Learn to Live: Student who fled Syria explains how education offers hope to young people in war zones

'When I left the exam, the scene was terrible. There was a river of blood going down the street'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A PhD student who fled Syria to study in the UK has spoken of the importance of education in giving young people hope in war zones.

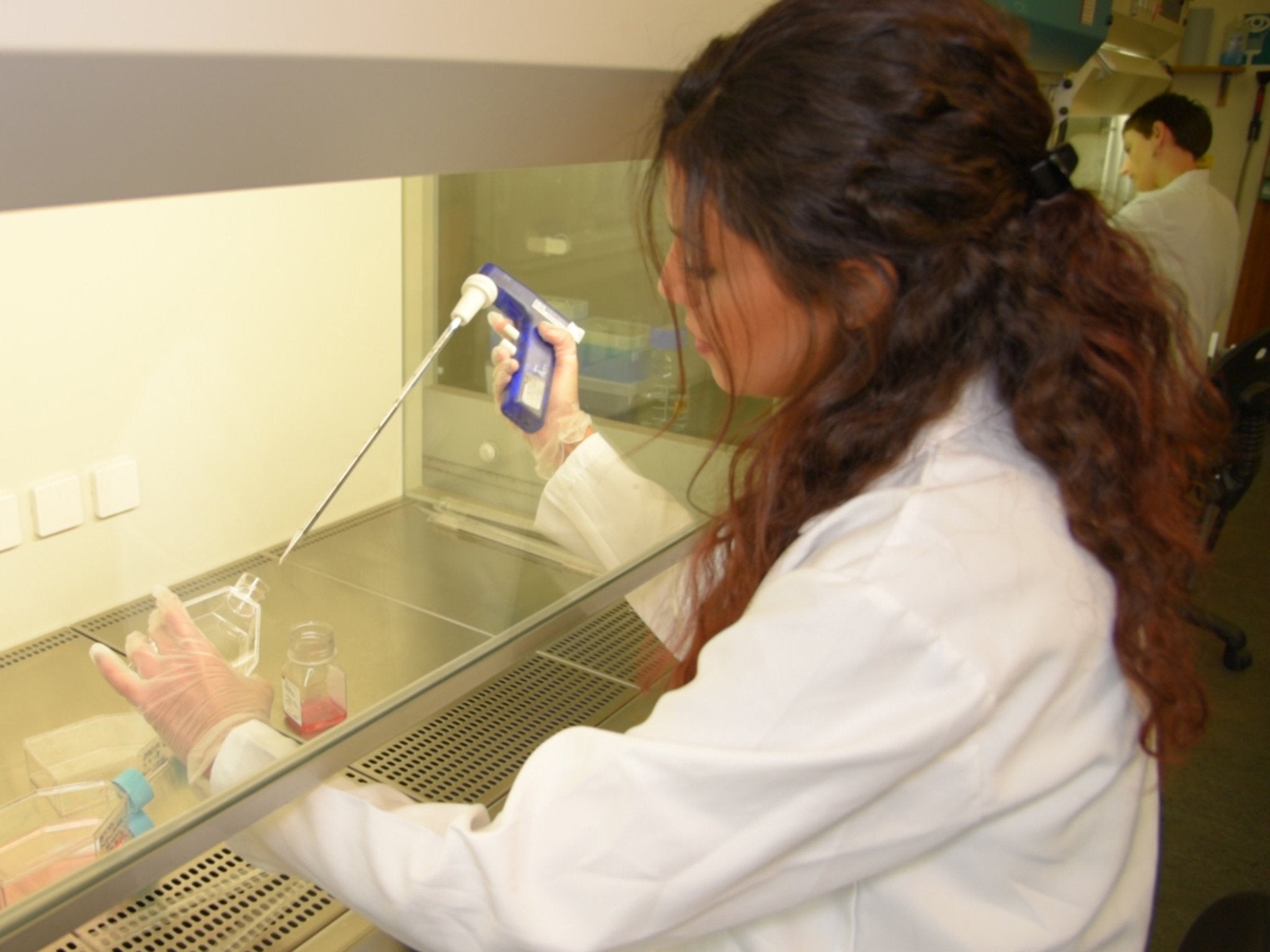

Yara Issa*, 28, is carrying out cancer research at the University of East Anglia (UEA) in Norwich – and she is hoping to help develop medicines that will reduce or prevent cancer.

But she recalls how her university building in Aleppo was hit by a bomb while she was sitting a pharmacy exam. The glass window shattered and her friends were left injured by the blast.

Yara made the decision to stay and sit the test despite the chaos unravelling nearby. She did not want to delay getting her degree by missing the exam.

“I finished it but it was a nightmare,” she says. “When I left the building, the scene was terrible. There was a river of blood going down the street. There were ambulances and a lot of screaming.”

Yara was in the middle of her pharmacy degree when the fighting broke out. She kept her head down and persevered with her work despite losing both her friends and her home to the war.

“In order to do anything in the future I had to survive this time,” she says. “It was merely the fact that ‘I am going to finish my degree’ that kept me going.”

Yara was finally able to escape Syria when the Asfari Foundation offered her a scholarship for a masters in the UK – which led to her PhD.

But Yara – who was trying to apply for courses abroad with no electricity, heating and limited internet in her home – faced a number of rejections before being given a chance.

“If I didn’t wake up in the morning and realise I didn’t have anywhere to go in my life – apart from applying and trying to find a legal way of leaving the country to continue my passion for higher education – I would not have been able to leave,” she says.

Yara is determined to do more to help other young refugees who are determined to get an education and is now a youth advocate for War Child, the charity working with The Independent on our Learn to Live campaign.

The campaign, in conjunction with the Evening Standard, aims to forge links between students in the UK and their peers who are living in war zones and refugee camps across the world. It is hoped the campaign will increase empathy and understanding of the issues facing young people in different parts of the world.

We are linking schools in the UK with schools in countries like Jordan, Iraq and the Central African Republic to let children whose lives have been devastated by war know that neither they nor the importance of their education have been forgotten.

Yara says: “Providing Syrian children with safety, education, mental and psychosocial support could prevent detrimental long-term effects both in the countries hosting Syrians and Syria itself.”

The transition from Syria to rural England was not easy, however. When she first came to the UK to study three-and-a-half years ago, Yara says she found the experience “shocking and scary”.

“It was a different universe,” she says. “At the beginning, I didn’t feel like people had empathy or understanding. But I don’t blame them. For me, I was a shy person.

“It was the shock because I came from a different place, from a war zone. But once I interacted and learned more about what they like to eat and where they like to dine, it went really well.”

*Her name has been changed to protect her identity

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments