‘They are choking us’: In Kashmir, government employees fear new rule that scan their social media

‘As Kashmiris, we always know that anything we post online can land us in trouble’. By Stuti Mishra

As the long internet blackout in Kashmir finally began to lift, many young people in Kashmir found a renewed sense of hope. For one 23-year-old history graduate, the return of 4G services at his Srinagar home, was a chance to finally begin preparing for one of India’s most prestigious exams.

It would not only launch his dream career, he hoped, but also provide him a ticket out of the troubled state, which, situated at the heart of the India-Pakistan conflict, has been witnessing decades of turmoil. But a new state directive that requires the social media history of government employees to be scanned for objectionable activity has become a major bone of contention for thousands like him in the region.

Born and raised in one of the world’s most militarised zones, plagued by frequent internet blackouts, Majid is no stranger to the nanny state watching every move of Kashmiris.

The new directive is being seen as yet another example of government overreach and censoring of free speech in the already troubled region.

“As Kashmiris, we always know that anything we post online can land us in trouble,” said the history graduate, who works part-time as he prepares for a federal civil services exam. “I don’t post anything controversial or political, but I am worried.”

Last month, Jammu and Kashmir’s General Administration Department (GAD) released an order that requires every new government employee in the state to go through a verification process which will include a thorough scan of their social media activity. Needless to say, extreme opinions or harsh criticism of the government would invite censure.

The 3 March order also states that employees who don’t get this verification process done by the Criminal Investigation Department (CID) will not be paid a salary or allowance until they comply.

“Many individuals with dubious character antecedents and conduct have been paid salaries and other allowances, without obtaining their mandatory CID verification,” the GAD circular said, adding that the verification of such cases should be “completed expeditiously.”

The issue of perceived radicalisation in the federal territory’s employee ranks is not new. Employees in J&K already have to go through a three-stage verification process after getting an appointment letter. It includes a background check by the local police, the CID, and police counterintelligence, which is more than what is required of candidates in any other state in India.

However, for people like the history graduate, one of Kashmir’s tens of thousands of youngsters who see government work as means to have a decent life, this new rule has managed to instil a sense of fear and rekindled further suspicion of the Indian state.

One teacher at a government school in Srinagar, who also did not want to give his name, labels the new circular an attempt to “suffocate” Kashmiris. He said it has made him and his colleagues rethink their social media use.

“If you live in Kashmir, politics and human rights issues are all you see and hear about in a day,” the 28-year-old high-school teacher said. “But if you can’t speak about it, then what is the point of being on social media?”

“By not letting us speak up for ourselves and what we see around, they are choking us,” he said.

The teacher said his department hasn’t officially informed him or his colleagues about the new rules and haven’t asked for information about their social media profiles, but the news of the directive has reinforced a sense of siege in them.

The day after the news of the directive, he said, it was “all anyone could talk about.”

He said he has already witnessed several of his friends being harassed under various laws for posting something even mildly critical of the government or of India’s role in Kashmir, which makes him worry about the repercussions about the directive all the more.

“As someone who works and knows this area, I can have opinions on policies too, I might have a good suggestion to improve things, I also want peace,” he said. “But with laws like these, it feels it is pointless to be on social media.”

Another ardent Twitter user, who wished to remain anonymous, joined a junior-level job at a government department last year. He said he is filled with regret on using social media for sharing opinions as fear mounts.

“I never revealed my identity while tweeting,” the 25-year-old software engineer said. “But it gave me a chance to be a part of a vocal community of Kashmiris who don’t want to suffer silently but want to share what is our reality.”

“I don’t think I have posted anything illegal or wrong,” he said. He, however, expressed worry over his posts during the repeal of Article 370. The lives of residents of Kashmir valley took a turn for the worse in 2019 when the government of Hindu nationalist Narendra Modi stripped the region of its previous autonomy.

What followed was a long and harsh crackdown on residents, with enforced blackout of internet and cellular services, an increase in deployment of Indian troops and the use of a controversial detention law to place regional state leaders and top politicians under house arrest.

The government hasn’t clarified how the order will be implemented, or if there’s a timeline within which these verifications have to be conducted. Manoj Dwivedi, the principle secretary for the general administration department for Kashmir, who signed the order, has not responded to a request for comment.

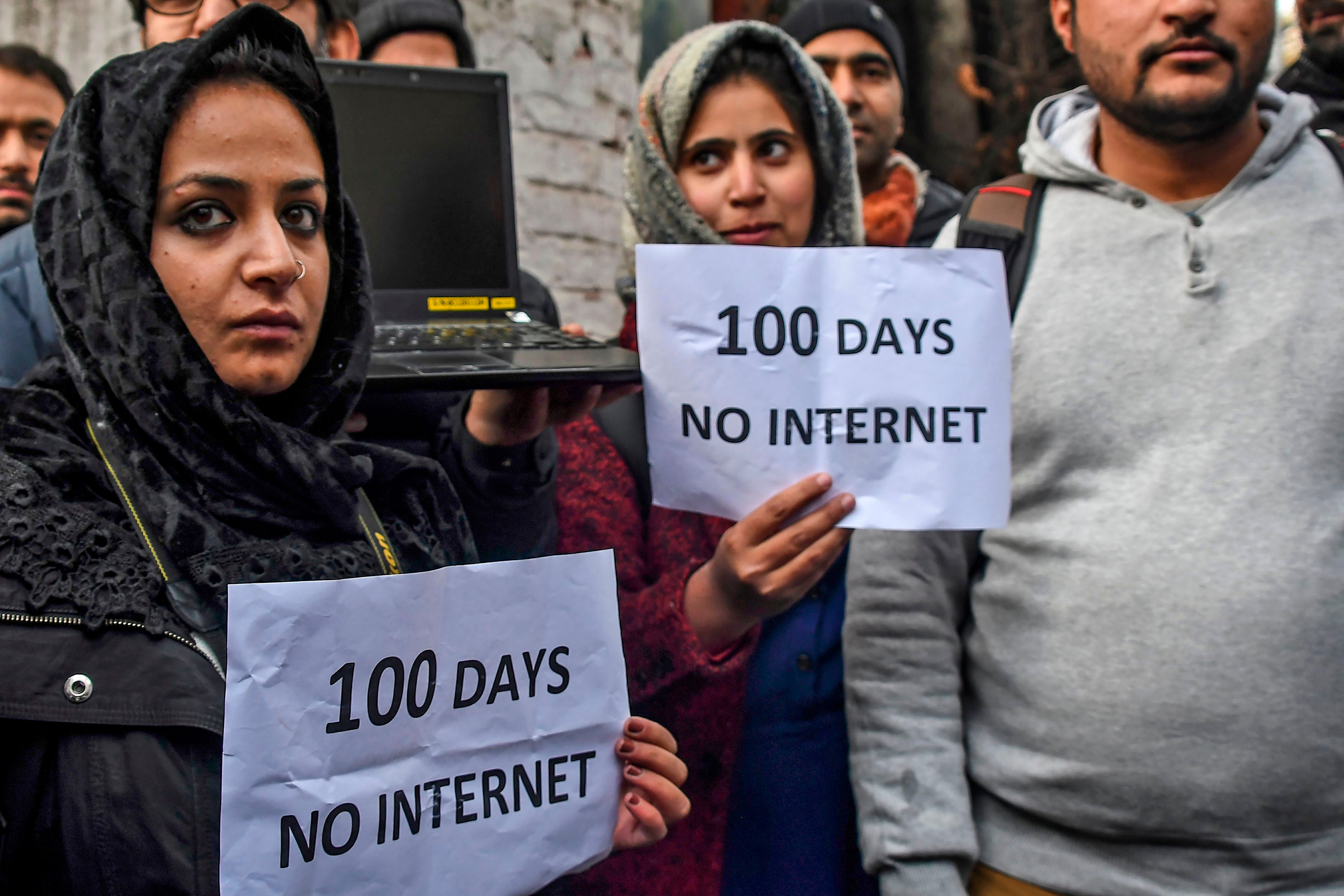

The recent internet shutdown in Kashmir was one of the longest ever reported in a democratic country.

The government allowed 2G internet (250kbps) in the region after five months in January 2020, a speed which does not allow full functionality for most web sites and web-based applications. It hampered studies for thousands of students and curbed the free speech of residents cut off from the world, especially during a raging pandemic in which access to online information was essential.

After almost two years, in February 2021, 4G internet services were restored in all districts of Jammu and Kashmir.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments