How 3.6 million Indian ‘citizens’ had some of their rights removed overnight

Overseas Citizens of India share with Namita Singh their concerns about recent changes to rules surrounding permanent residency permits offered to foreign nationals of Indian origin

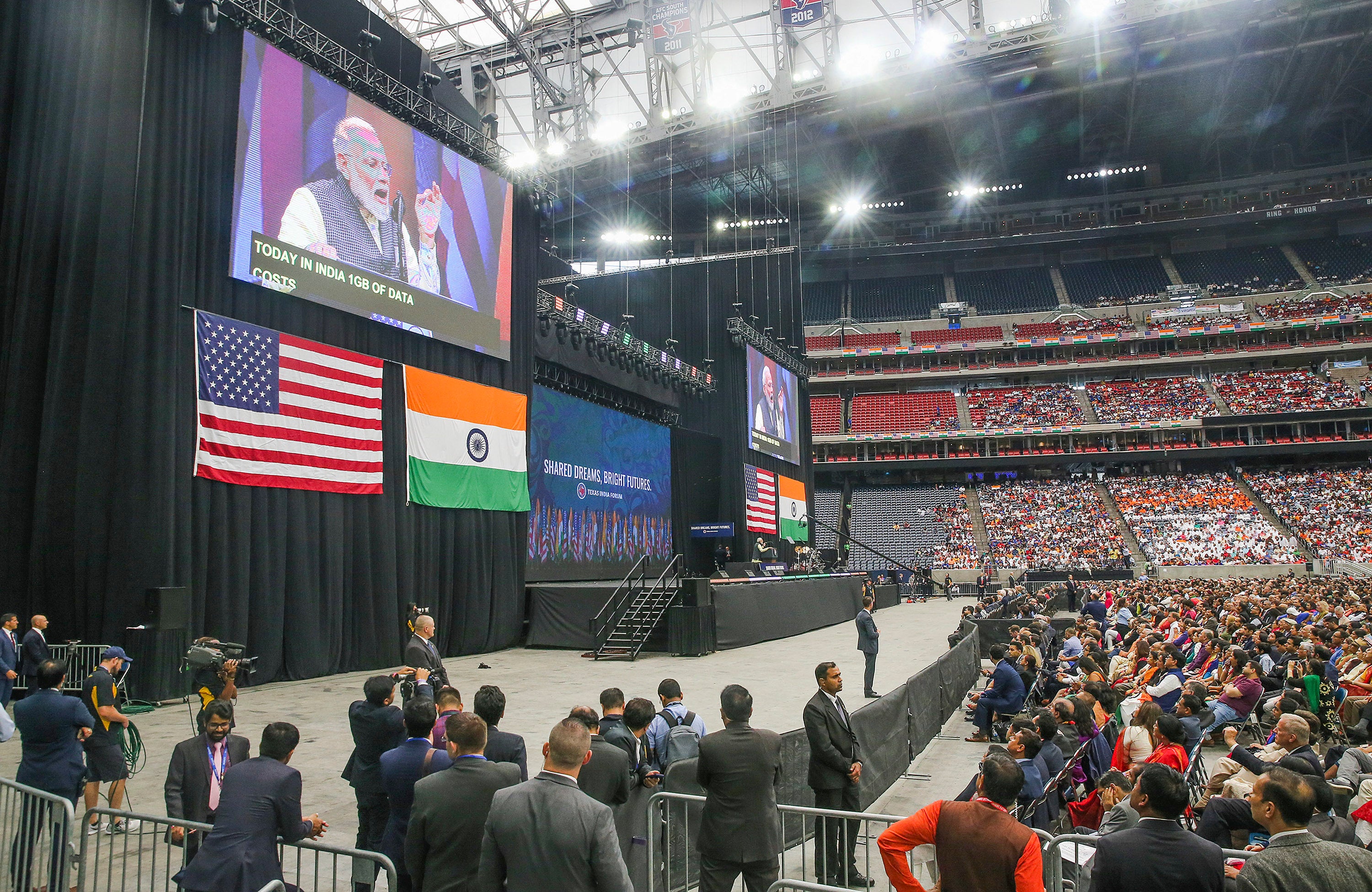

When Narendra Modi addressed a gathering of his country’s diaspora in the Netherlands in 2017, he urged them all to sign up for a document that would give them almost all the same rights as a full Indian citizen, in recognition of their heritage and ties to the motherland.

The Overseas Citizenship of India (OCI) card, he told them, “is your age-old link with India”. “This knot should not be opened or weighed against money and currency,” he said. “People who live here may have a different coloured passport but a different passport cannot change blood relations.”

First introduced in 2005, the card was seen as plugging the gap of dual citizenship – which India does not allow. It functions a lot like an American Green Card or the permanent residence card in the UK, giving members of the Indian diaspora all the same rights as an Indian national except for owning agricultural land, voting and getting a government job.

That all changed last month, however, when without consultation the government issued a legal “notification” restricting the rights of an estimated 3.6 million OCI card-holders for the first time.

The new rules seek to extend the Modi administration’s control OCI card-holders’ ability to engage in certain activities deemed controversial. It prevents them from engaging in any “Missionary or Tablighi” work – Tablighi Jamaat is a major international body of Islamic missionaries.

It also bars them from “journalistic activities” or “research” unless they apply for and receive express permission from a government agency that oversees the activities of foreigners in the country, and where normal visa holders must register.

And it will also make it harder for them to gain places to study for higher education in India, requiring them to apply for seats reserved for non-resident Indians (NRIs) rather than in the general category.

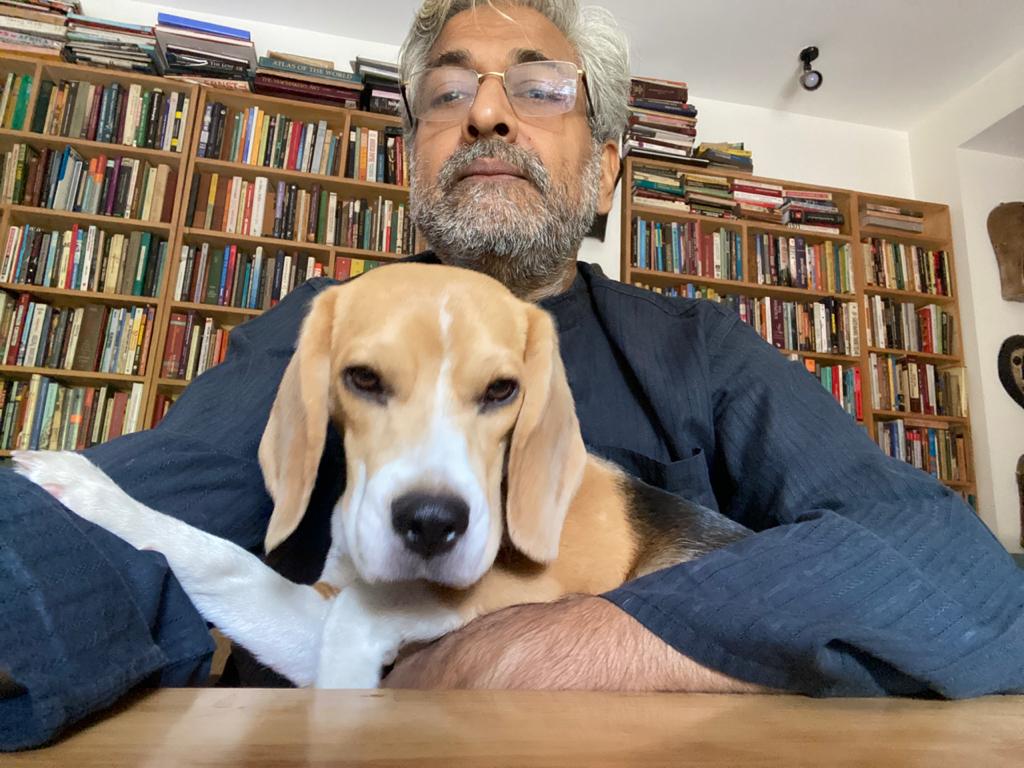

Siddharth Varadarajan, 55, an Indian-American journalist and founding editor of online news portal The Wire, says there has been no clarity over how people like him might be affected since the changes were issued on 4 March.

“There are hundreds and likely thousands of OCIs who are living and working in India for Indian companies and universities whose status has been rendered ambiguous,” he tells The Independent. “OCIs have been told, for example, that government permission is needed to conduct ‘research’. But what constitutes ‘research’ is undefined.”

Many OCI card-holders are unlikely to be directly affected by the new rules, but the manner in which they were abruptly changed has left them uneasy.

Shashank, 30, is a British national of Indian origin who applied for Overseas Citizenship of India (OCI) card about a decade ago when he moved to the UK to study at university. “Because my parents, my family, everyone is back in India, the OCI card gives me the right to visit them. It also gives me the right to pursue any sort of business activity in the future,” he says.

He says the new restrictions make him anxious “about what further the government can do in that regard”. “What bothers me is the rights that are taken away... these were granted to OCIs.”

Naren Thappeta, a 56-year-old US citizen and OCI card-holder, sees the move as a nationalist step in the wrong direction that does not recognise that “life is right now a lot more dynamic” and with virtual connectivity, borders are becoming increasingly less relevant to normal people’s lives. “The government will take a very moralistic position. It will ask: ‘If you are so serious about India’s citizenship, then why don’t you give up your foreign citizenship?’,” he says.

“But the point is, for knowledge workers like me borders are immaterial. I am 56 and I have lived in India for the last 21 years. For the next five to 10 years, I might want to move to the US to stay closer to my daughters. And for the following five to 10 years, I might return to India to stay closer to my parents.”

When approached by The Independent with a detailed set of questions on the OCI changes, the Indian home ministry did not respond by the time of publication.

But not everyone – even among OCI card-holders – disagrees with the government decision. “You have to agree that people who have chosen to take citizenship outside [India], even though they knew they would lose their Indian citizenship, have done that [with] a conscious mind,” says Abhishek Gupta, a 32-year-old Australian national and an OCI card-holder. “It is not like the government is being unfair or anything.”

Inevitably there are those who will see the move as just the latest by Modi’s ruling BJP party to crack down on dissenting voices. It has already targeted organisations that do research into human rights issues, most notably freezing Amnesty International’s accounts in September last year.

While the government said the NGO had broken the law by circumventing rules around foreign donations, the move came shortly after Amnesty India released reports criticising the government for its record in Kashmir and the authorities’ role in the deadly Delhi riots of February 2020.

Varadarajan says the move is about sending out a message, and reflects what he calls the government’s “paranoia”. “Modi was happy to cultivate OCIs as long as he was confident of their political support,” he says. “But with OCIs echoing some of the dissatisfaction towards government policies that many Indians in India feel, the BJP wishes to send a message that there may be a cost to pay – the rights which come with OCI status can easily be taken away.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments