Coronavirus: Warning of global protest ‘surge’ as pandemic threatens mass social unrest in dozens of nations

Africa, Latin America and the Middle East to be hardest hit by wave of political discontent amid looming hunger and unemployment, writes Borzou Daragahi

Millions of jobless and hungry people, enraged by the rising gap between rich and poor and corruption among their political elites, are set to challenge governments as the fallout of the coronavirus pandemic unfolds, according to development agencies, scholars and risk-management experts.

Dozens of countries around the world could experience calamitous and potentially violent protests in the coming months as a result of Covid-19 shutdowns and a global recession.

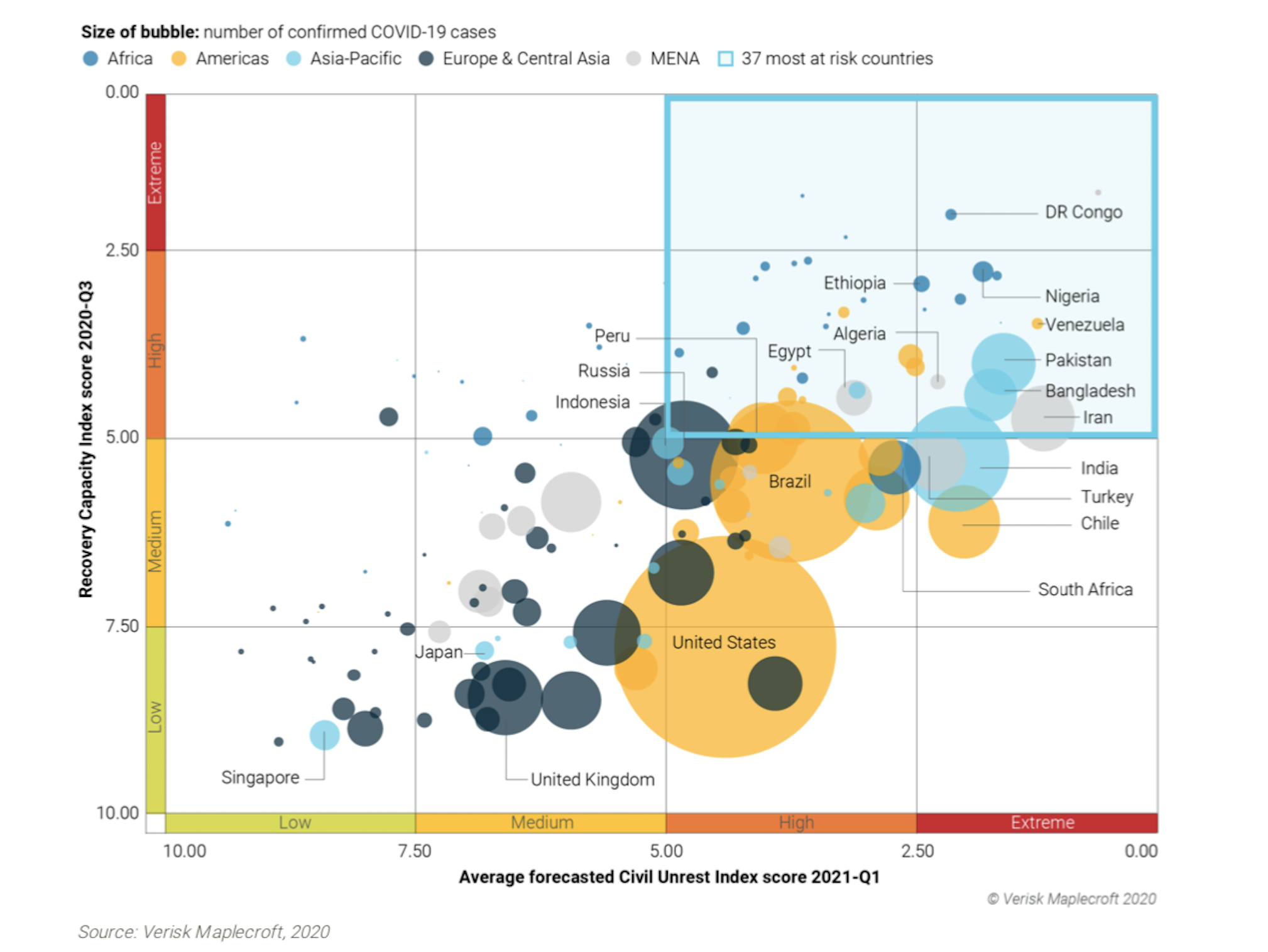

“As the economic fallout from Covid-19 mounts, protests in emerging and frontier markets are set to swell with millions of newly unemployed, underpaid and underfed citizens, posing a risk to domestic stability with few parallels in recent decades,” according to Verisk Maplecroft, a London-based risk management firm which issued a report on Friday listing 37 countries at risk of potentially catastrophic civil unrest in the coming months.

“We’re looking specifically at frontier and emerging markets but the trends are global,” Verisk Maplecroft analyst Miha Hribernik, author of the report, said in an interview. “Everyone can kind of feel it. The world is becoming very unstable.”

The hardest-hit nations will be sub-Saharan African and Latin American countries, including Nigeria, Democratic Republic of Congo, Ethiopia, Venezuela and Peru. But countries across the Middle East and Asia are also suffering sharp economic declines that could lead to social unrest and political instability by the end of the year.

Even the United States is in trouble, with worries that political polarisation ahead of a crucial presidential election in November and an economic crisis that has led to long food lines could ignite further unrest.

In the Middle East, the International Monetary Fund recently lowered its already dire projections, predicting economies will shrink on average 4.7 per cent in 2020. Per capita annual income in the region is predicted to drop from $2,900 to $2,000.

“Lasting labour market scars, together with worsening poverty and inequality, could create stability challenges for governments in the region, particularly considering the high level of unemployment in some countries,” said a report issued by the global lending agency this week. “In addition, social unrest could be rekindled as lockdown measures are lifted.”

In a press briefing on Monday, Jihad Azour, director of the IMF’s Middle East and Central Asia division, painted a bleak picture for the months ahead.

“The period ahead will be marked by high uncertainty amid the unclear shape and the speed of the global recovery,” he told reporters. “The risks of a second-round pandemic with more protracted impact are elevated.”

Economic pain is not the sole factor driving potential unrest. Most of the countries likely to experience instability already face high levels of political polarisation and anger with the government. Protests over economic troubles and ossified political leadership in developing nations declined in March with the lockdowns. But already protests in vulnerable nations have returned to near pre-pandemic levels.

“As lockdowns ease, people have started to protest again,” said Mr Hribernik. “People are protesting lockdowns, unhappy that they’ve lost a job. There are protests over pre-existing grievances. And there are protests which are about overlapping issues.”

Among the countries identified at the highest risk are Iran and Algeria, which both have a low ability to recover from the pandemic and a high degree of “pre-existing grievances” that create a general climate of political discontent. They tend to be countries with both high internet connectivity and susceptibility to natural disasters or terrorism. Opposition political groups have already begun to call for protests in several countries.

“We are seeing upticks of some social movements, especially with countries reopening,” said Mr Azour.

Indicators in other countries such as Brazil, India, Russia, and South Africa also suggest impending trouble in nations that only years ago were identified as rapidly growing havens for investors seeking profits and workers seeking to enter the middle class.

In vulnerable nations such as Nigeria, growing food insecurity is causing major crises. In Lagos, food prices have jumped 50 per cent in recent months. “This volatile climate only requires a spark to set off major unrest,” said the Verisk Maplecroft report.

One paper studying the effects of coronavirus lockdown measures in 24 African countries showed that every 10 per cent increase in food prices resulted in an increase of 0.7 per cent in violence. “We find that the probability of experiencing riots, violence against civilians, food-related conflicts and food looting has increased since lockdowns,” said the report by Queen Mary University of London scholar Roxana Gutierrez-Romero.

Both Ms Gutierrez-Romero and Verisk Maplecroft used data gleaned from the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project, which tracks civil and military unrest around the world.

In Latin America, politically volatile Venezuela remains the most sensitive to post-coronavirus shocks. But Peru, Chile, and Argentina are also at risk.

The US has emerged on Verisk Maplecroft’s list as the 48th-riskiest nation worldwide, with civil unrest spiking in the wake of the violent police action against Black Lives Matter protests and the botched handling of the pandemic by the administration of Donald Trump.

The unrest could have far-reaching international consequences. Economic ruin in developing countries such as Brazil and Indonesia once considered the engines of growth could trigger and deepen woes in developing countries. A recent study by Australian scholars warned that the pandemic, though it has for now meant closed borders and constrained travel, could ultimately hasten migrant flows from poorer countries to the richer West.

Some analysts have warned that Europe, too, could face major political unrest as a result of the pandemic.

But most economists agree that even the poorer eastern European and Balkan countries have strong enough healthcare and social welfare institutions to help them pull through.

“As bad as things are, those countries with developed economies are relatively well-equipped to recover,” said Mr Hribernik.

Meanwhile joblessness, poverty, travel bans, and reduced relief operations hurt those most in the global south, especially in countries where huge numbers of people are dependent on the informal economy and with limited access to state subsistence programmes.

“The pandemic has been especially harmful to those living in fragile states,” said a report this month by the Institute for Economics and Peace, a think tank based in Australia. “Without support, these fragile countries will struggle to recover, thereby creating the conditions for future increases in civil conflict.”

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments