‘Our ship shuddered each time it was hit’: How more than 330,000 soldiers were evacuated from Dunkirk in ‘miracle’ operation

Kim Sengupta speaks to one of the last survivors of Dunkirk about the evacuation of Allied troops on 26 May 1940 that came close to disaster

The Luftwaffe started bombing while Alf and Tom White were in a convoy of trucks at Dunkirk. One of the trucks, packed with ammunition, caught fire: the two brothers and the other British soldiers scrambled to get away as the explosions spread around them.

They were directed by a military policeman to the beach where the evacuation of the stranded troops was underway. The scene was chaotic, with deafening noise, sand sprayed up by shells and ferocious air battles going on overhead.

“The ammunition truck was one of the ones in front of us, not very far away when it got hit. All hell broke loose. A redcap told us to head for the beach, there were so many people there, really packed,” Alf White recalls. “Tom and I had got separated in all the confusion. I thought it best not to hang around at the beach with all that was going on there and headed to the docks. I ran into Tom and some others there.”

The brothers joined the soldier on one of the rescue ships, an Isle of Man steamer. “The captain told us to get down below, but to make sure we stayed on just one side because the Germans had a shore battery on the other side. And sure enough the guns opened up. Our ship got hit four or five times, it shuddered each time it was hit, I didn’t know whether if it was going to stay up,” he recalls.

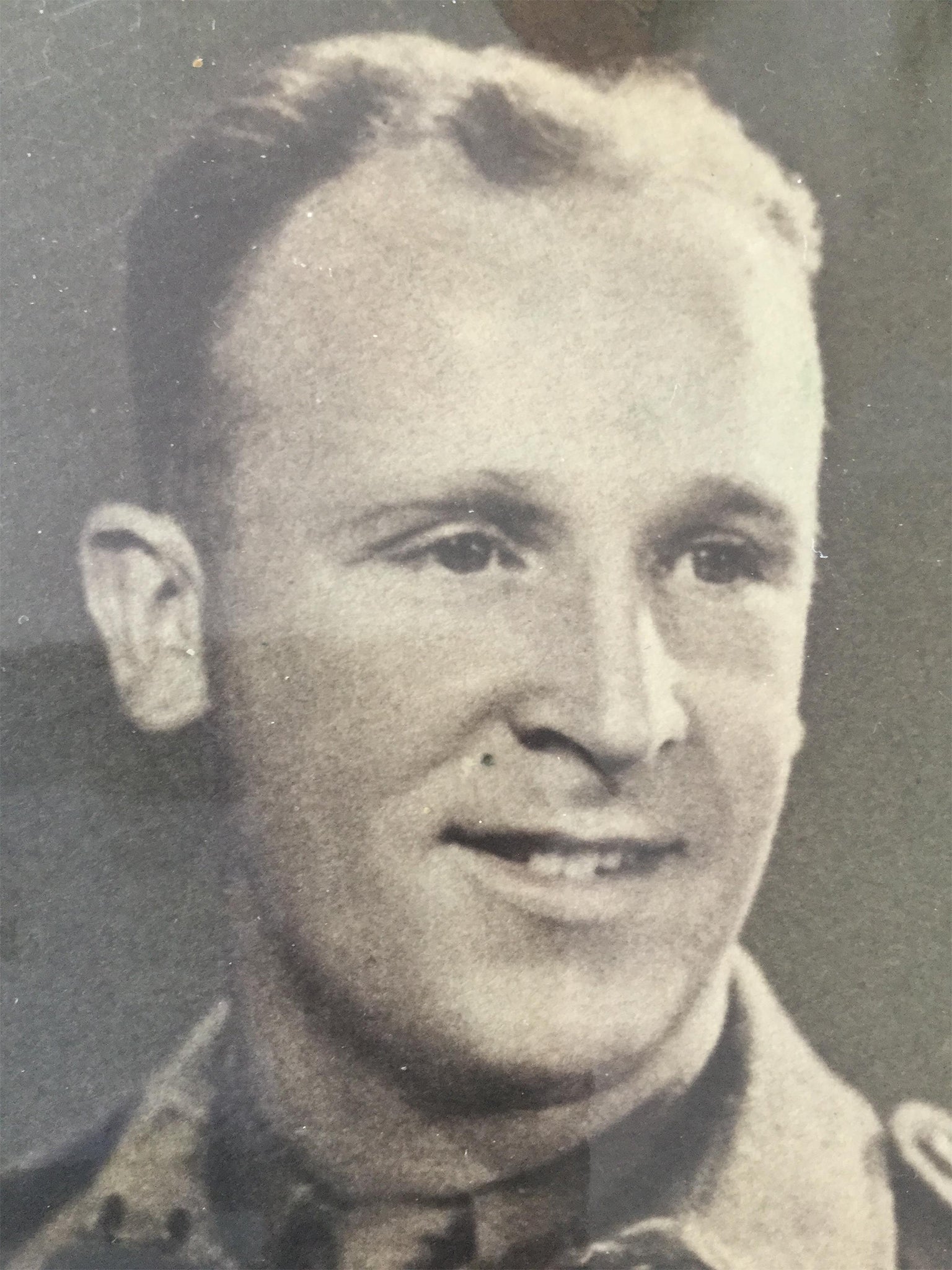

Alf, now 98 years old, speaks The Independent from his home in Merseyside. He is one of the last few survivors still around from Dunkirk. That was just the beginning of six years of war for him. Five years ago he was awarded the Legion d’honneur by the French government, the country’s highest military accolade. Tom was decorated for bravery in north Africa.

“Some of those who were on top deck died. I think around a dozen altogether. Quite a few were injured, including some down below, where we had gone. The firing went on for a long time. We sort of limped into Dover and they led out the dead and some of the seriously injured on benches. They were only young, it was a very sad sight” he says.

Alf was just 17 years old himself. He should not have even been at Dunkirk. But there had been a mix-up over his date of birth, which was recorded as 1920 instead of 1922 as it should have been. He and Tom had joined the Territorial Army in 1939 and were called up for the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) being sent to France as German forces invaded. His real age was discovered by an officer, but Alf did not want to leave, and the army kept him on.

The two brothers joined the 2nd Cavalry Division, which became the 1st Army Tank Brigade going out to France in March, following the declaration of war against Germany. After a few months of the “phoney war”, German forces invaded Belgium, Holland and France on 10 May. Eleven days later they had trapped the BEF, three French field armies and the remnant of Belgian forces in Dunkirk. The British commander, General Viscount Gort, decided the only realistic option was an urgent evacuation.

A total of 338,226 allied soldiers were evacuated, over eight days, by the Royal Navy and a civilian flotilla of around 850 vessels, the “Little Ships of Dunkirk”, as they became known. The BEF lost 68,000 soldiers in the French campaign and had to abandon almost all its tanks, much of its artillery, vehicle and equipment.

There were tough battles, we reached Benghazi at the end after three years of fighting

For Alf and Tom White, returning to England was just a short break. As the conflict spread, they were sent out to north Africa as part of the forces for Montgomery’s campaign against Rommel’s Afrika Korps. “There were tough battles, we reached Benghazi at the end after three years of fighting. But then a load of us got called back home as they were preparing for Europe and they were getting troops together,” he says.

He was part of the team which delivered fuel for the land operations following D-Day, a dangerous task. The oil had been sent in an extensive engineering operation codenamed Pluto, through pipelines laid under the same Channel waters used in the Dunkirk rescue.

Tom died twelve years ago at the age of 85. Alf retired from the National Coal Board as a shipping manager. He is living in lockdown at his home in Merseyside with his 92-year-old wife Audrey and son Steven.

The pandemic has meant that the “Little Ships of Dunkirk” would not be sailing from Ramsgate to Dunkirk, a voyage they have been making every five years since 1965 to commemorate the evacuation, Operation Dynamo.

Ships from the French and Belgian Navies were due to take part in the ceremonies. “It is extremely sad that we have had to make this decision to postpone Dunkirk 80. A huge amount of work has already gone into the arrangements both here and in Dunkirk, and many hours have been devoted to the preparation of the Little Ships for this commemorative crossing,” says Ian Gilbert, rear admiral of the Association of Dunkirk Little Ships (ADLS) .

However, a number of events have been planned and the Royal British Legion is keeping in contact with the veterans. It says: “The Royal British Legion honours the bravery and sacrifice of our Dunkirk heroes. We remember their service and sacrifice for hard-won peace, democracy and diversity. For nearly 100 years the legion has provided practical support when needed to the Armed Forces community, past and present.”

Analogies have been drawn repeatedly between the Second World War and the threat of coronavirus. There have been invocations of the Dunkirk and Blitz ”spirits”. On the 75th anniversary of VE Day, held in the shadow of the pandemic, Boris Johnson spoke of rising up to the fortitude of “quite simply the greatest generation of Britons who ever lived”.

Matt Hancock, the health secretary, declared: “Our generation has never been tested like this. Our grandparents were, during the Second World War, when our cities were bombed during the Blitz. Despite the pounding every night, the rationing, the loss of life, they pulled together in one gigantic national effort. Today our generation is facing its own test, fighting a very real and new disease. We must fight the disease to protect life.”

The human qualities of bravery, resilience and sacrifice made by servicemen and women, can be seen in those who are left like Private Alf White and Captain Tom Moore, who raised £32m for the NHS through his charity walk. Similarly, we know of the fortitude of the civilians as cities burned with air raids and hardship of food shortages endured.

But is it right to draw such parallels between the coronavirus and the Second World War? Sweeping changes took place in the world after the war, with the old imperial powers, such as Britain and France, emerging poorer and facing the process of losing their colonies. The US and the Soviet Union were the new superpowers and the Cold War began.

The post-contagion world will also see changes, with the likelihood of a Cold War between China and the US and its allies. The UK, like other countries, will be considerably poorer. But the course of the pandemic will turn; it will not, we now know unless there is a cataclysmic reverse, be an existential struggle.

Dunkirk, by itself, did not change the course of the Second World War. But what happened there had huge strategic and political consequences. Numbers were a key factor in Dunkirk as they are now with Covid-19.

At the beginning of the evacuation, the estimate in London was that only between 30,000 and 50,000 of the force would be evacuated. On 28 May Winston Churchill, who had only recently become prime minister, told cabinet members that getting 100,000 away would be a “magnificent” achievement: When the total at the end reached one-third of a million, Churchill proclaimed “the whole root and core and brain of the British Army” had been saved.

A little later he would also declare: “Let us brace ourselves to our duties, and so bear ourselves, that if the British Empire and its Commonwealth last for a thousand years, men will still say ‘this was their finest hour’.” The empire of a thousand years was not to be, just as Hitler’s promise of a “Thousand Years’ Reich” did not come to pass. But the “finest hour” speech became part of the lexicon of Britain’s War.

Faced with what seemed like an impending disaster at Dunkirk, the “appeasement” debate of the 1930s was being rehashed with calls for negotiations with Hitler. One idea was asking Mussolini to act as an intermediary: the calls for an accommodation with Germany ended with the successful rescue mission.

A failure of the evacuation, with the massive British and allied force put out of action, would also have made it difficult for Roosevelt to rally public opinion in the US against the Nazis in the face of fierce opposition from isolationists and campaigning by openly pro-Nazi groups like the German-American Bund. The fact that the troops had lived to fight another day strengthened the president’s hand and eased the path for the lend-lease programme for Britain until the US joined the war following Pearl Harbour.

One of the key questions about Dunkirk is: why did the Germans wait for three days before launching their attack on the trapped forces? The relative respite was crucial in organising a rearguard action as well as the rescue for the allies.

This remains an issue of debate among historians. One theory is that Hitler, as he had said on many occasions, did not want to prolong a war with Britain. In one of his last statements before he shot himself in his bunker in April 1945, he said he gave the British a “sporting chance” to escape in order to try and persuade London to come to an agreement.

But there are counter-arguments that it was simply a military miscalculation on the Fuhrer’s part. In any event, on 24 May he ordered the Panzer divisions who had driven back the allies to halt, and delegated the Luftwaffe to finish the job. Hitler rescinded that order on the afternoon of 26 May, but by then the allies had formed a defensive shield and the evacuation flotilla had been organised.

The Germans presented the rescue as a great retreat. On 5 June Hitler said in a speech: “Dunkirk has fallen! 40,000 French and English troops are all that remains of the formerly great armies; immeasurable quantities of material has been captured. The greatest battle in the history of the world has come to an end.”

Others too thought Germany was on a victory roll. Mussolini joined Hitler in the Axis pact after the fall of France. It was Italian and German troops who the White brothers and their comrades fought in north Africa. The same victories at the time gave Hitler and the German general staff the sense of great confidence which led to the invasion of Russia, an invasion which ended in defeat and disaster.

Eighty years on there is a tendency among some politicians in this country to be triumphalist about the war. The language has also been used at times in regards to coronavirus, such as Boris Johnson’s claim that the UK will have a “world-beating” system to test, track and trace for the virus, while the reality has left the country with the highest death rate in Europe.

But what marks most of those who actually fought in the war is their modesty, appreciation of the value of life, and great appreciation of those who are fighting to save lives in the contagion.

Thus the recently knighted John Moore wanted to stress: “Doctors and the nurses, they’re all on the front line, they are the heroes, and all of us have to supply them and keep them going. I’ve always been an optimist, I do believe that the future is going to be much better.”

Legion d’honneur holder Alf is also full of praise for those in the frontline against the pandemic. He speaks quietly of missing his brother and comrades who had gone in the war and in later years, but he is “very glad I am still here with my wonderful wife and children”. He, too, is looking forward to the future. His son Steven jokes the discussion is whether his 100th birthday should be on the real day, or the one that Army gave him sending him to Dunkirk.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments