Should we stay, or should we go? Hong Kong residents grapple with life in a changed city

The one year anniversary of Hong Kong’s national security law is approaching, and in 12 months it has already changed the city, reports William Yang

Gavin Mok never expected that the time for him and his family to leave Hong Kong would come so soon, but last July, the situation in his hometown deteriorated so quickly he could no longer find a reason to stay.

Almost a year ago, the Chinese government passed its national security law (NSL), which makes it easier to punish protesters and also reduces the city’s autonomy. Penalties have been increased – up to life imprisonment for “crimes of subversion” – and some serious cases can now be tried in mainland China.

Critics say the legislation curtails democratic freedoms, whereas China views it as reintroducing stability.

“Unlike most Hong Kong people, my family have been planning [to emigrate] since 2015, as I saw signs that suggested the Chinese government was trying to increase their control over Hong Kong,” says Mr Mok. “Originally I thought we would leave the city in 2025, but following the imposition of the NSL last July, I realised there is no more reason to stay in Hong Kong.”

Mr Mok, 42, used to work as a stock trader in Hong Kong. He and his wife and two daughters moved to the UK in October 2020, after the British government unveiled the new immigration scheme for Hong Kong people who hold British national overseas (BNO) status.

Mr Mok sold his house in Hong Kong two years ago, which gave him more flexibility as to the timing of his departure. Others haven’t been so fortunate.

According to a report published in May by the Migration Observatory at the University of Oxford, 34,000 Hong Kong residents have applied to live in the UK in the first three months of 2021.

The story of Mr Mok and his family represents a growing trend in Hong Kong, as those living in the former British colony feel increasingly threatened by the controversial law and a wide range of other measures that the Hong Kong and Chinese governments have used to detain and prosecute prominent activists as well as normal citizens.

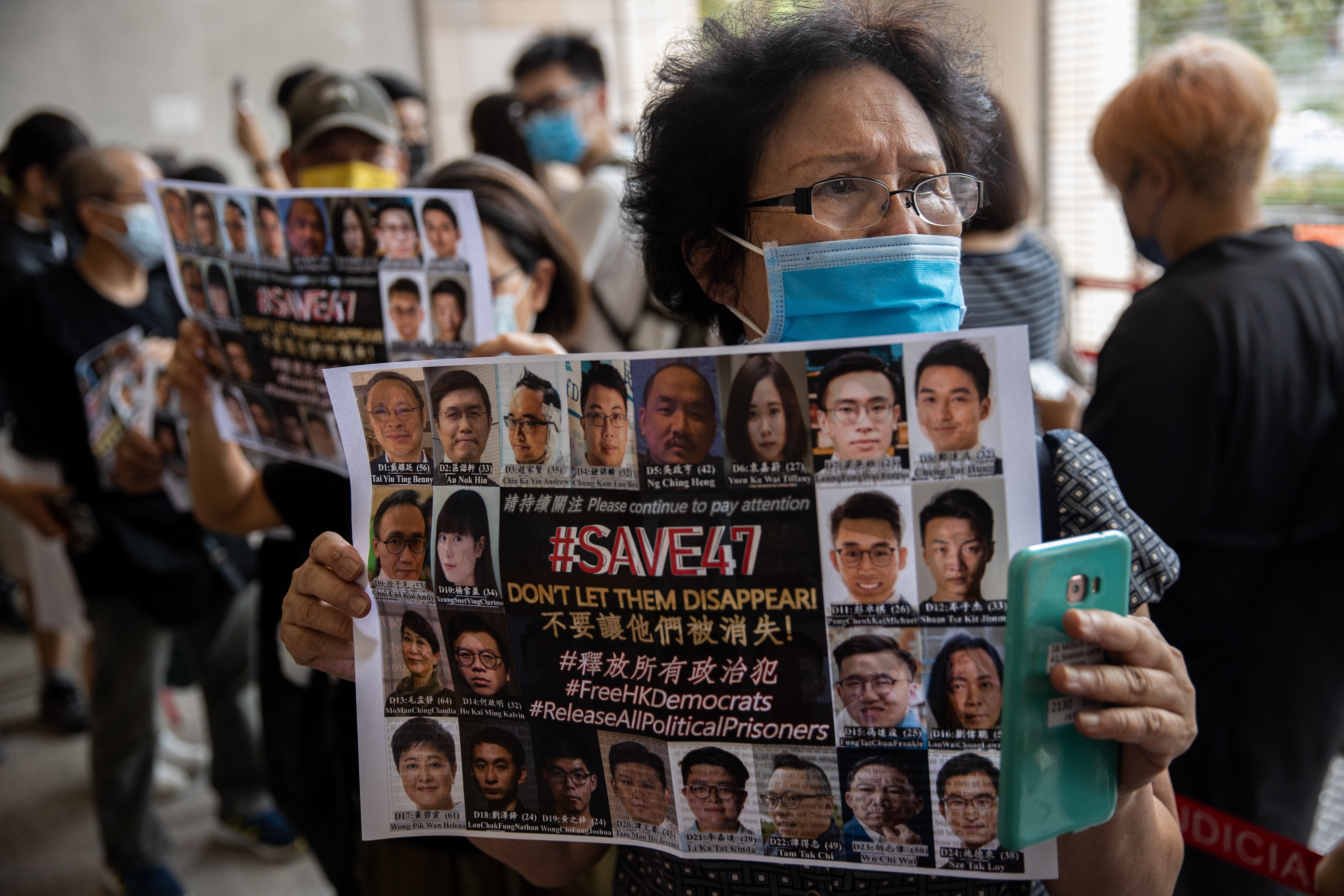

According to data collected by the Georgetown Centre for Asian Law last month, the National Security Department (NSD) within the Hong Kong Police has made 113 arrests, including those of 92 individuals who were detained for allegedly violating the NSL, since last July.

After reviewing all the cases brought under the NSL, Georgetown’s Lydia Wong and Thomas Kellogg concluded that the law has been used to “punish the exercise of basic political rights by the government’s peaceful critics”.

In the eyes of some Hong Kong residents who are still in the city, the NSL has blurred the lines when it comes to what they can say and what they can do.

“The boundary keeps moving and the government has been very harsh when it comes to suppressing the pro-democracy movement in Hong Kong,” says Tim Leung, a business owner in Hong Kong who plans to move to the UK in two years’ time.

Mr Leung thinks the choice facing Hong Kong people now is much starker compared with that faced by emigrants in the 1980s and 1990s. “When they chose to move to western countries, they knew there was still a place that they could call home and that they could always visit Hong Kong,” he says.

“If the situation in Hong Kong continues to deteriorate, I would feel like I shouldn’t come back to visit after I move to the UK. I think the Hong Kong government and Chinese government are trying to destroy the norms that Hong Kong’s civil society has established over the last few decades,” he adds.

A division of work

Alongside arrests made under the NSL, the Hong Kong police has increased the frequency of those made under other laws, targeting prominent pro-democracy figures including activist and politician Joshua Wong, media mogul Jimmy Lai, and other former legislators.

Chow Hang Tung, a Hong Kong barrister and vice chair of the Hong Kong Alliance, became the latest target of Beijing’s most recent crackdown. She was arrested last Friday for allegedly using social media to publicise an unauthorised assembly – the annual Tiananmen Vigil, commemorating the 1989 pro-democracy crackdown, which has been banned by the police for the second year in a row.

After she was released on Saturday, Chow characterised the arrest as the government trying to “frighten” people and prevent them from marking the anniversary of the Tiananmen Square crackdown. To her, the imposition of the NSL has made it more difficult to work and plan events because simple actions that no one used to care about will need to be debated over and over again.

“It’s been much more difficult to coordinate actions and make people come out,” explains Chow. “The law has damaged the social fabric that used to bring different parties in Hong Kong’s civil society together.”

Despite the worsening conditions for civil society groups like the Hong Kong Alliance, Chow says she has no plans to leave the city. She believes that activists like her can achieve more by staying in Hong Kong. “I think if you want people to continue the fight, you first have to be there and not abandon them,” she says.

Previously, we always thought about Hong Kong as a physical place, but we now need to highlight the core values including democracy, freedom and social justice that define Hong Kongers

“You should explore and expand every space and action that still exists. I think there are a lot of lessons from other campaigns and other people’s movements,” she adds.

She cites the Tiananmen Square pro-democracy protests as an example. Following the bloody crackdown in Beijing in 1989, several key student leaders were forced into exile while some activists remained in China to fight for the cause of the movement. “Those who are outside of China are supporting what’s happening in China, and that’s how it should be,” Chow says of the movement today.

“I’m not saying it’s not important to have people abroad to do international lobbying, as it’s a sacrifice to leave Hong Kong. While someone needs to do that, someone also needs to stay in Hong Kong. It’s a division of work,” she explains.

For Hong Kong residents who have moved to the UK, one of the important missions now is to find ways to uphold the core values that define Hong Kong as it used to be.

“Previously, we always thought about Hong Kong as a physical place, but we now need to highlight the core values, including democracy, freedom and social justice, that define Hong Kongers,” says Simon Cheng, a former staffer at the British consulate in Hong Kong, who now lives in London.

Gavin Mok agrees with Mr Cheng’s ideas.

While he may have felt compelled to leave the city itself, he hasn’t given up on his former home.

“I can keep upholding the spirit and values of Hong Kong no matter where I am, but it no longer makes sense for me to remain in Hong Kong,” he says.

“Leaving the city behind doesn’t mean I don’t love Hong Kong, but I need to give up on some things that I can no longer reclaim.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments