World’s biggest vaccine drive slowed down by lack of trust in India’s homegrown coronavirus jab

While burnishing its international image as a vaccine powerhouse, India’s domestic inoculation drive has struggled to convince its own people that a homegrown jab is safe, as Shweta Sharma reports

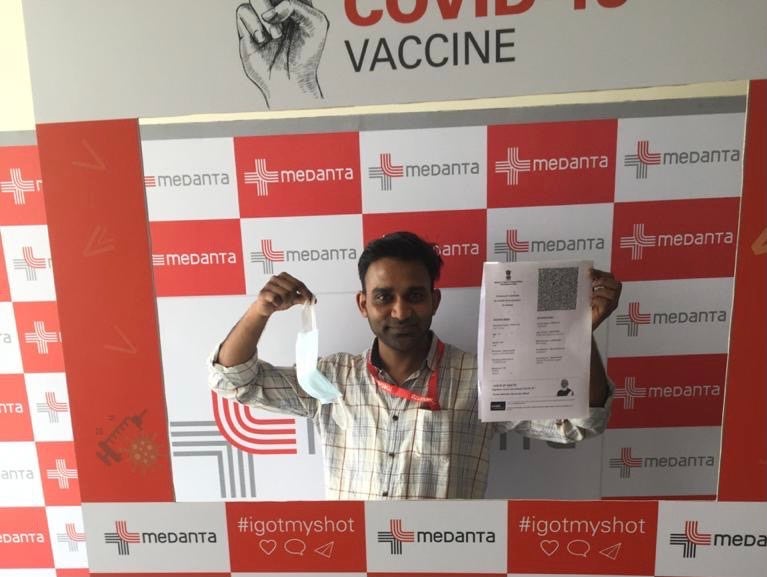

Frontline healthcare worker Vipin Thomas has spent the past year serving at a Covid-19 hospital in India’s burgeoning industrial town of Gurugram. When he heard that he had to have the coronavirus shot, he had only one question: which one?

India, home to the world’s largest vaccine-maker Serum Institute of India (SII) and acknowledged as the “pharmacy of the world”, has invested considerable effort into establishing vaccine diplomacy with its Asian neighbours. However, at home, it’s struggling with a unique problem: vaccine hesitancy spreading through word-of-mouth about the efficacy of its homegrown coronavirus shot, Covaxin.

“I have managed to stay safe from Covid-19 all these months even while working at the hospital, why would I take something that’s results are unknown?” Thomas told The Independent the day he got his second jab of Covishield, the brand name in India for the vaccine developed by AstraZeneca and the University of Oxford.

Thomas shares his scepticism with millions of others spooked by the initial public communication around Covaxin’s lack of late-stage clinical trial data.

It all started with Indian regulators clearing Covaxin, developed by India’s own Bharat Biotech, to be used on millions even before it had completed crucial final stage trials. One other vaccine candidate, the Oxford-AstraZeneca jab, was also cleared for use.

Covaxin’s data from late-stage trials only came in March, finding it to be 80 per cent efficacious. By then it had already been injected into thousands of people and shipped to other countries.

India kickstarted the world’s largest immunisation drive on 16 January with a target to inoculate 300 million people by August, even as doubts swirled around Covaxin.

More than 50 days after the drive began, receptiveness of the two vaccines could be seen in the numbers. According to official data, just about 8 per cent of the people vaccinated across India received Covaxin while approximately 91 per cent had the Oxford-AstraZeneca jab.

Since January, India has administered at least one vaccine dose to a total of 26 million people. Out of the total, however, only 47,000 have been fully vaccinated with two doses.

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi took the Covaxin shot on 1 March, kicking-off the second phase of the drive, in a possible attempt to lead by example for those suspicious of the jab as questions mounted over his participation in the drive.

Top politicians, including Foreign Minister S Jaishankar, President Ram Nath Kovind and Health Minister Harsh Vardhan followed the prime minister’s example in taking the Indian-made vaccine to instil confidence in people. However, experts say the damage was already done with “mixed signals” from the government and pitfalls in messaging.

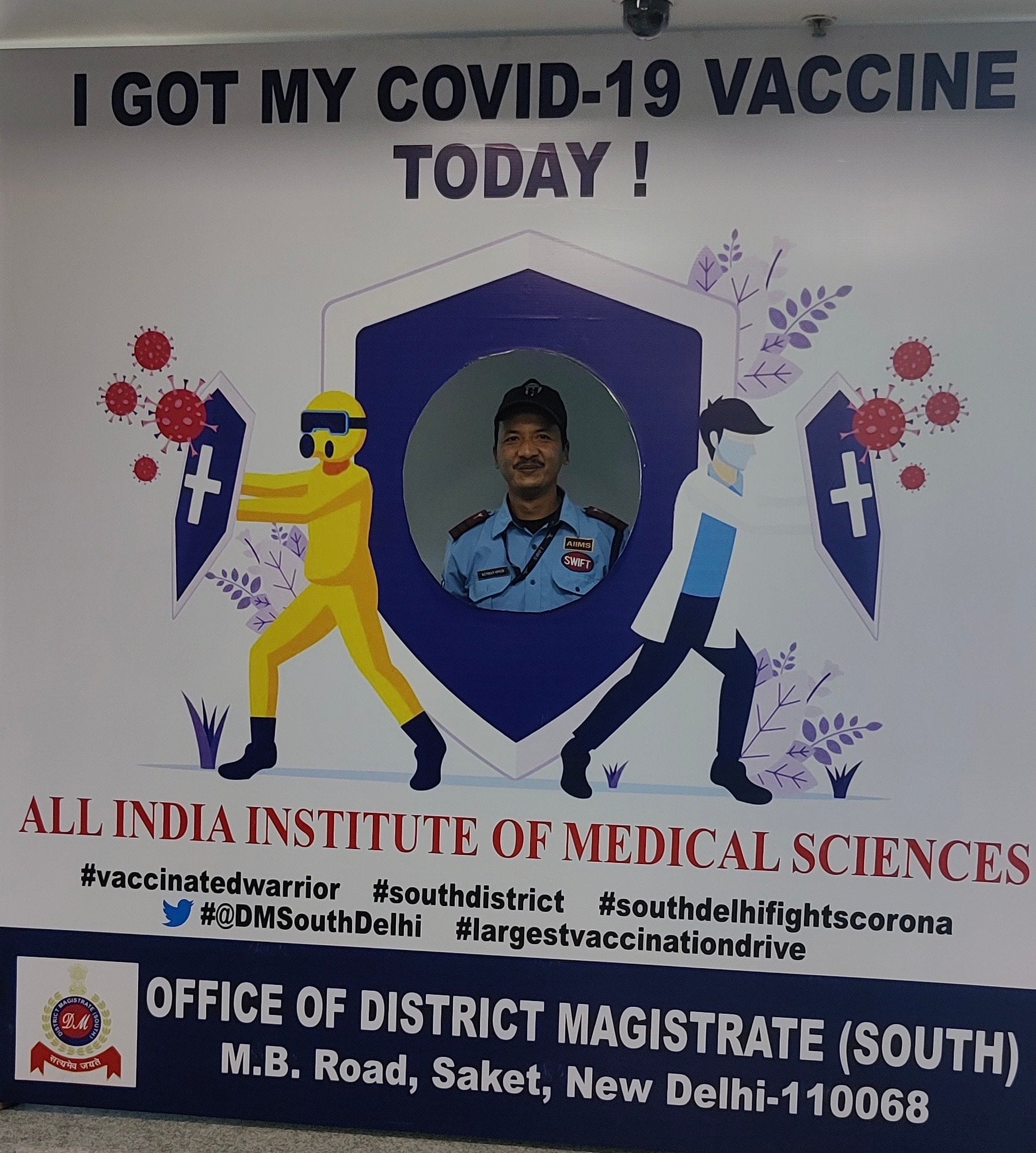

Srinivas Rajkumar, former general secretary at India’s premier All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS) in Delhi, said experts cannot point to any one single problem that has set India’s vaccination drive back. Countries such as India, with its huge population, are bound to have initial hiccups, he said.

“Poor messaging can be said to be the reason for distrust in the Indian vaccine but vaccine hesitancy has been a global phenomenon. Lack of data regarding the efficacy of vaccine was an issue worldwide, but more so with India, because we did not have data for Covaxin,” he said.

The health ministry itself promoted alternate medicines such as Coronil – an ayurvedic medicine touted as a cure for coronavirus by its makers – and later urged people to trust a synthetic vaccine. This kind of mixed messaging has tainted the image of vaccines, Rajkumar added.

Oommen John, a public health expert from Bengaluru, who has worked with the World Health Organisation (WHO) on vaccine development, said vaccine hesitancy can only be overcome by way of transparency of information and that there would have been more confidence had the trial data for Covaxin been published.

“There has been a significant amount of vaccine hesitancy also because health workers are an aware lot. And when there is so much sensitivity or sensitisation around evidence than some level of concrete evidence being available would definitely boost vaccine uptick,” Dr John said.

India’s vaccination programme had fallen flat a few weeks after it was rolled out, with only half the targeted numbers turning up for the shots. Many did not turn up at the vaccine centres amid fears of side effects, doubts, and the conspicuous absence of politicians themselves taking the vaccines.

Despite the initial sluggish response, India has not only vaccinated more than 26 million people but also opened the process up to the private sector, allowing it to catch up with countries such as the US and UK which started much earlier.

Currently, the country is behind its overall 300 million target, averaging 1.1 million vaccine doses per day while it needs to maintain a daily average of 1.6 million.

Several frontline workers prefer not to get vaccinated till they know what the side effects are.

“I am afraid of the complications and uncertain about its results right now. There has been word of mouth among people to not get vaccinated as no one can force us,” said Abuzar Saifi, a frontline worker in Delhi. Saifi said he based his opinion on stories he heard about people dying after getting the coronavirus shots.

J Radhakrishnan Jagannath, health secretary of the southern Tamil Nadu state, said the “drive started slow in the state with frontline workers” but the response from elderly and comorbid people in second phase of the drive has been “heartening”.

Though it was too soon to say whether the trend would continue, he said.

“Earlier we used to average around 12,000 to 15,000 vaccinations in a day. But on the first day of the second phase we vaccinated 23,000 odd cases and in the second day around 41,000 cases,” he said.

“In bigger cities, people are trying to identify sites of Covaxin and Covishield. But more jabs of Oxford’s vaccine have been given due to its [greater] availability than Covaxin,” he added.

India is the fourth country in the world in terms of the total number of vaccine doses administered, though its huge population means it is averaging only 1.9 doses per 100 people. That compares to the UK administering more than 36 doses per 100 people or the 29. Israel is the only country in the world to have passed 100 doses administered per 100 people.

Medical journal The Lancet declared in March that the second phase trial of Covaxin showed it to be “safe and immunogenic” but added that its efficacy cannot be determined without data from the third phase.

While India wades through these challenges at home, it has shipped about 57 million of doses to foreign countries. SK Sarin, director of the Institute of Liver and Biliary Sciences, praised the rollout as “well organised” but said there’s scope to do better.

“We should certainly speed up,” said Dr Sarin, who headed the Delhi government’s first committee on managing Covid-19 infections.

“That being said, I think India may be the only or may be one of the few countries to have vaccine surplus as of now. Hence, the only thing we require is the enrolment of the people to get vaccinated.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments