First Russian LGBT+ TV show tells story of gay liberation group’s accidental visit to Soviet Union

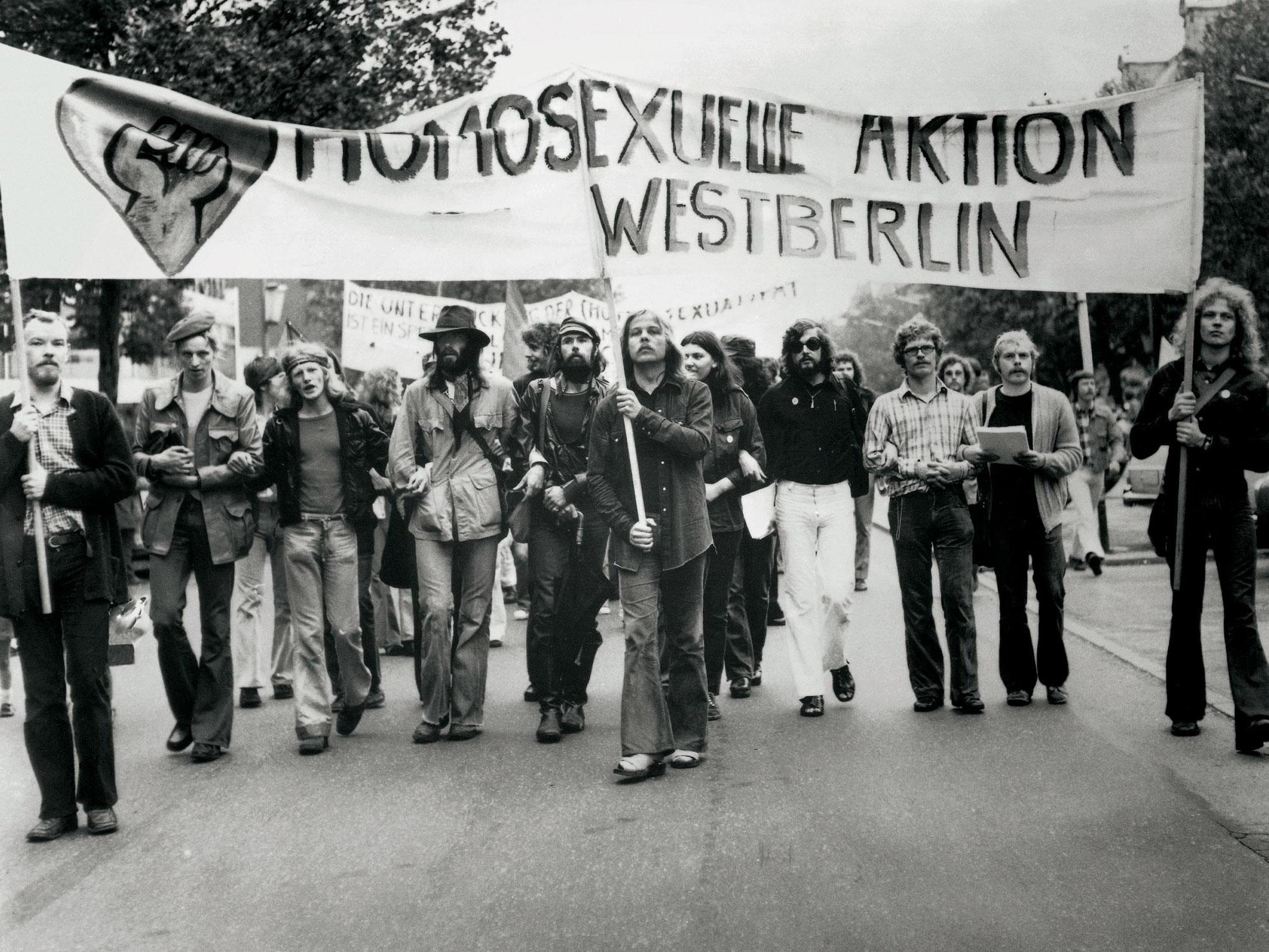

‘Red Rainbow’ takes its cue from the moment the Soviet leadership mistook German gay rights movement for a Communist party faction, as Oliver Carroll reports from Moscow

The year is 1978, and possibly the most unlikely delegation in history has arrived at Moscow’s Sheremetyevo airport as guests of the Soviet Central Committee.

It isn’t hard to recognise the travelling party as they disembark the Lufthansa flight from West Berlin. Two debonair young men are walking down the VIP arrivals corridor, tenderly holding on to each other by intertwined little fingers. A few steps behind them is an older, chubbier female friend with Down’s syndrome, clutching a slobbering English bulldog with comparable affection.

The three left-leaning delegates of Homosexuelle Aktion Westberlin (HAW) have arrived in Moscow with the very best, comradely intentions at heart. But they are also oblivious to the drama that lies in front of them: unaware of the bureaucratic error that saw them mistakenly invited as Soviet guests of honour; and of the gruesome, criminalised reality of LGBT+ life behind the iron curtain.

The tragicomic story of their 10 days in the Soviet Union is the focus of Red Rainbow, the first-ever Russian TV series to explore LGBT+ themes. The show’s producer, Alexander Rodnyansky, who announced the start of the project earlier this month, already has a reputation for prioritising good drama over politics. He co-produced the Golden Globe winner Leviathan, an unflinching portrayal of small-town Russian corruption that was lauded by critics but remains largely unloved in the corridors of power. But while he concedes his latest project will stretch opinions in Russia, he says the country is ready for the test.

“I’ve always believed Russian society is more humane than its laws,” he tells The Independent. “I’m certain the time has come to talk about tolerance using the full range of human emotions. Calmly, authentically, dramatically, sympathetically, but not without irony either.”

Rodnyansky says Red Rainbow will lead with the inherent comedy of the story, employing a light metre generally not seen in Russian television but typical of British dramatic comedies the likes of A Very British Scandal, and Pride. The producer says he has deliberately enlisted an as-yet-unnamed British screenwriter to work on the project. “I can’t say any more since the contract isn’t signed, other than that he is a top-rated writer with several brilliant, funny shows to his name.”

Provided you can push the idea of five-year prison terms to the back of your mind, there’s certainly lots to laugh about. Absurdity rules from the get-go: from the moment Ivan Kapitonov, head of the Soviet executive leadership, travels to West Berlin, and confuses a nascent gay liberation protest for a Communist Party demonstration. Bowled over by the activists’ youthful enthusiasm, Secretary Kapitonov invites them to the Soviet Union. Only much later does a lowly translator in Moscow discover what “HAW” actually stands for.

We sat there in the office laughing, barking HAW-HAW as if we were dogs woofing at each other. Only later did we understand what it meant

Larissa Belzer was 33 and working as a German specialist at the International Institute for the Labour Movement when she got the call to help. The institute was a privileged place to work in the Soviet Union; a crucible of intellectual freedom, where international communists and foreigners and, occasionally, Cambridge spy renegades Don MacClean and Kim Philby mingled. As a result, its library had every western source imaginable. But when Belzer sat down to research a West German communist faction going by the moniker HAW, she was surprised to discover nothing. She took the problem to her manager, who was no wiser.

“We sat there in the office laughing, barking HAW-HAW as if we were dogs woofing at each other,” Belzer says. “We hadn’t a clue. It was only when we made a long-distance call to Germany that we found out Homosexuelle Aktion Westberlin was not, in fact, an obscure Communist youth group.”

The revelation that the Soviet leadership had mistakenly invited a gay emancipation movement had everyone in the institute in stitches. They conjured up all kinds of jokes and dirty poems. “My lonely sweetheart did kick / Three boards with his prick / Every minute, every hour / Grows the Soviet people’s power.” But there was an altogether different reaction when Belzer took her findings to the institute’s curator in the Central Committee. “The poor man put his head in his hands,” she says. “He looked at me and said ‘f**k. What the hell are we going to do?’”

The translator was certain her discovery would put an end to the visit. But the curator said that was impossible. Homosexuality was, after all, a criminal activity, and who knew what might happen to them for passing the scandalous matter further up the chain. So instead a plan was hatched to keep things quiet. Belzer would be asked to look after the VIPs, while naturally keeping up appearances that everything was fine. She would be granted an extra month’s salary, use of an official limousine, and a Central Committee chequebook to cover expenses.

“He told me I could take the delegates anywhere I wanted, ‘shower them with all the queers I could find’ – just as long as they were put on the plane back to Berlin in 10 days’ time,” she recalls.

They asked where the gay diskoteks were. I muttered the nearest were in the prison camps of Siberia

Belzer did her best to hold the line as she travelled back from Sheremetyevo airport with the young German delegation, their older English female friend – she had been brought along as an expression of left-wing solidarity with disabled people – and the bulldog. But the foreigners were living in a different reality. “It was evening and they kept asking when we would arrive in the city because there wasn’t any street lighting back then,” the translator says. ”They were also insistent on finding something called dog food, which I’d never heard of before. Human foodstuffs were not always available in the Soviet Union, you see. And then they asked to see the gay diskoteks.”

At first, Belzer pretended not to understand. The nearest gay diskoteks were in the prison camps of Siberia, she muttered under her breath in Russian, knowing that they would not understand; hopefully the group was not heading there. When they pressed her for an answer, she promised she would accompany them to any club they liked.

Over the next few days, a stand-off ensued. On one side was the translator, doing her best to shield her guests from a terrible reality they knew nothing about. On the other side were the three western activists, still clinging on to idealistic illusions of Soviet freedom, and demanding to be acquainted with the local LGBT+ culture. “They kept insisting I call the gay clubs for them,” Belzer says.

In the end, she resolved to let others do the talking. On the fourth night, she arranged a party at the Moscow State University, enlisting the assistance of former university classmates who spoke English. After filling them in on the unusual nature of the delegation, she left everyone to their own devices. The breakthrough happened sometime that evening. “The next day they pinned me to a wall and demanded answers,” she says.

Finding a place to talk was not easy. Belzer understood the KGB was following the delegation at every step. She knew their gestures from years of accompanying foreign groups; the “glare of the agents’ eyes” and the “faces that reminded you of stuffed animals”. She knew how they would always find a way of sitting at the table next to the group – even if it was already occupied. But she also remembered there was a chocolatier cafe near to Gorky Park, which had one isolated corner table away from the rest. So that was where she took the group to finally come clean.

“We talked and we talked and we talked in that cafe,” Belzer remembers, “and by the end, those pretty boys were crying.” She told them about the criminal code and the five-year prison sentences. She told them about the persecution and how all was not how it seemed when it came to Soviet freedom. She told them about how it was just a big mistake that they were invited here. They had their own questions: was the official who came to see them each morning at breakfast as gay-friendly as he said he was, or was he also KGB? “I said the fact they were sipping hot chocolate in a nice cafe in Moscow, and not in a Siberian prison, meant he was gay-friendly, or at least to some degree.”

Being gay was seen as a terrible crime back then, and people would persecute it in such a condescending way

By now, the translator was beginning to feel a connection with her guests. She decided she would do what she could to help them make contact with like-minded Soviets. But it was not easy. She certainly knew gay people – she was friends with many artists – but neither she nor they were willing to risk their lives to talk about it openly. But then the translator remembered that lesbians would often scribble telephone numbers and offers for sex on the walls of public toilets; perhaps, she said, gay men did too. “Their faces lit up,” Belzer says. “They squealed and said they wanted to go to the toilets.”

The next day, Belzer and her husband took the delegation to the one set of clean public conveniences they knew, across from present-day Kitai-gorod metro station in downtown Moscow. They weren’t far from the Kremlin, so police officers were everywhere. But once they saw the coast was clear, the group separated into their respective sexes, descended to the privies, and took out their cameras. “We saw nothing in the ladies, but it was clear the boys struck gold, and we could hear them guffawing, and whooping with glee. We had to drag them out of there in the end. I nearly went grey from the fear of being busted by the police.”

Producer Rodnyansky, who realised he had struck his own dramatic gold when he heard the story, says he remembers seeing the graffiti and sexual offers that gay men would scribble on the walls back in those days. “It must have been truly dreadful for these people back then, so difficult, so awful,” he says. Some of his friends were imprisoned for their sexual orientation, he adds, including the renowned film director of the Soviet sixties, Sergei Parajanov. “Being gay was seen as a terrible crime in the 1970s, and people would persecute it in such a condescending way.”

The televised version of the West German visit has no obvious happy ending to draw on. There isn’t the feel-good conclusion of Pride, no alliance between LGBT+ communities and trade unions, politicians or the labour movement. Instead, at the end of the 10 days, the activists of Homosexuelle Aktion Westberlin were simply sent back to Germany. It would be another 15 years, and plenty more hurt and persecution, before homosexuality was eventually decriminalised. In some ways, of course, the political culture of Russian has barely moved on to this day.

But the funny and tragic events that accompanied the most unlikely of foreign delegations left a profound impact on the Soviet hosts.

“It was the harshest of learning curves,” says Belzer. “Every day we came across something new that demanded a revision of our basic understandings. The trip changed their world, but it turned my world upside down too.”

Belzer, who would go on to teach gender studies as an emigre professor of the Free University in Berlin, says she often thinks about what became of the two men and their friend.

“Invariably, I’m transported back to the moments after we said goodbye, the journey from the airport in the back of that idiotic limousine. Then and now the tears are flowing – a protest at the cognitive dissonance it required to stay human.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments