Who is Yoshihide Suga, Japan’s new prime minister?

Can ‘Uncle Reiwa’, the veteran shadow power behind the departing Shinzo Abe, handle the political limelight himself? Ben Chu reports

The new leader of the world’s third largest economy was, until recently, an obscure figure even in Japanese politics.

Yoshihide Suga had worked his way up to the influential position of Chief Cabinet Secretary – a sort of cross between deputy prime minister and chief of staff – largely without trace, failing to build any kind of media profile.

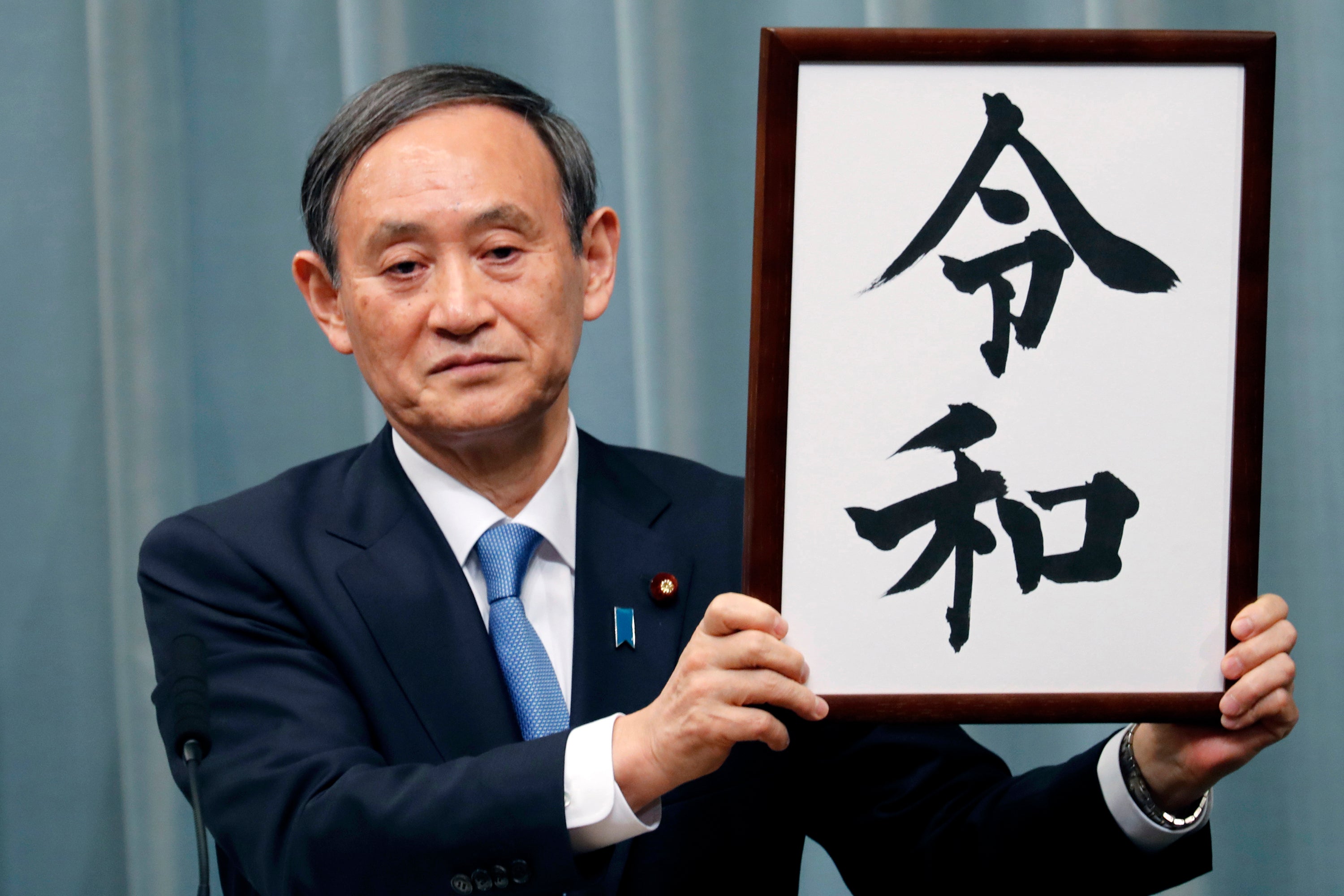

That changed dramatically on 1 April 2019 when it fell to Suga, in his role of Cabinet Secretary, to unveil to the public, live on national television, the official name chosen for Japan’s new “era”, beginning with the accession of Crown Prince Naruhito to the Chrysanthemum Throne.

“The name of the new era is ‘Reiwa’,” Suga declared, holding up a board with the strokes of calligraphy which represent the words “beautiful harmony”.

From then on “Uncle Reiwa”, as he became known, was a household face in Japan.

Yet, even then, few expected the 71-year-old to succeed Shinzo Abe as leader of the dominant Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) when the current prime minister announced last month that he would be stepping down early because of a chronic health problem.

Suga is not associated with any of the powerful factions within the LDP, which has controlled Japan’s government for every year but four since the Second World War.

But Suga’s better-known LDP rivals failed to pick up sufficient support, leaving the 71-year-old Suga to march to victory in the leadership election this week .

Though he may have risen without trace, it would be wrong to say Suga hasn’t left a mark.

For the past eight years, Shinzo Abe has striven to shake Japan out of its two-decade economic torpor with a radical programme of monetary stimulus, higher public spending and restructuring. Suga has been Abe’s right-hand man through it all.

Unlike so many Japanese politicians (Abe among them) Suga does not hail from a political dynasty.

He was born in 1948 to a family of modest strawberry farmers in the Akita prefecture of north Japan. He was an unexceptional student at school and his family’s lack of money meant he had to work his way through a law degree at Hosei University in Tokyo, graduating in 1973.

His first political job was as a political aide to an LDP parliamentarian from Yokohama, Japan’s second-largest city. A decade later, aged 39, he was elected to the Yokohama city council, where he served for nine years, before successfully running in 1996 for the House of Representatives himself. His first ministerial brief came in 2005, when he was chosen as minister for internal affairs and communications by former LDP prime minister Junichiro Koizumi.

Abe had displaced Koizumi as LDP leader and prime minister in 2006 but his ulcerative colitis – combined with growing unpopularity – forced him to step down after only a year. Suga was loyal to Abe in that bleak period and urged him to run for LDP leader again in 2012. He was rewarded with the Cabinet Secretary position when the second Abe government was formed.

It has been a uniquely historically durable political partnership. Abe has been Japan’s longest-serving prime minister, while Suga has been the longest-serving Cabinet Secretary.

Analysts talk of a figure with a special skill for managing Japan’s state bureaucracy. A biography of him is entitled Shadow Power.

Suga’s closeness to Abe suggests he will continue with the outgoing leader’s “Abenomics” reforms, including keeping the Bank of Japan’s foot firmly to the monetary stimulus pedal.

He will also inherit his predecessor’s plans to amend Japan’s pacifist constitution and to legitimise the existence of the country’s self-defence force. Yet given Suga helped steer Abe towards economic reform and away from his nationalist agenda some say it’s unlikely that he will prioritise this.

While Abe was also a “revisionist” about Japan’s brutality in the Second World War, there’s nothing in Suga’s statements that smacks of right-wing nationalist sentiment, though some suspect an inclination to deregulation and free markets (although this is all by Japanese standards).

Suga’s economic inheritance is in some ways even worse than Abe’s. He will have to grapple with the legacy of the Covid-19 crisis, with Japan’s economy projected by the International Monetary Fund to contract by 6 per cent this year as a result of the pandemic.

And the country is still, despite the extraordinary efforts of the past decade, struggling to escape the deflation trap. Productivity growth is feeble, the population is ageing rapidly and the birth rate remains among the lowest of any large developed country.

The geopolitical inheritance is also bleak. America has become an increasingly unreliable military guardian under Donald Trump, while China has been increasingly assertive in the Pacific region.

The next national elections in Japan must take place by autumn 2021. At that point, Suga will have to choose whether to attempt to win a popular mandate on his own terms, or to step aside. If he wants to go down in history as more than a temporary caretaker prime minister he will have to prove himself as a leader over the next year.

Another option is a snap poll later this month, though the hazards of asking people to vote in the midst of a pandemic and its severe economic fallout will be obvious to a seasoned operator like Suga.

Age could be a barrier to success, with Suga six years older than Abe. But reports that he does 200 sit-ups a day and abstains from alcohol suggest reserves of stamina and good health.

Politics is plainly his life, with accounts of his working hours that would make even a Japanese salaryman blush. He and his wife Mariko have three sons but in a recent debate he admitted to having been a largely absentee father.

Useful qualities for an éminence grise perhaps. But can the shadow power handle the limelight?

It remains to be seen whether the man who announced a new Japanese era will play a fundamental role in shaping it.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments