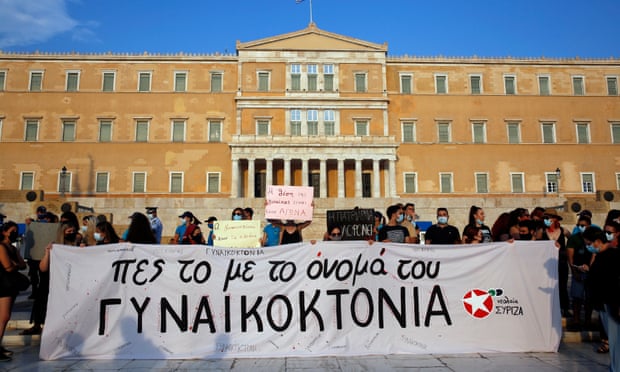

‘Not one more murder’: Greek women demand legal change to stop spate of femicides

Campaigners say sexism in Greece extends to the criminal justice system and that attitudes must change to prevent violence against women, writes Moira Lavelle in Athens

When Nektaria was killed by her ex-husband last month in Crete, she became the 13th victim of femicide in Greece so far in 2021 - a chilling figure that has rocked the country.

Reports of domestic violence have soared this year while brutal killings of women - happening at the rate of one a month - have dominated Greek media coverage and raised questions about the police’s response as well as the workings of the country’s laborious legal system.

But for Zambia Lazanaki, a preschool teacher in Crete, Nektaria was not just a statistic, headline, or talking point.

“She was part of my childhood,” she told The Independent, recalling how they had grown up in neighbouring villages and attended the same school.

She attended the funeral of 48-year-old Nektaria - whose full name has been withheld by law enforcement - at the end of October.

After her death, Nektaria’s friends reported that her ex-husband Yiannis Marakis had been abusive for years, but that the victim’s reports to the police led nowhere.

A cousin of the perpetrator claimed the murder was likely caused by jealousy after their divorce. Marakis, 54, pleaded guilty to manslaughter this month and is currently in prison awaiting trial.

“Something is happening in our society,” Lazanaki added. “Why can some men not handle a no from a woman? No woman is the property of any man. No woman belongs to anyone.”

Gender-based violence has long been endemic in Greece. Yet the increase in reports and cases since the start of the coronavirus pandemic, as well as the country’s growing #MeToo movement, have brought the issue to the fore.

Finally, women are talking ... many are raising their voice

Lawyers, counselors and campaigners say it is high-time, but that updating the country’s penal code, improving the criminal justice system, and ultimately changing the attitudes of both the public and authorities are essential if women are to be safe from violence.

“In Greece unfortunately we have a very strong tradition of patriarchal mentality,” said Maria Stratigaki, a social policy professor at Athens’ Panteion University.

“Gender inequality creates a context where gender-based violence is performed.”

Greece is the worst ranked EU country in the Gender Equality Index and has been for a decade, due to vast gender disparities in work, caregiving and positions of power, as well as high rates of violence against women. There were nine femicides last year, and eight in 2019.

For the past ten years government and police data showed steady year-on-year rises in reports of domestic violence.

Then, during March and April 2020 - when a national lockdown was imposed in Greece - there was a 227 per cent spike in the number of calls made to the country’s domestic violence and counselling centres compared to the preceding two months.

Nopi Sidiropoulou, a psychologist working at one of these centres, said the constant coverage of femicides in the Greek media this year had put her and her colleagues on high alert.

“We find ourselves making more safety plans,” she said. “Women are scared but more willing to talk about it.”

Greece only launched such services a decade ago but now has 43 counseling centers and 19 shelters nationwide, as well as a 24/7 helpline that offers psychological support and advice.

Maria Syrengela, Deputy Minister of Labor and Social Affairs, said the rise in calls partially reflected increased violence due to people being trapped inside with their abusers.

But she believed it was mainly due to more women being willing to speak out following a government awareness raising campaign last year, and the after-effects of the Greek #MeToo movement.

“Finally women are talking. (They) are not afraid to talk about their problems ... in the past that was a taboo for Greek society,” Syrengela said.

“Now with the Greek #MeToo movement, many women are trying to talk, many women are raising their voice,” Syrengela added.

When Olympic sailing champion Sofia Bekatorou opened up at the start of the year about being sexually assaulted by a sports official as a 21-year-old, her account spurred a cascade of #MeToo revelations after years of silence - especially in the arts and entertainment sectors.

Yet lawyer and campaigner Niki Roditi said many women are discouraged by police from filing reports or pressing charges, and that officers do not always pursue cases even when emergency calls are made.

A poll by market research company ProRata in January found that 70% of 1,115 Greek women surveyed had been victims of sexual harassment and abuse, and that 90% of those did not believe they could get any legal redress.

“It cannot be that a woman goes to the police to accuse her partner and they say to her: ‘Come on love, don’t file for charges now because you will enrage him more or you will enrage your children’,” said Roditi, the head of Medusa Survivor - an organisation in Chalkida that supports victims of domestic violence and sexual abuse.

“After that she will return home and he will kill her.”

Activists point to at least two femicides this year where they thought the police’s response was inadequate.

In one case, Konstantina Tsapa had applied for a restraining order and asked for police protection from her husband. Neither request was granted and the 28-year-old was stabbed to death in her village in Thessaly in May - the third femicide of 2021.

In the case of Anisa, whose name has been withheld due to an ongoing legal case, neighbours called the police in July when they heard yelling from her apartment in Athens, where she lived with her husband. Police drove to the building but did not leave their car.

Just weeks later, she was also killed with a knife, marking Greece’s seventh femicide this year.

The husbands in both cases have been charged with murder and are now awaiting trial.

The Hellenic Police told The Independent that their response to reports of domestic violence is determined on a case-by-case basis. A spokesperson said the focus was on protecting victims, investigating crimes and bringing alleged perpetrators to justice.

They said there is a new anti-domestic violence department within the Hellenic Police that has 73 offices nationwide.

Even when domestic violence is reported, few cases reach court and even fewer result in convictions.

In 2019, about 4,097 men were prosecuted for carrying out a criminal act against a member of their family, which covers domestic violence. Less than a third were convicted.

We know what happens every day in the patriarchy

Ioanna Stentoumi, an attorney who specializes in criminal and family law, said women faced various barriers when seeking justice.

In cases of physical violence or rape, victims who report it must undergo a forensic exam but regularly have to wait for several days because the relevant health professionals tend to only be located in big cities and do not work on weekends.

“I had a case for example with a rape which happened on a Saturday and we couldn’t find the forensic officer” said Stentoumi.“ Then in this case the victim would have to stay with the blood and everything until Monday or Tuesday.”

Furthermore, verbal and psychological abuse are almost impossible to prove in a Greek court, she said. Instead, during court proceedings - which can last several years - women often face questions about whether they were a good wife or partner, and if they provoked the abuser.

The legal system has made some positive changes recently.

Last month, Greece’s Bar Association set up a committee of legal experts to submit proposals for dealing with physical, psychological and sexual abuse in court.

And Athens’ Supreme Court prosecutor this month ordered judges to fast-track cases of domestic violence so that suspects could be arrested and tried quicker.

Several advocates including Stentoumi have called for femicide to be included in Greek’s penal code to help end a culture of impunity around violence against women.

The penal code currently allows homicide sentences to be reduced if the perpetrator was provoked or enraged - which in Greek refers to someone acting while in a “boiling mental” state and is often called a “crime of passion.”

“The truth is the abusers who end up killing their wives usually try to use this excuse,” said Stentoumi.

The inclusion of femicide could stop many men from using the defence of jealousy or rage in court, campaigners and feminist groups say.

“We don’t believe the problem will be solved with a change to the legal code, but it is a first step,” said Olympia Gaitanidi, a member of the feminist collective Medouses based in the city of Larissa.

“If there is no name for the problem, we cannot begin to solve it.”

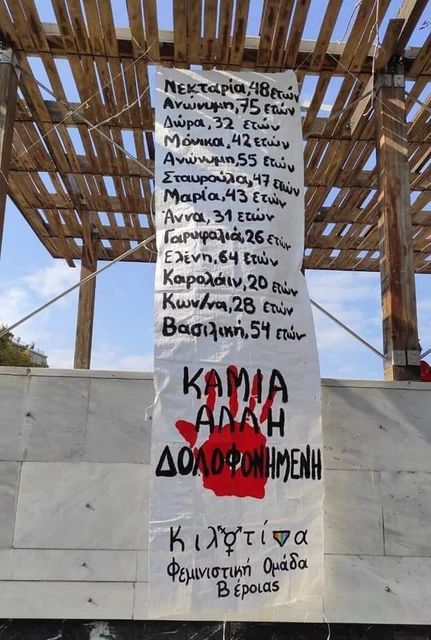

Ahead of a late October demonstration by another feminist collective - Kilotina - in the northern town of Veria, the campaigners made a banner featuring a red handprint, with the slogan ‘Not one more murdered’, and the names and ages of twelve women killed by men in Greece in 2021.

As they finished the banner, collective member Kalliopi Machailidou said the group decided to leave space at the top of the banner, fearing another femicide in the near future.

“It was like we knew it, and not because we can predict the future, but because we know what happens every day in the patriarchy,” she said.

On 29 October, the collective added a 13th name: “Nektaria, 48-years-old.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments