The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Were the Nineties really so good?

As teenagers on TikTok pine for a decade they only know from film and television – and Netflix launches a sitcom sequel, ‘That ’90s Show’ – Eloise Hendy speaks to experts and real-life Gen X-ers about the most misunderstood of eras

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.For today’s teenagers, nothing is cooler than the stuff that was cool 30 years ago. Tamagotchis. Flip phones. Keanu Reeves. Across TikTok, young people born long after the millennium are creating videos imagining “being a teenager in the Nineties”. Dancing to Alice Deejay club mixes, they envisage a wonderful, remote age of “no social media,” “no meaningless distractions,” “just you and your friends talking for hours”. Three decades on, the cultural products that came to define the Nineties have taken on a new glow: the rosy hue of nostalgia. Curious, alluring, strange. As one TikTokker put it, “it wasn’t all rainbows and sunshine. But it’s nice to think about it that way.”

This week, yet another show that was a cultural touchstone in the Nineties and early Noughties is “returning” to screens in spin-off form. That ’70s Show – the coming of age sitcom set in Seventies Wisconsin – is now That ’90s Show. Basement-dwelling, weed-smoking teens remain, but instead of Ashton Kutcher and Mila Kunis adorned with bell bottoms and feathered hair, now the Point Place adolescents – and the kids of the original show’s leads – are donning checked shirts and backwards baseball caps, and drinking out of red Solo cups. The Independent’s Nick Hilton has already dubbed it “edgeless and unthreatening”, while another critic called it “a nostalgia turducken” – the Seventies nostalgia that launched the original show now layered within nostalgia for that show and for the era when it first aired, like a series of birds stuffed in bigger birds.

The whole premise of the show, and its appeal, seems akin to all the “imagine being a teenager in the Nineties” TikToks. Lindsey Turner – the daughter of the original series’ creators Bonnie and Terry Turner and an executive producer on the reboot alongside them – has said the Nineties “was the last time that people were looking up; they weren’t looking down at their phones”. She describes the decade as the final era for “a real kind of engagement, having to make your own fun and really connecting with each other”.

Yet while the image of a more engaged era is undeniably enticing, is it actually true? Were teenagers “looking up” back then, and paying attention to the world in a way teenagers now are unable to? Or is it just “nice to think about”?

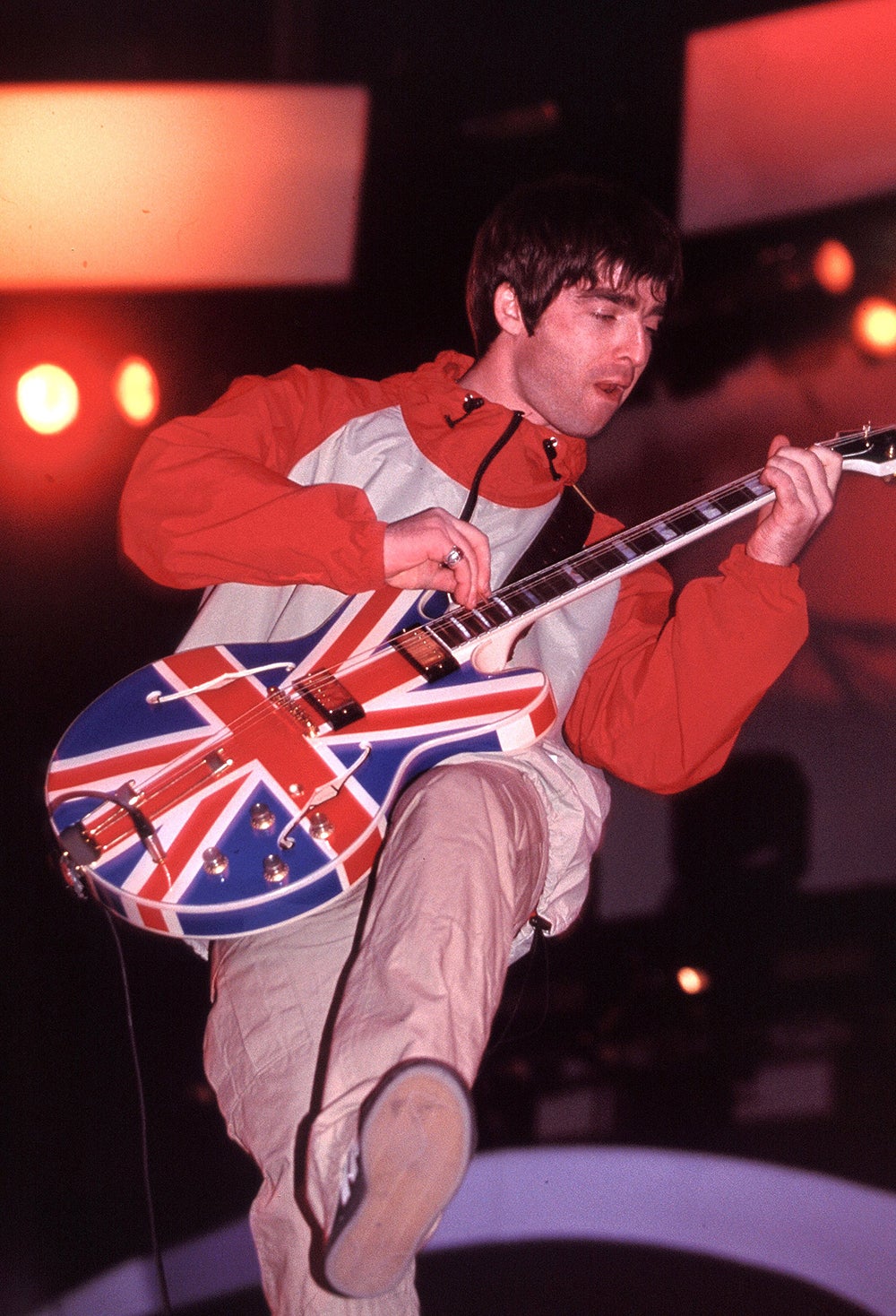

Caroline Jones turned 12 in 1990. A “big gig-goer” in the Britpop scene, she recalls the decade as a more optimistic time. “It certainly felt like you were in the moment more,” she says. “[There were] no mobile phones until I got to art college in 1998, though the phones weren’t very advanced and it was just to send SMS on a Nokia.” Anna Waletzko, a behavioural analyst at Canvas8, also links the mood of the era to the communication restrictions of early mobiles. “Remember flip phones? There’s something satisfying about the way a flip phone snaps shut,” she says. “When you’ve closed it, you’re done checking it for a while – the clamshell design offers a sort of finality.”

“It wasn’t until the late Nineties that my family actually bought a computer,” Vanessa Gordon notes. Now the CEO and publisher of East End Taste magazine, Gordon recalls understanding the internet as “this entity that was developing”. But, she says, “we didn’t think too much about it.” What instead defined her teenage years were physical spaces. “I remember [that] going to the mall was such a big deal. Going out to the movies, hanging out at the arcade, meeting friends for coffee at the local bookstore… I really do cherish that time in my life.”

There were huge problems in the Nineties that tend to be airbrushed from popular memory

Creative consultant Giada del Drago was an art student at Central Saint Martins in the Nineties, and also remembers “a lot of daydreaming and a lack of technology”. She characterises the era as “a time of making do and dreaming big”. Reminiscing about cutting all her hair off and shapeshifting “from a grunge rock loving emo hippie to a raver cyberpunk,” Del Drago recalls buying two tickets to a rave at Brixton Academy. “I decided that I would invite the first cool person I met at college to come with me.” Yet, while this might sound very cool to contemporary teenage ears, Del Drago says making connections was actually quite challenging. “You had to work hard to find kindred spirits and ended up hanging out with people who were not actually into the same things as you. They were people in your class or at your work.” Rather than making people less connected and engaged, she suggests social media makes it easier to “really find or stay connected to your tribe”.

Andy Hill became a teenager in 1993 and now works as a writer and ghostwriter. Despite suggesting that “people seemed to get less wound up about politics” in the Nineties, and describing offline teenage conversations “about football or The Simpsons” as “blissful,” he also believes it’s “easier to stay in touch with friends” in the smartphone era. “I think screens everywhere are an improvement,” he says. “As a shy late teen in the Nineties, I used to lay awake in my North London bedroom thinking ‘there must be girls around here who’d potentially be interested in me. One day maybe technology will figure that out and help me meet them’.” Now, with dating apps and social media platforms quite literally at our fingertips, Hill thinks there might be “less loneliness” than before.

Alex Strang is the insights editor at Canvas8. He stresses that “nostalgia is a powerful tool,” and narratives about the “good old days” often don’t take into account the whole picture. “Just because a period of time looks purer through the lens of Nineties movies, music videos, or even just the aesthetic, [it] doesn’t mean it actually was. People that were actually around in the Nineties would argue that kids might not have been looking down at smartphones [but many] were definitely looking down at GameBoys, still stuck in their rooms playing on consoles.” So, is the idea that the pre-smartphone age was “the last time that people were looking up” just a myth?

Dr Neil Ewen is a senior lecturer in communications at the University of Exeter, and has noticed that many of his students have started “wearing the same Nirvana T-shirts that I wore as a teenager back before Kurt Cobain died and grunge burnt out”. He doesn’t think this is particularly unusual, though. Since the birth of teenage culture in the Fifties, “trends have emerged in popular culture, saturated the market, and then disappeared – only to reappear again years later.” Yet he also stresses that the Nineties have particular resonance: “First, it’s quite clearly the end point of one era (the offline era) and the starting point of a new era (the networked society), and second, it’s often considered as the last time the world wasn’t falling apart.”

In the Nineties, Dr Ewen suggests many theorists imagined new technologies “would set us free and create a new utopian world where work would be automated and people would have more free time for relaxation and creativity”. Today, of course, this has been proven to be a pipe dream. “Rather than setting us free, digital tech and social media platforms are often seen to have created regimes of surveillance that create anxiety.” As Dr Ewen stresses, we are now “living through an extended crisis of capitalism, where the economy is managed by and is only working for the one per cent, while the majority of ordinary people are finding everyday life increasingly difficult and basic public services have been defunded and run into the ground.” In this context, he says “it’s easy to see why there’s been a rise in nostalgia for the Nineties – a decade of relative peace and prosperity when there was still hope for the future.”

Though Dr Ewen is also keen to puncture this rose-tinted view of the past. “If you were poor or part of a marginalised community, [the Nineties] weren’t a bed of roses.” More than that, he emphasises “there were huge problems in the Nineties that tend to be airbrushed from popular memory,” and cites the Yugoslav War, the Rwandan genocide, IRA bombings, and the Rodney King beating. Rather than reflecting reality, then, Dr Ewen suggests “nostalgia tends to create a fantasy past as a coping mechanism to deal with the problems of the present”.

Dr Agnes Arnold-Forster is a historian of medicine, healthcare and emotions, and is currently writing a book about nostalgia. She says a common explanation for the current Nineties “nostalgia wave” is that “political polarisation and the pandemic are supposed to have unsettled people, prompting them to return to the Nineties in search of stability”. Yet, she urges that we should be sceptical of this analysis. Noting that “not only have these ‘nostalgia waves’ been an almost ever-present feature of society and cultural commentary since at least the 1970s,” she suggests “the argument that people are turning to the Nineties because the 2020s are somehow dissatisfactory” mischaracterises both that decade, and what came after. Rather than considering the current nostalgic trend “as a product of a contemporary malaise,” Dr Arnold-Foster urges, “we should see it as a consequence of commercialisation and the press”.

“The re-release of Nineties fashion, TV programmes, and films is as much about relying on what we know has worked before, what has sold and made money previously, and can anticipate might appeal again,” she argues. Simply put, nostalgia not only soothes, but sells.

Visions of the decade as a more connected, engaged, or somehow “purer” time might suit Netflix reboots, then, but aren’t really rooted in reality. “Life wasn’t easier in the pre-internet age,” Strang says. “That’s a myth. Without the internet, it was more difficult to hear about, deal with and make a record of anybody’s problems other than your own.”

‘That ’90s Show’ is streaming on Netflix now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments