The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Loved in triangles, dressed for liberation: The queer fashion secrets of Virginia Woolf and the Bloomsbury Group

The famous literary circle – composed of creatives such as Woolf, her artist sister Vanessa Bell and novelist EM Forster – has taken on a somewhat dowdy image in our cultural conscience, writes Patrick Sproull. But a revealing new book and exhibition unearth deeper meanings to their sartorial choices

When Dorothy Parker described the Bloomsbury Group as having “lived in squares, painted in circles, and loved in triangles”, she didn’t say anything about how they dressed. There’s a good reason for that. When most people think of the Bloomsbury Group, the informal assemblage of artists, poets and writers established in the early 1900s, we think of their art, their cultural clout, their influence, their incestuousness. What they wore has seldom featured prominently in their legacy. The acclaimed fashion journalist Charlie Porter, though, is eager to rectify that with his excellent new book Bring No Clothes: Bloomsbury and the Philosophy of Fashion.

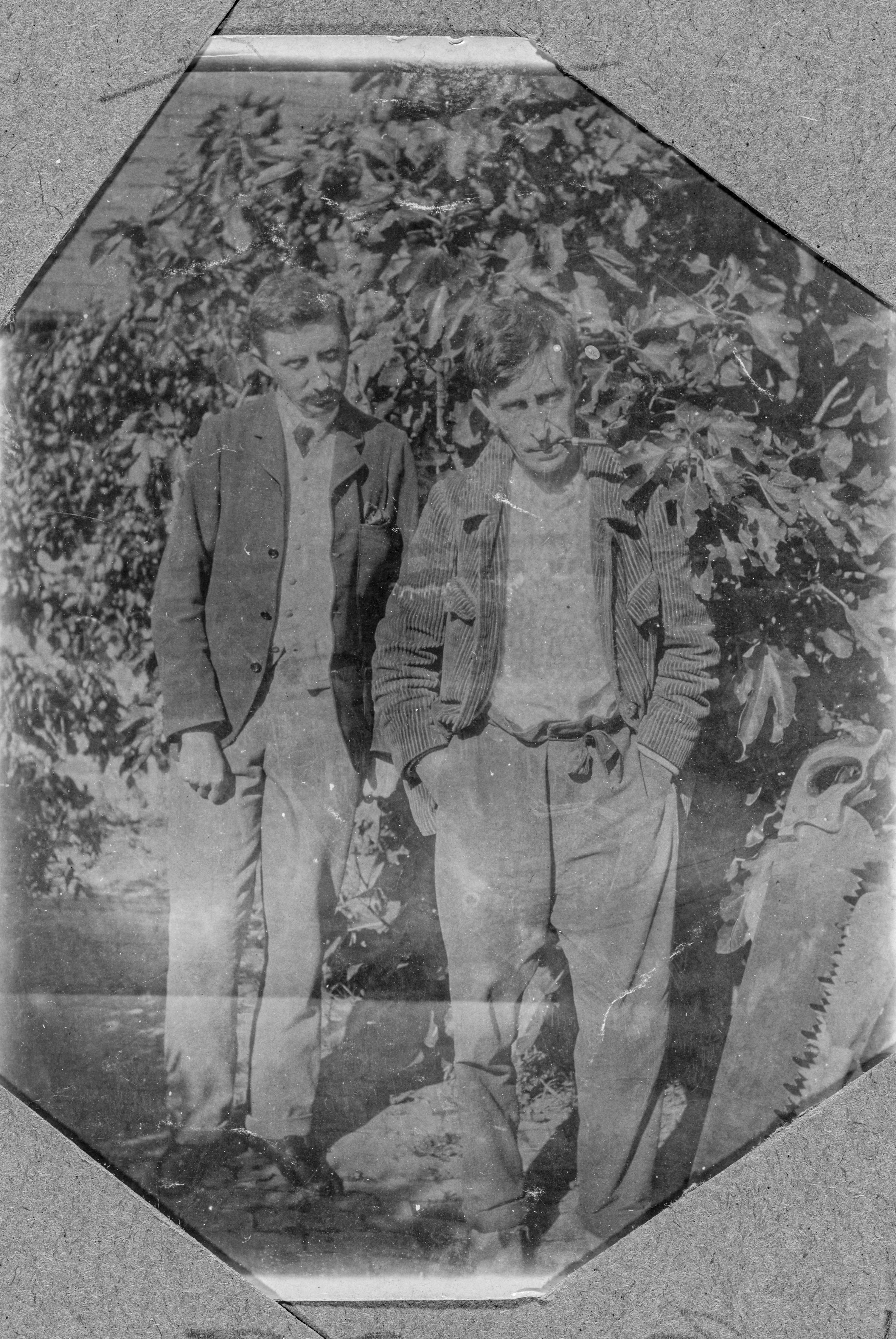

Among the Group’s numbers were Virginia Woolf, her sister Vanessa Bell, author EM Forster as well as economist John Maynard Keynes and the painter Duncan Grant. Their heady existence in the early 1900s is an early example of an enviably cosmopolitan literary social scene that was popularised in the latter half of the century by American writers like Truman Capote and James Baldwin. Their clubhouse was the East Sussex farmhouse, Charleston, and in conjunction with Porter’s book, an exhibition, Bring No Clothes: Bloomsbury and Fashion, opens this month at Charleston’s new gallery in Lewes. The exhibition will draw together original items worn by its members as well as pieces inspired by the Group from contemporary fashion houses, such as Commes des Garcons and Dior.

The more famous members of the group, authors Woolf and Forster, have taken on somewhat dowdy images in our cultural conscience, arising from a presumption that because they were so dexterous with words, they couldn’t have a similar command of their wardrobe. Porter, admittedly, is not out to claim that someone like Virginia Woolf was actually a Coco Chanel-esque style maven. But her clothes shouldn’t be dismissed; instead, they are simply another avenue to explore her well-documented complicated genius.

“The thing with clothes is that it allows you to get close to an individual and it allows you to get close to their experience,” Porter says. “By looking at their clothes, in particular their actions and what they did at the point where Bloomsbury formed, what emerges is this sense of queer humans and their allies attempting to live life.”

That sense of the Bloomsbury Group as a coterie of queer (and queer adjacent) artists forms the main, most vital artery of Bring No Clothes. Porter’s generous, empathetic eye feels like a corrective for the more salacious historical depictions of the Group’s affairs.

“Because they’re upper class it’s [seen as possessing] this poshness or eccentricity, and as soon as something becomes titillation it casts queer people as purely people whose lives are there for entertainment value,” Porter says. “By starting with their clothes, it allows you to be with them and talk about them in non-prurient ways.”

I think their clothes allow you to look at their literature or art or political and economic thinking with honesty and clear, fresh eyes

As children, Woolf and Bell experienced abuse from their father and half-brother, and they were repressed, like so many women of the time, by constrictive Victorian attire, cinched and pulled and tightened into submission. In adulthood, they found freedom in more liberating clothes: flowing summer dresses, outsized knitted cardigans, long, loose overcoats.

They experimented with pattern and colour, and Bell even made her own clothes, often using safety pins to secure garments. Safety pins have now become an enduring staple in contemporary fashion, used by Vivienne Westwood, Jean Paul Gaultier and John Galliano. When safety pins first gained prominence under Westwood, they were a sign of punkish rebellion. That’s precisely how Bell used them at the time; breaking conventions on how fashion operates and telegraphing her own queerness.

Porter dedicates considerable time to the men of the Bloomsbury Group and what their fashion tells us. Having written mostly about menswear, he notes that the vast majority of fashion journalism focuses on women’s clothing. “If there are any stories on the clothes that men wear, it’s normally mocking,” he says. Like when Barack Obama wore a tan-coloured suit and had Fox News enraged for weeks. Or when Emmanuel Macron was photographed with his shirt unbuttoned to reveal his chest hair.

“What that actually covers up is that the patriarchal hold of tailoring is so strong, you’re not meant to question it,” he says. “It never changes. It’s a language of power that’s so entrenched that those in power who wear suits see it as facile to even talk about what they’re wearing. If you question it, it starts to chip away at their patriarchal power.”

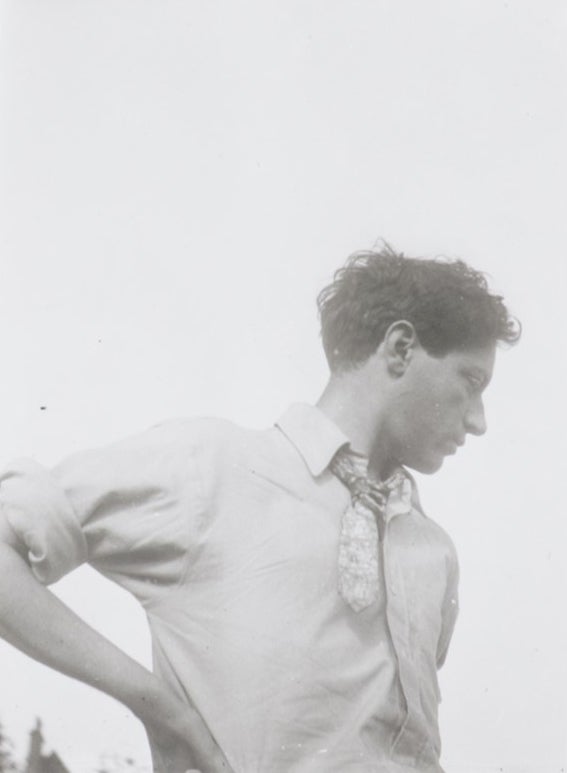

Porter is a queer man, and his empathy for the Bloomsbury Group’s men makes for the book’s strongest passages. Within the confines of men’s clothing – simple, rigid, unforgiving – the painter Duncan Grant found ways to display his true self; he would wear a vest top hanging off one shoulder, exposing his nipple in an undoubtedly feminising gesture. On other occasions, he would wear a shirt and tie knotted into a messy, unkempt stub, thumbing his nose at the refined presentation expected from men. Sometimes Grant would simply wear nothing at all, as he was frequently photographed naked.

If Grant is an example of a queer man completely unburdened by societal expectations, his obverse is EM Forster, the author known for Howards End and A Room with a View. There was a man whose body was for no one but himself, tightly hidden under cotton and wool suits. Forster’s entire life was constrained by homophobia; his greatest, queerest work, the gay love story Maurice, was written between 1913 and 1914 but not published until 1971. Forster’s presentation, in the model of the neat, prim English gentleman, was a tourniquet for his queer identity, much like any inhibitive corset.

Porter’s treatise on the clothes of the Bloomsbury Group feels like it doesn’t just introduce a new frame of thinking, it adds a fresh layer of humanity to the collective. He approaches them like peers, offering theories and speculation he admits could be wrong, but his level of thoughtfulness and care would have you believe it all. Porter is aware that fashion can often serve as a distraction – he comments on a shallow reading of the Group that he finds “completely uninteresting”, that of the so-called “Bloomsbury look”, an imprecise, gift shop-ready understanding of their aesthetic. “Anyone can look at a photo and copy it,” he says. “It’s not interesting.”

It’s not just the Group that has fallen victim to reductionism – think of Frida Kahlo socks, Van Gogh magnets or Sylvia Plath tote bags. Yes, it’s entirely possible to patronise an artist’s talent through their clothes, but only if you lack the capability to understand that clothes are an essential part of their identity and offer more than mere aesthetic value. I mention to Porter a recent profile of Zadie Smith in Vogue, where the novelist was vividly photographed wearing Alexander McQueen and Maison Margiela. Allowing Smith the opportunity to express herself away from the page doesn’t diminish her writing, and clothes can often be as important a way to access a person’s complexities as their art or writing.

“I think their clothes allow you to look at their literature or art or political and economic thinking with honesty and clear, fresh eyes, rather than layers of academic thinking,” Porter says. “For me, it’s expansive, not reductive.”

‘Bring No Clothes: Bloomsbury and the Philosophy of Fashion’ by Charlie Porter is out now. Bring No Clothes: Bloomsbury and Fashion is at Charleston in Lewes from 13 September

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments