Hong Kong’s outgoing leader Carrie Lam leaves behind a lame duck legacy as China cements its control

Lam once declared she must serve two masters – Beijing and the people of Hong Kong – but critics say her tenure reflects how she bowed to China at the expense of the city’s civil liberties, writes William Yang

When Carrie Lam became Hong Kong’s chief executive in 2017, she vowed to “rebuild a harmonious society”, “restore confidence” in the state, and ensure that implementation of its policies “be more closely aligned with public opinion”.

However, following a turbulent five-year tenure that has been marked by a months-long protest against the government, Beijing’s crackdown on civil society after the implementation of the national security law, and an exodus of tens of thousands of Hong Kongers from the city, Lam announced last week that she will leave office in June when her term ends.

In a spell defined by ever-increasing Chinese control over the semi-autonomous city, Lam is likely to go down as the region’s most divisive leader.

While the most recent opinion poll from the Hong Kong Public Opinion Research Institute showed that Lam’s approval rating was at 26.6 per cent in March, it stood at just 18 per cent in February 2020, the lowest among any Hong Kong chief executive.

Some analysts said they already saw signs that Lam would be a leader who would be prepared to adopt heavy-handed measures to rule back in 2017.

“When Lam was secretary for one policy bureau in Hong Kong, she already showed a hardline approach that undermined public consultation and dialogue,” says Eric Lai, a Hong Kong law fellow at Georgetown University’s Center for Asian Law.

Following one of the biggest marches during the 2019 anti-extradition bill movement, Hong Kong political commentator Alice Wu described Lam as “arrogant”.

“Lam’s arrogance is epic and has made her tone-deaf, blind and stubborn, so much so that she has managed to outdo her predecessors Tung Chee-hwa and Leung Chun-ying in creating social rift and pushing public anger over the point of no return in record time,” Wu wrote in a 2019 article.

Lai saysthat while the main task for the local administration in Hong Kong is to execute the Chinese government’s instruction to crack down on political opposition, the main problem withLam’s administration is her hostility towards public consultations and engagement with different stakeholders.

“As you can see how she and her colleagues handled the extradition amendment, it could be handled smoothly with better consultation with stakeholders and to listen to the recommendations made by legal professionals and business groups,” he tells The Independent. “She refused and she disregarded all the potential consequences and that led to the outbreak of the movement.”

“There is a strong imperative from Beijing to eliminate political opposition in Hong Kong but Carrie Lam’s administration, including her style and her approach, had only added fuel to the political initiatives from Beijing,” he adds.

However, some of Lam’s political advisers defended her style of governance and described her as the “most misunderstood” chief executive since Hong Kong’s handover from the UK to China in 1997.

“The opposition is not very fond of her following the ‘riot’ in 2019, and towards the end of her first term, different factions in the pro-government camp begin to vie for positions to try to run for the next chief executive,” says Ronny Tong, a member of the cabinet that advises Lam.

“Obviously, they wouldn’t be there to defend the chief executive. Rather, even the pro-government parties were trying to upstage her so as to fortify their respective positions if they have a chance to run for chief executive,” he adds.

Tong adds that criticisms of Lam as being stubborn or arrogant are unfair.

“I think people need to understand that the chief executive is the chief executive of the entire Hong Kong. She is answerable to the entire population. When there are difficult decisions to make, obviously she has to listen to all interested parties.”

However, other experts believe Lam’s decision to introduce amendments to Hong Kong’s extradition bill and the handling of the months-long protest – which was often characterised by violent clashes between protesters and police– set the stage for the Chinese government to bypass the city’s existing institutions and impose the controversial national security law (NSL).

“While Lam was not the one who pushed for the NSL, her actions in 2019 created the conditions for Beijing to feel the need for such a thing,” says Lev Nachman, a postdoctoral research fellow at the Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies at Harvard University.

“What makes Lam’s tenure particularly important is that she is the chief executive that served in the transition of pre-NSL and post-NSL Hong Kong. She was the one who bridged the two eras.”

Since the implementation of the controversial law, hundreds of activists, opposition figures and students have been arrested and detained while several pro-democracy media outlets and dozens of civil society organisations have also been forced to shut down as authorities ramped up their crackdown on civil society.

And as the pre-trial proceedings drag on for some high-profile cases under the NSL, observers are concerned that the government has become more willing to weaponise different legal tools to target dissenting voices in the city, and fear it could have damaging consequences for judicial independence and rule of law in Hong Kong.

“The erosion of judicial independence and the rule of law is mainly sourced from Beijing’s interference to Hong Kong by imposing the NSL and by interpreting the Basic Law beyond the local courts while binding the local courts to make decisions,” Lai says.

“While Beijing interfered with Hong Kong’s judicial independence under each administration, what makes the difference is the degree of how the local administration applies or interprets the draconian laws,” he adds.

According to Lai, while sedition laws existed in Hong Kong even before its handover back to China in 1997, Lam’s administration is more eager to use them compared to previous administrations in Hong Kong.

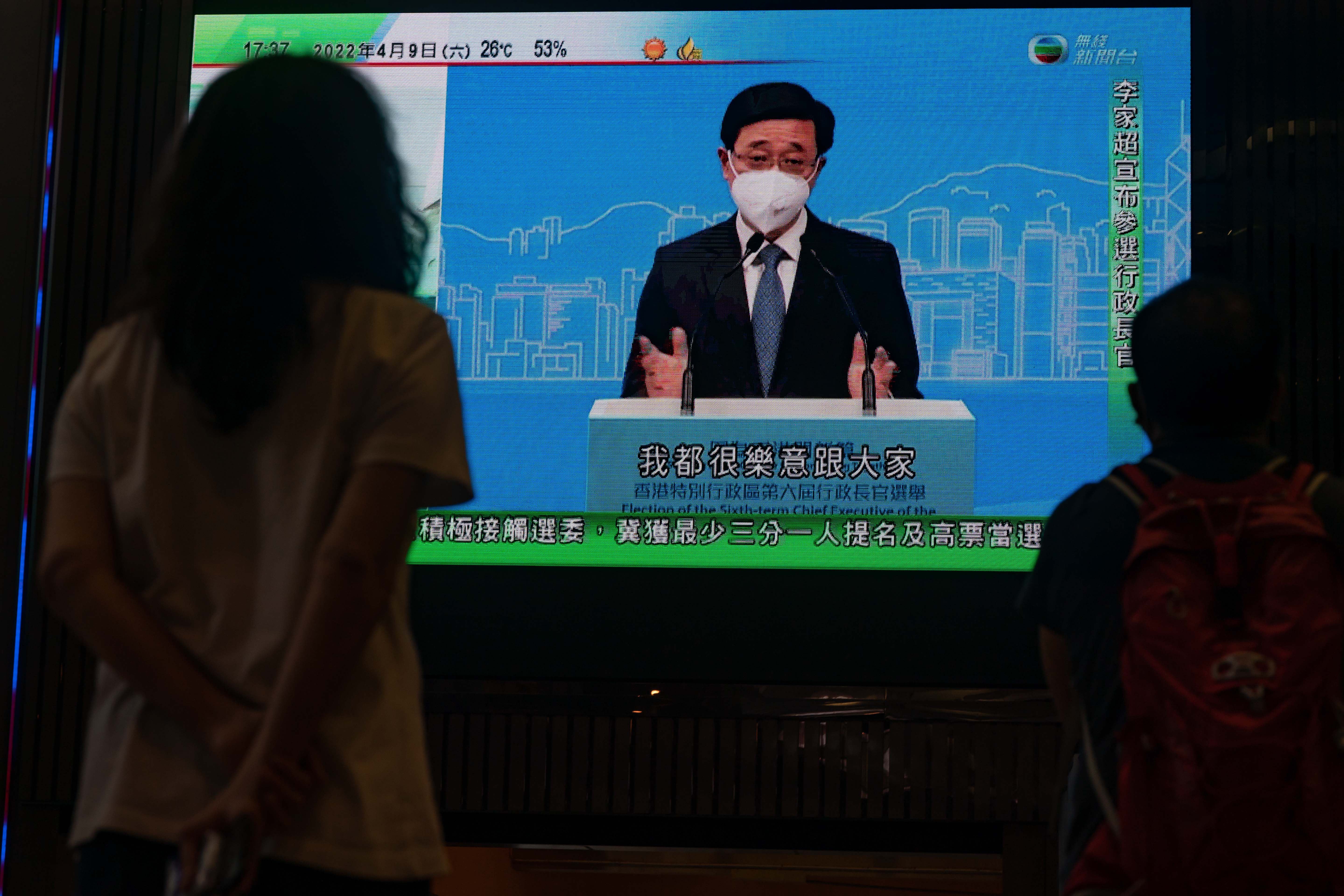

AfterLam announced last week that she would not bid for a second term, former chief secretary John Lee was viewed by many as the frontrunner in the upcoming election on 8 May. After Beijing approved his resignation from the role, Lee, a former police officer, formally declared his candidacy on the weekend.

In an online news conference, Lee said a government under his leadership would safeguard the rule of law and the “one country, two systems” framework that has allowed Hong Kong to maintain a level of autonomy since returning to China in 1997.

“This decision is made out of my loyalty to my country, my love for Hong Kong, and my sense of duty to the people,” he says.

As the first candidate for chief executive from Hong Kong’s law and order apparatus, some experts think this suggests that the Chinese government is going to prioritise national security and the security of its own regime over the next five years.

“A possible leadership under John Lee is going to create a lot of concerns for Hong Kong’s civil society,” Nachman says.

“This is going to be the first chief executive in the post-NSL era, and I think the responsibility and expectations from Beijing are going to be much heavier than they were before.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments