazine nuns reflected in her later designs; some biographers even see echoes of rosary beads in her long pearl necklaces. When she turned 18, she worked as a seamstress and sang in a cabaret (her go-to songs “Ko Ko Ri Ko” and “Qui qu’a vu Coco” are thought to have inspired her nickname, although Chanel would claim that it came from her father), later becoming the mistress of cavalry officer and textile heir Étienne Balsan. Through Balsan, she met Arthur “Boy” Capel, the wealthy British merchant who would become the love of her life. It was around this time that Chanel started up her first fashion venture, buying up straw hats from Galeries Lafayette in Paris and adding subtle trimmings. Balsan and Capel were, in a haphazard way, her first financial backers: the former provided premises, allowing her to set up shop in his city apartment; the latter covered day-to-day costs. It soon grew too popular to operate out of Balsan’s flat, and in 1910, with more of Capel’s money, she opened a shop on Rue Cambon in the 1st arrondissement.

Some of Chanel’s biographers focus on the influence – financial and creative – of her various lovers on her signature style. They draw a line between her fondness for traditionally masculine tailoring and the suits worn by Capel and, later, by Hugh “Bendor” Grosvenor, the 2nd Duke of Westminster, whose decade-long affair with the designer started in the early Twenties (the Duke was one of Europe’s richest men; Chanel’s iconic tweed bouclé jackets, some argue, were inspired by the traditional tweed sports coats he would wear on their jaunts to the Scottish Highlands). And her relationship with the Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich, one of the assassins who killed Rasputin, is cited as the influence for her Russian period, which saw her adopt traditional Russian embroidery, square-necked roubachka blouses and fur-lined coats.

Chanel certainly borrowed heavily from all of her relationships, romantic or otherwise. Her friendships and collaborations with the likes of artist Pablo Picasso, writer Jean Cocteau and Ballets Russes founder Sergei Diaghilev provided inspiration, too: in the BBC’s new Arena documentary Coco Chanel Unbuttoned, biographer Rhonda Garelick describes the designer as almost vampiric in her ability to “suck out what was most interesting and delicious and life-filled in other people, aesthetically, intellectually, artistically” and then use it in her work. But she was fiercely independent too. When her business was in its early stages, she was horrified to learn that she had not yet managed to pay off her debts, and that Capel was still her guarantor. “I threw my handbag straight at [Capel’s] face and I fled,” she later recalled to biographer Paul Morand. Arriving at her workshop the next morning, she told her head seamstress: “I am not here to have fun or to spend money like water. I am here to make a fortune.” One year on from this episode, she no longer needed Capel’s support.

Overplaying the influence of the men who drifted in and out of her life risks understating her own selling power, too. Chanel was her own best advert. At first, customers flocked to the Rue Cambon shop out of curiosity, to see this young woman who dressed like a boy, and whose unfussy straw hats couldn’t be further from the heavily embellished headwear favoured by most society ladies. When she started making clothes in the seaside town of Deauville, just before the outbreak of the First World War, she replicated the simple, almost utilitarian shapes that she liked to wear herself.

Her innovation was to use practical jersey cloth, a fabric then associated with men’s underwear, not fashionable womenswear. It was probably one of the only materials she could get hold of easily and at scale during wartime. But with its loose, easy fit, it also suited women’s new, more dynamic lives. As they slipped into the jobs left empty by the men who had gone away to fight, fussy gowns and restrictive corsets (which had already been ditched by more established designer Paul Poiret, a rival of Chanel’s) felt like an anachronism. The previously fashionable S-bend shape – which pushed the hips back, the chest forward and the waist in – was out, and a more natural silhouette was in. “I liberated the body, I discarded the waist, I created a new shape,” she would later say, in typically grandiose style. She was right, to a point. Chanel’s designs brought a new level of freedom to women’s wardrobes – but this more “liberated” shape was best shown off on a skinny frame like hers, ushering in a new emphasis on thinness.

Tanned, slim and glamorous, Chanel had figured out that the best way to shift clothes was to sell the aspirational lifestyle that goes with them. Her next commercial masterstroke was to bottle and sell her essence. In 1920, she worked with master perfumer Ernest Beaux to create a fragrance that felt as modern as her fashion designs, a departure from the more traditional floral scents popular at the time. Beaux and Chanel each played up their own involvement in the making of their first perfume, but the myth with most staying power sees the designer challenging the perfumer to come up with a scent to make its wearer “smell like a woman, and not like a rose”; Beaux then presented her with a series of numbered prototypes, and Chanel chose the fifth one.

Five was already her lucky number, and Chanel No5 was born. It was one of the first perfumes to fuse natural scents like ylang ylang, sandalwood, rose and jasmine with aldehydes, organic chemical compounds that can change a fragrance’s profile. Chanel surreptitiously launched her perfume onto French high society with a sort of immersive marketing stunt, spritzing it when fashionable women passed her table while dining in Cannes with Beaux. Later, she would spray it in her boutiques to pique the interest of her loyal customers before the scent was widely available, then gave her best clients bottles as a Christmas gift in 1921; word got around, as she’d no doubt intended, and the following year No5 went on sale in her shops. Demand outstripped supply. In order to step things up, she made a deal with Pierre and Paul Wertheimer, the brothers who owned the cosmetics company Bourjois: they would buy the rights to Chanel’s name and launch Les Parfums Chanel.

No5 was far from Chanel’s only innovation of the Twenties. As modernism roared through Paris, she popularised trousers (much better for getting in and out of gondolas, she decided after a trip to Venice) and pioneered pyjamas, with their scandalous suggestion of the bedroom, as daywear. Perhaps her most revolutionary launch, though, was the little black dress. At the start of the century, black was considered too dour and funereal to be truly stylish. But after a period of grief following the untimely death of Capel in a car crash in 1919, Chanel decided to radically reclaim the colour of mourning. When she unveiled her simple sheath dress in black crepe de Chine in 1926, American Vogue hailed it as a game-changer. They called it “the Chanel ‘Ford’ – the frock that all the world will wear”. She had changed fashion forever. One of the many, possibly apocryphal, stories about the designer features a black-clad Chanel passing her rival Poiret in the street. “Well Mademoiselle, who are you in mourning for?” Poiret asked her. “For you, dear Monsieur!” was her response.

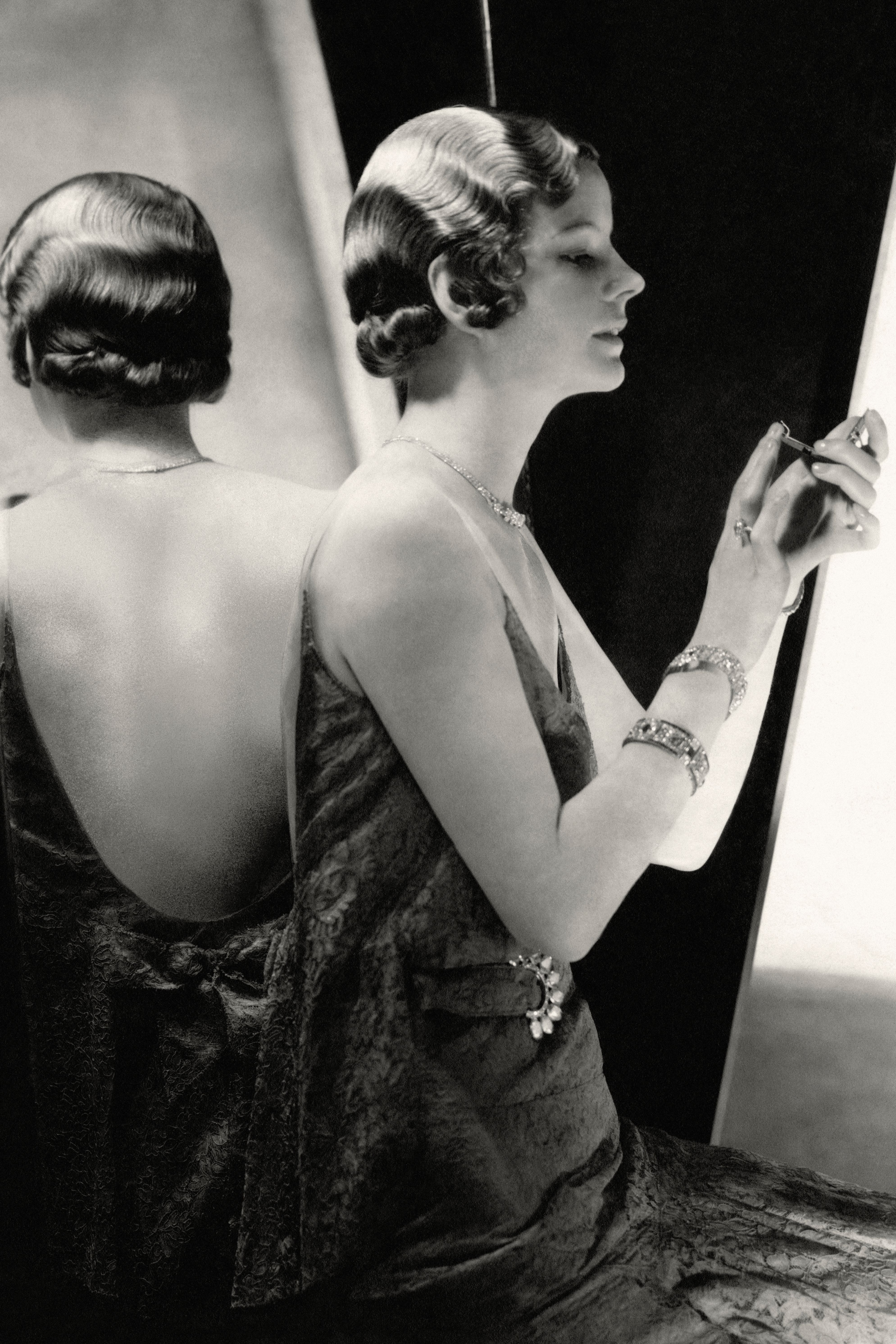

By the 1930s, Chanel had made good on that earlier vow to “make a fortune”. TheNew Yorker reported at the time that she was worth “some three millions of pounds”, which, they helpfully clarified “in France, and for a woman, is enormous”. Not bad for a fashion designer who, the writer added, didn’t care for sketching or sewing. She had opened her London “house”, with some help from the Duke of Westminster, calling on society ladies to act as models for her catwalk shows. And there was also a brief, unsatisfying foray into Hollywood costuming, after she signed a mega deal with movie mogul Samuel Goldwyn. She dressed the likes of Gloria Swanson and Joan Blondell for movie sets, but her subtle, understated style didn’t translate to the screen. As another New Yorker reporter wrote, she “made a lady look like a lady”, but “Hollywood wants a lady to look like two ladies”.

By the end of the decade, Chanel would shut down operations completely and lay off her workforce: with another world war on the horizon, she claimed it was “no time for fashion”. Before the outbreak of war, she had begun a relationship with Nazi officer Hans Gunther von Dincklage (and kicked off perhaps the most dubious chapter of her life). When the Nazis took Paris in the summer of 1940, she continued to live at the Ritz Hotel, even though it had been taken over by German officials. The following year, Chanel was listed as a trusted Nazi source, and was given an agent number and the code name Westminster, a nod to her former lover. Those connections to British high society made her particularly useful as a potential asset. In late 1943, she became embroiled in an attempt to negotiate with the British, possibly to broker a German surrender: as part of Operation Modelhut, Chanel and her friend Vera Bate Lombardi were sent to the British Embassy in Madrid, with a message directed to Churchill. The scheme came to nothing when Lombardi denounced Chanel as a German agent.

And then there is the ugly matter of her antisemitism. Chanel’s relationship with the Wertheimer brothers was always fraught – she believed that she was entitled to more from the vast success of Les Parfums Chanel, and convinced herself that they had taken advantage of her. When the Germans occupied France, they introduced new laws to ban Jewish people from their businesses. Chanel saw this as an opportunity to bring the perfume business into her control, and tried to use these rules to oust the Wertheimers. They had already outmanouvred her, however. Before fleeing Paris for New York, the brothers had handed over their interests to the French businessman Félix Amiot, and the authorities eventually ruled that the company should stay in his control. The episode is certainly a nasty stain on an already inglorious war record.

Recently unveiled records on display in the V&A’s exhibition complicate matters further, though. They list Mademoiselle Chanel (“dite Coco”) of Rue Cambon as an “occasional agent” for the French Resistance, working with them from the start of 1943 until the following spring; the papers don’t provide details of the work Chanel might have carried out, so we know almost nothing about any potential operations or the acts of subterfuge she might have been involved in. They do, however, associate her with the ERIC network, which had links to British intelligence; the network ceased to exist after April 1944, when its leader René Simonin was arrested. Another document issued by the French government in the Fifties features in the show, too, verifying Chanel’s membership. “The new evidence doesn’t exonerate her,” exhibition curator Oriole Cullen recently told The Guardian. “It only makes the picture more complicated. All we can say is that she was involved with both sides.”

After D-Day, women accused of sleeping with the enemy, the so-called “horizontal collaborators”, were treated brutally, covered in tar, their heads forcibly shaved, and forced to parade though the streets in shame. Chanel did not have to face this humiliation: she was questioned by the Free French for a few hours, but was eventually dismissed; her biographers have speculated that her friendship with Churchill might have played in her favour. In a canny PR move, after the liberation of Paris, she would open her Rue Cambon store to give out free bottles of Chanel No5 to Allied soldiers. This act of reputation management, though, wasn’t enough to turn public opinion around permanently; the taint of collaboration stuck to her, and she would spend years laying low in Switzerland, the doors to Rue Cambon shut. When it emerged that Walter Schellenberg, the Nazi official in charge of Operation Modelhut, was planning to release his memoirs, Chanel coincidentally offered to pay for a home for him and his wife; she would later fund his healthcare, too, and financially supported von Dincklage long after they had split up.

What would eventually draw her back to fashion in 1954, at the venerable age of 70? A stubborn desire to prove a young upstart wrong. “One night at dinner, Christian Dior said a woman could never be a great couturier,” she later told Life magazine. With its full skirts and cinched waists, Dior’s New Look was worlds away from the silhouette Chanel had pioneered decades earlier – and the grande dame of Paris fashion was less than impressed by his efforts. “Dior doesn’t dress women, he upholsters them,” was one acid quip directed at her rival designer; continuing the theme, she claimed that a woman sitting in a Dior dress resembled “an old armchair”.

Her 1954 comeback show (funded, ironically by Pierre Wertheimer) resurrected many of her old style hallmarks, to mixed response from fashion tastemakers; the reaction in her home country was especially muted, thanks to the long shadow of her wartime collaboration. But Chanel ploughed on, probably in no small part motivated by stubbornness, and the next few years brought a flurry of creativity that would eventually win over even her harshest critics. So many of the styles now synonymous with Chanel were launched in this late period: the classic 2.55 quilted bag arrived in 1955, followed by the bouclé tweed suit in 1956 and the two-tone Chanel pumps in 1957. The designer was hands-on until the end: just days before her death in 1971, she was working on her next collection.

Looking back on the first half of her career in an interview with her biographer Paul Morand, Chanel described her career succinctly. “I was there, an opportunity beckoned, and I took it,” she said. Perhaps that’s how to remember her: as the ultimate opportunist, who grasped the moment to secure her own survival, for better or worse.

‘Gabrielle Chanel: Fashion Manifesto’ runs from 16 September until 25 February at London’s Victoria & Albert Museum

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments