‘It’s an ongoing challenge’: Will the culture wars come for Britain’s books?

Books that discuss race, racism and sexuality are being banned or censored across America, igniting further conflict across the political spectrum. It’s happening in the UK, too, if – so far, at least – to a lesser extent. But should we be worried, asks Francesca Specter

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

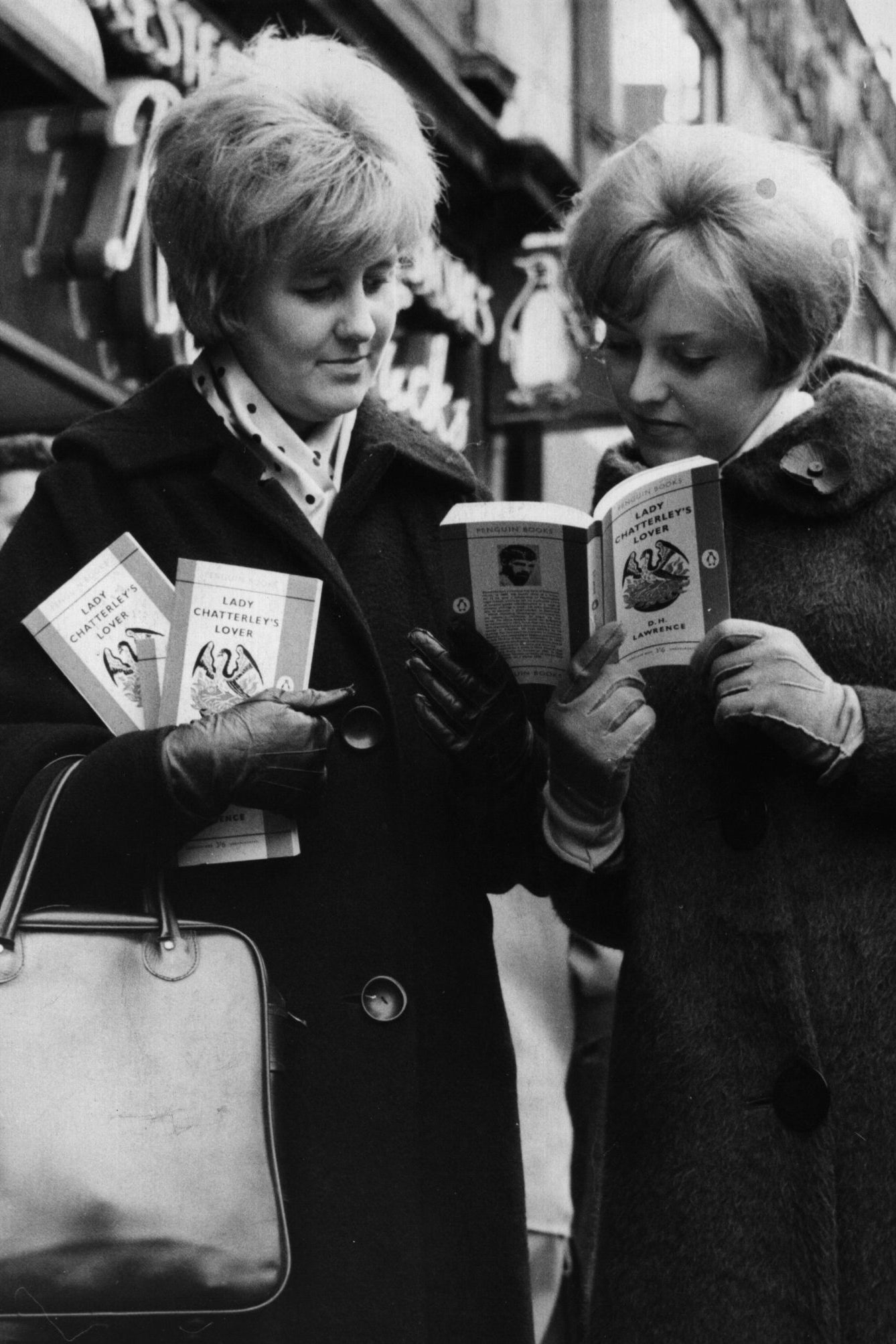

Your support makes all the difference.Is this a book you wish your wife or your servants to read?” asked prosecutor Mervyn Griffith-Jones QC in 1960. Penguin Books were being tried under the Obscenity Act, for publishing an uncensored version of DH Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover. Griffith-Jones’s words quickly backfired, prompting laughter from the jury and an acquittal for Penguin, who sold over three million copies of the book in the following months.

Penguin’s uncensored Lady Chatterley’s Lover was rife with sex scenes, contained explicit language that had not before appeared in a mainstream British novel, and – crucially – was inexpensive and therefore widely accessible (unlike Vladimir Nabokov’s controversial Lolita, which became considerably much more expensive after its unbanning in 1959). According to Sotheby’s, the landmark verdict in favour of Penguin “helped bring to birth a more liberal and permissive Britain”. This spirit seemed to endure over the subsequent decades, but is it under threat today?

Leading voices, including Nick Poole, CEO of the Chartered Institute of Library and Information Professionals (CILIP); Alison Tarrant, Chief Executive of the School Library Association; and Katie Dancey-Downs, assistant editor at Index on Censorship, have expressed their rising concern over requests for book removal in the UK. “We’re worried about the increasing temperature of culture wars,” Poole says, “together with rising parental concern around what children are reading in school libraries.” This concern, adds Tarrant, has been most noticeable “in the past 18 months to two years”.

To get a snapshot of the wider context, Cork City Library was surrounded in September by a human chain of far-right protesters calling for LGBTQ+ books to be removed from its shelves. In the same month, CILIP released a 52-page report encouraging its members to “place principle above personal opinion, and reason above prejudice” and to resist “as far as reasonably possible” requests to remove certain titles from [libraries]”. The report followed research conducted by the organisation the previous year, which found a third of librarians surveyed had been asked to remove or censor books – with 82 per cent of respondents claiming they were concerned about the increase in these requests.

Such trends are filtering into education, too. Over the past year, School Library Association members have reported a rise in “challenges or pressure around certain books that they have in the school library”. Also reported was a rise in cancelled author visits, decisions typically implemented by senior members of teaching staff in response to either parental complaints or those made by staff internally.

An investigation by The Times last summer found a number of universities had withdrawn certain books from their course lists – or made them optional – due to “challenging” material. This includes the University of Sussex, which withdrew from its curriculum August Strindberg’s play, Miss Julie, due to suicide themes. This is not an approach that Poole endorses: “One should err on the side of not banning things. Our general view as a profession is that it’s better for the reader to access material, but to be able to understand the basis on which that material is problematic. It’s about presenting it within a context.”

Libraries have been hit upon as a useful political lever for protests. We’re concerned about that because no library staff should be fearful for their safety when they’re going into work

Meanwhile, British authors such as Jacqueline Wilson and Anthony Horowitz have expressed their own concerns over book censorship. In Wilson’s case, this was in response to the prospect of US-style children’s book censorship over race and LGBTQ+ issues coming to the UK, which she called a “huge worry… We are not America, but we do follow American trends”. Horowitz’s critique centred around the posthumous editing of authors’ books, most notably the new editions of Roald Dahl books released by Puffin – which have been rewritten to exclude language that might be considered offensive, such as the word “fat” (publishers Puffin have since announced their intention to keep both original and new editions available to readers).

When you consider the current landscape of censorship, it is hard not to speculate (as Wilson has) that what’s happening in the US might be prescient for the UK. Earlier this month, the singer Pink hit headlines when, at her concerts in Florida, she handed out 2,000 free copies of books that had been “banned” at some of the state’s schools. Florida, according to PEN America – has censored or restricted almost 40 per cent more books than any other US state, while the same organisation reports that US-wide public school book bans have risen 33 per cent in the past year. This nationwide-censorship row – driven by right-wing political groups – is also affecting community libraries, with conversations revolving around books with themes of LGBTQ+ issues, race and racism.

And yet, we must be careful when making these geographic comparisons. One reason for caution is to avoid creating a self-fulfilling prophecy, whereby attention on US book bans creates a copycat effect over here. “The steep rise in book bans in the USA may well embolden people who would like to see such books removed from UK shelves,” says Dancey-Downs.

Although we might well see echoes in the culture wars taking place on both sides of the Atlantic, “the US is a very particular context,” Poole stresses, “with distinct politics and economics”. For instance, at the centre of the US row is Florida’s Parental Rights in Education Act, which limits teaching about gender and sexuality in schools.

The UK is distinct, not only in its politics but also in the way it reports book censorship. The US, notes Dancey-Downs, has “mechanisms for monitoring book challenges and book bans, which we simply don’t have in the UK”. One example is the American Library Association’s monitoring of public requests to censor library materials – the eventual data is then released to the press.

There is no UK equivalent whereby national data about book censorship requests is made available (the CILIP survey of librarians cited above, which noted an increase of public requests, was informed by the reported experience of respondents in their local areas). This absence isn’t, it appears, an oversight, but rather a national policy. Whether or not it’s the right one is a crucial debate at the heart of the book censorship conversation.

Publicising data can be a double-edged sword. Tarrant is of the view that “if we were to release a list of books that had been challenged, that would, for some people, become a list of books that ‘should’ be challenged. It’s very difficult to collect the data without putting our members at risk, or adding fuel to the fire”. This is an inverted version of what’s known as the “Streisand Effect”, whereby censorship backfires and makes the target more popular; in this context, highlighting censorship could offer, as Dancey-Downs (who echoes Tarrant’s concern) puts it, “a list of targets to would-be censors”.

But is the UK at risk of underrepresenting the problem? Particularly if removal requests continue to increase in a way our system often fails to quantify. “I think this is one of those situations where you can’t win,’ admits Tarrant. “It’s an ongoing challenge.” Dancey-Downs adds: “Ultimately, it’s vital to shine a spotlight on censorship and make sure the right support is put in place as early as possible. Without doing that, we risk the problem growing behind closed doors.”

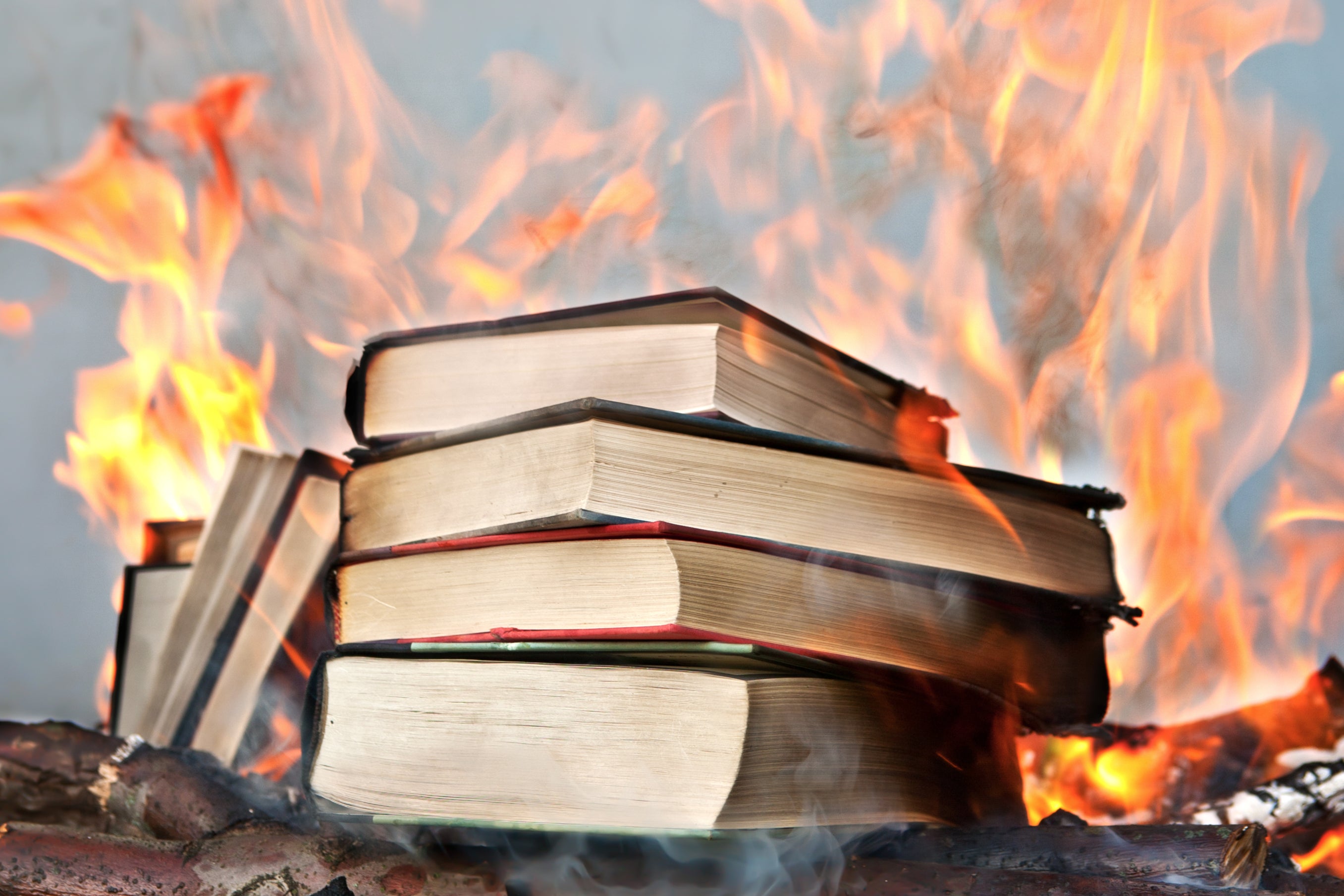

What we don’t have – and this is perhaps true of the US as well – is the kind of high-profile censorship row that surrounded the uncensored 1960 edition of Lady Chatterley’s Lover. Lawrence’s book The Rainbow was also suppressed and put on trial in 1915, and subsequently 1,011 copies were seized and burnt. James Hanley’s Boy was also banned under the Obscene Publications Act from 1935 until 1991 (other examples of banned books include James Joyce’s Ulysses, banned in the UK until 1936, and Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita, banned in the UK between 1955 and 1959).

In our contemporary climate, there are some isolated instances of Amazon stepping in to ban the circulation of certain books, such as English Defence League co-founder Tommy Robinson’s book Mohammed’s Koran: Why Muslims Kill for Islam, which was removed by the platform in 2019 after being deemed “inappropriate content”. However, instances of government book bans or censorship remain virtually unheard of in modern day UK, clarifies Poole.

Meanwhile, what is happening is a subtle, but nevertheless troubling to some, form of suppression of certain texts and authors in schools. Tarrant says: “Some of our members are being told, ‘You can have that book in the library, but don’t include it in the display, or let’s just leave it off this year’s reading list [a list of recommended reading compiled by school librarians]’.” She describes such policies as “insidious and hard to spot”. For Tarrant, cancelled author visits fall into the same category. A high-profile incident happened last year, when Simon James Green, a gay author, was disinvited from speaking at a Croydon-based Catholic boys’ secondary in response to demands from school leaders.

Then there’s the trial by media of certain books and authors. Take the phenomenon of the “Twitter pile-on” (whereby an individual user of X formerly known as Twitter receives an avalanche of critical messages), which is said to be particularly rife within the young adult fiction market. “Teen Fiction Twitter Is Eating Its Young”, read a 2019 headline in libertarian magazine, Reason. Earlier this year, author Elizabeth Gilbert decided to “indefinitely” delay publication of her novel, The Show Forest, which chronicles a Russian family’s escape from Bolshevik Russia to Siberia, out of sensitivity for the ongoing Russia-Ukraine war. Although Gilbert issued a video statement saying “it is not the time for this book to be published,” what’s notable is that the decision followed a “review bombing” of the recently-announced title on Goodreads – whereby users coordinate to post negative reviews. It has received a mixed response – with some praising the decision, others worrying about the precedent it may set; in a statement, PEN America CEO Suzanne Nossel called the decision “well-intentioned” but “regrettable”.

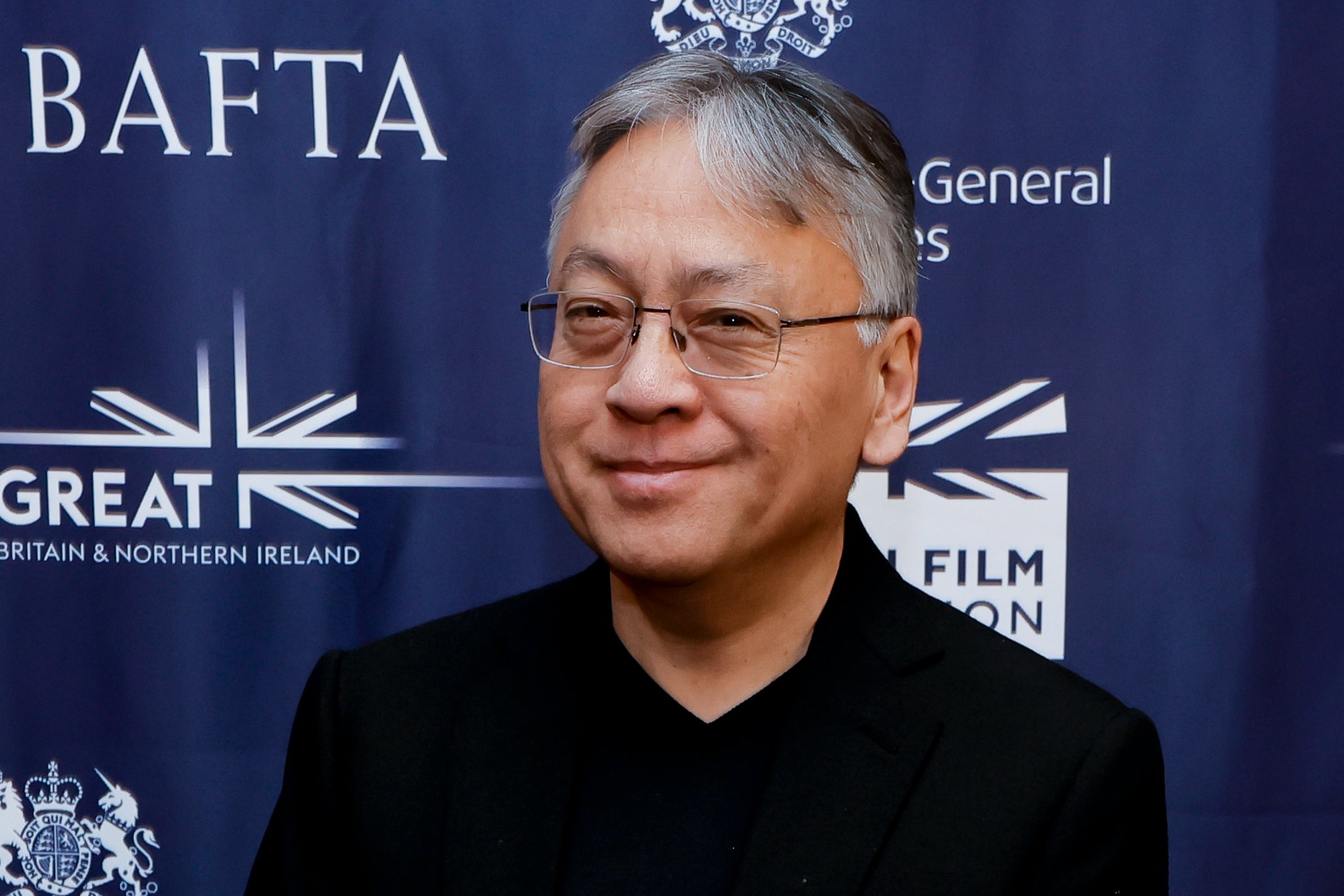

While Gilbert is American, leading British figures have expressed concern that UK authors would be similarly affected, including British-Japanese Nobel Prize for Literature winner Sir Kazuo Ishiguro. “I very much fear for the younger generation of writers,” he told the BBC in 2021, whom he suggests live “under a climate of fear… [that] an anonymous lynch mob will turn up online and make their lives a misery.” When asked about Ishiguro’s comments, during a hearing at the House of Lords later that year, Hachette CEO David Shelley responded, “Social media platforms absolutely have a hold of all of us and are influencing decision-making in all spheres of life in a very big way. More of a light needs to be shone on to that.”

James Gray, marketing and advocacy manager at Libraries Connected, takes a more optimistic view, arguing that “most Britons, and therefore most library users, aren’t particularly animated by culture war issues, so we should be careful not to overstate the problem.” With regards to public libraries, he says: “There’s a big difference between being asked to remove or censor something, and actually doing it. As long as something is published and available legally in this country, then libraries will allow people to access it. While it’s fair to say there’s been a rise in removal requests, our library service members are committed to anti-censorship guidelines.” He adds that no library will ever have room to stock every single book: “If older versions of any book are removed from the shelves and the newer versions put there instead, it’s not to do with censorship, it’s just stock rotation.”

What industry officials do agree on is twofold. Firstly, librarians should not be made a target of any ongoing culture wars around books. “Libraries have been hit upon as a useful political lever for protests,” says Poole. “We’re concerned about that because no library staff should be fearful for their safety when they’re going into work.” And secondly, equal access to books and reading materials, with a diverse representation of characters and themes, is paramount.

“As librarians, we are trying to keep hold of our fundamental belief,” Poole says. “[That] everybody, everywhere, has a right to access books and learning.”

This article was amended on 6 December 2023. It originally stated that the University of Essex had permanently removed The Underground Railroad, but this was inaccurate. The book was removed from one reading list, but remains widely available in the university and is an option for future reading lists.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments