The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Why the UK has slipped behind when it comes to cancer survival

As a new report suggests that progress in survival rates is the slowest it’s been for 50 years in the UK, Helen Coffey dives into what went wrong – and why we’re not keeping pace with the rest of Europe

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Cancer survival rates in the UK are the highest they’ve ever been, according to a new report from Cancer Research UK (CRUK). But don’t celebrate just yet – when it comes to progress on cancer survival, the UK has slowed to its lowest rate in 50 years. In the 2000s, the increase in progress was around five times faster than it was during the 2010s.

“It’s worrying that the rate of improvement has slowed in recent years, and cancer patients today face anxious and historically long waits for tests and treatments,” said CRUK’s chief executive, Michelle Mitchell. “Almost one in two people across the UK will get cancer in their lifetime. The number of new cases each year is growing. Beating cancer requires real political leadership and must be a priority for all political parties ahead of a general election.”

Looking at data from the Cancer in the UK report, the annual average increase in the likelihood of surviving cancer for 10 years or more hit an impressive 2.7 per cent in 2000-01; by 2018 this had fallen to 0.6 per cent. In other words: although it’s still getting better, the speed at which it’s getting better has dropped considerably. Of course, like with any field in which progress relies on continual advances being made, there will be ebbs and flows. Perhaps what’s most concerning, though, is that the UK is languishing behind other comparable countries.

Cancer cases in the UK will jump by 37 per cent to almost 625,000 by 2050, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) and the WHO have predicted. It’s a staggering amount more than the average increase forecast for Europe of 22.5 per cent, and is higher than many of our close European neighbours.

Lifestyle is partly to blame; around “40 per cent of cancer cases could be prevented”, said Dr Panagiota Mitrou, director of research, policy and innovation at the World Cancer Research Fund. “UK governments’ failure to prioritise prevention and address key cancer risk factors – like smoking, unhealthy diets, obesity, alcohol and physical inactivity – has in part widened health inequalities.”

Smoking remains the leading cause of cancer in the UK. Cigarettes cause 150 cancer cases every day, and it’s a stark marker of inequality – there are nearly twice as many cases in England’s poorest areas compared to its wealthiest. But cancer rates are different to cancer survival rates. Clearly, prevention is better than cure; yet once someone already has the disease, the UK still lags behind other high-income countries in terms of lowering mortality.

In a large international study published in the Lancet in 2019, the International Cancer Benchmarking Partnership analysed data on 3.9 million people with cancer from 1995 to 2014 in seven countries: Australia, Canada, Denmark, Ireland, New Zealand, Norway and the UK. The study looked at changes in instances and survival for oesophagus, stomach, colon, rectum, pancreas, lung and ovarian cancers. Although survival rates had improved across the seven cancers in the UK, the country had the lowest survival figures for all but two of them (ovarian and oesophageal).

But that’s not because we’re stuck when it comes to scientific breakthroughs, Professor Allan Hackshaw, director of UCL’s Cancer Trials Centre, tells me. “There are some very, very good drugs out there,” he says. “The situation is much better than it was. For example, lung and gastrointestinal cancers had limited treatments 10 years ago – now there’s an array of treatments that can improve survival by six or 12 months. We’re in a good position in having so many of these drugs out there now – and in England, NICE [the body that evaluates new health technologies for NHS use] is quite good at approving new ones quickly.”

However, even with NICE, generally deemed to be efficient and cost-effective, there can be issues. Mark Middleton, head of oncology and a professor of experimental cancer medicine at the University of Oxford, describes the case of a breakthrough new medicine to treat eye melanomas developed by a company near Oxford. It is currently widely used in the US and the rest of Europe – but we’re still debating its use here in the UK. “That’s just a vignette of how things can move that bit more slowly here,” he tells me. “It’s not necessarily a criticism – we need cost-effective care, and not treatment at any price – but we have to be slightly careful that the process doesn’t deprive people of opportunities.”

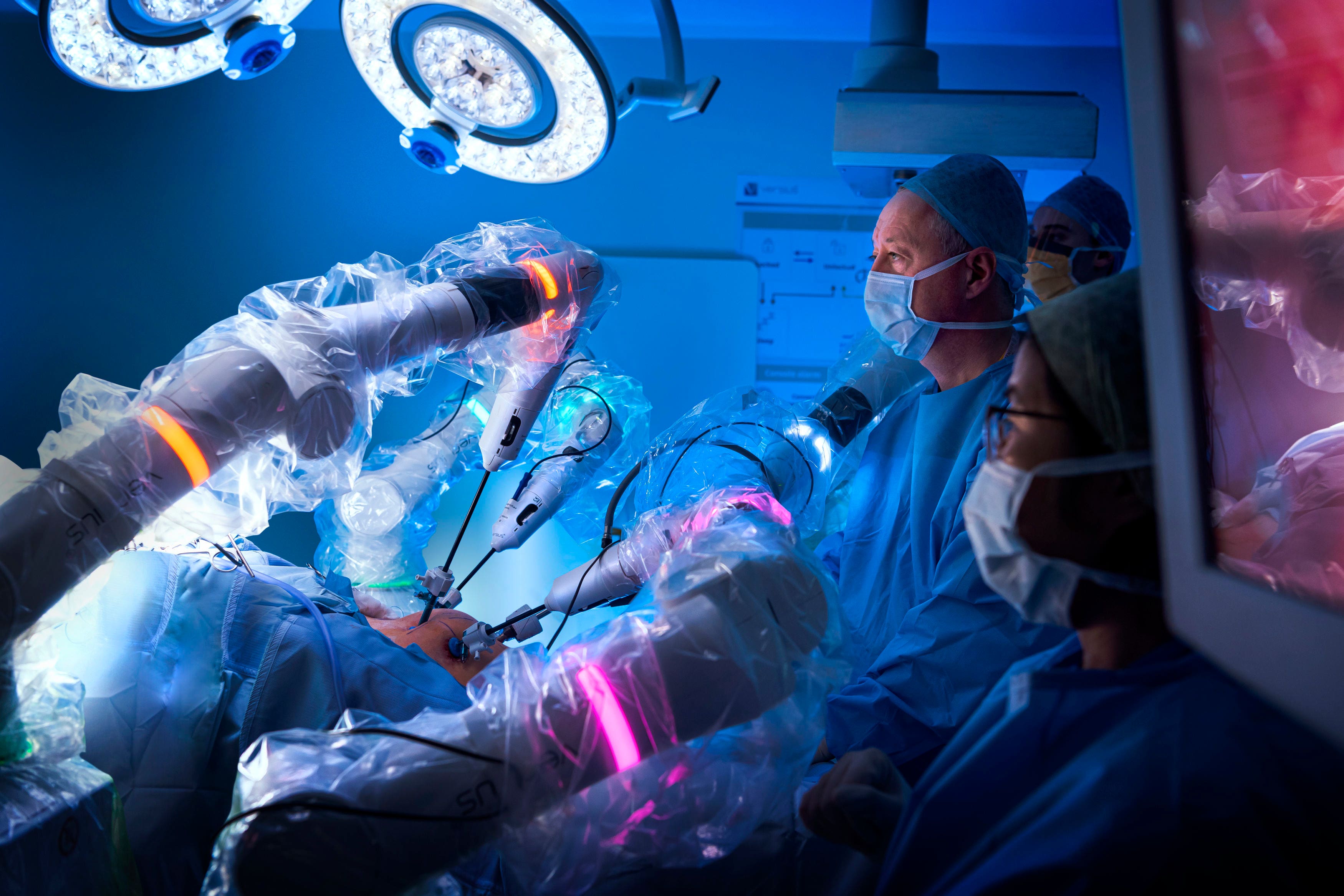

Professor Hackshaw says scientific knowledge is still increasing all the time, citing the discovery that several cancers are not a single entity but are defined by mutations, with targeted drugs to match. Professor Middleton similarly agrees that the UK is making exciting advances in cutting-edge technological innovations, such as robotic surgery.

Scientific knowledge is speeding ahead – it’s now about making sure that the public and the healthcare system are catching up with it

So what, then, is going wrong, if research is surging ahead and creating better cures? There is no easy answer, but Professor Hackshaw puts the slowing of progress down to a couple of major factors: delay in diagnosis and implementation of new treatments. “Our research outfit is pretty impressive, but implementation once something has been shown to work can be slow,” he says. “Access to diagnostics for people referred for cancer can be variable and, once diagnosed, getting access to modern drugs and treatments that are very effective is not as good as it should be.”

Part of the reason behind delayed diagnosis is sufferers themselves; people aren’t always quick off the mark in going to see the doctor when they experience symptoms. “People still think of cancer as a death sentence, unfortunately,” says Professor Hackshaw, and that assumption induces some to bury their head in the sand. “Cancer’s been so well publicised for so many decades to get people’s attention. It’s led to huge amounts of research funding, and that has produced a whole array of treatments that are very effective – but the general public haven’t caught up with that knowledge. For example, smokers automatically think there’s no cure – but there is a high cure rate for early-stage lung cancer these days.”

He adds: “Scientific knowledge is speeding ahead – it’s now about making sure that the public and the healthcare system are catching up with it.”

The UK’s struggle with staffing is causing hold-ups too, resulting in some of the worst waiting times on record. “There are a large number of vacancies in the NHS, including nurses and radiographers,” says Professor Middleton. He doesn’t specifically use the word “Brexit”, but reading between the lines it’s certainly had an impact: “The UK is a less attractive prospect internationally for workers, particularly in the healthcare sector – we used to have a lot of European staff but that’s changed in the last few years.”

We’ve also been slow to adopt innovation, whether it’s drugs, tests, technological advances or new ways of doing things – especially in comparison to other countries. “Sometimes that’s down to money and sometimes that’s down to mindset and culture,” he says. “We have a centralised healthcare system and that’s always going to be slower than if it’s more devolved.”

Falling a little behind other developed nations may not seem cause for alarm right now. The problem is, it’s only going to get worse as cancer cases rise. And they will rise. The UK is predicted to hit half a million diagnoses a year by 2040, around a 20 per cent increase on today’s numbers. Mortality rates are expected to keep dropping, but when the overall rate is going up by that much, the death toll will steadily increase regardless. The IARC and WHO research predicts UK cancer deaths will soar by 53 per cent by 2050.

Somewhat ironically, the uptick in cancer cases is in large part due to successes in other areas – we’re living longer and are less likely to die of heart disease. “We’ve all got to die of something,” as Professor Middleton puts it. “It’s increasingly either from cancer or ‘wearing out’ issues, including dementia. If we lag behind even a little bit when it comes to progress, it’s therefore hugely consequential for the health of the population and how we end up spending our health budget. If we can maximise spending on catching and treating early-stage cancers that we can cure, that’s a hell of a lot cheaper than spending money on looking after people we can’t cure.”

It’s not too late: there are various measures that could help the UK catch up and close the gap. CRUK is calling for a national cancer council, accountable to the prime minister, to create long-term strategies. “We’re also concerned there is a future £1bn research funding gap emerging,” says Sophia Lowes, a senior cancer intelligence manager at CRUK. “The government needs to invest that over the next 10 years in order to keep pace with the current cancer spend per case.”

We’ve had periods where we’ve lagged and periods where we’ve caught up. What’s characterised the periods where we’ve caught up is investment and a plan

Funding is integral to moving forward, agrees Professor Hackshaw, who describes how breast cancer has gone from being “a terrible cancer to get” to “very often curable” thanks to huge amounts of investment. Similarly, improved funding for lung cancer research has seen impressive advances in recent years. He says that more money for currently hard-to-treat cancers, such as brain tumours, will be vital in maintaining momentum. Easier access to early diagnostic screening and tests would be of massive benefit, too, he adds.

But perhaps the most fundamental factor in driving success is strong leadership, something the UK is arguably lacking right now. “We’ve had periods where we’ve lagged and periods where we’ve caught up,” Professor Middleton says. “What’s characterised the periods where we’ve caught up is investment and a plan. In the late 1990s, we had both. Clearly financial times aren’t the same as they were then – we can’t just keep banging the drum for more cash – but clear leadership and stating our priorities is essential.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments